Woodville Historical Museum

Woodville Historical Museum

Inside the Museum

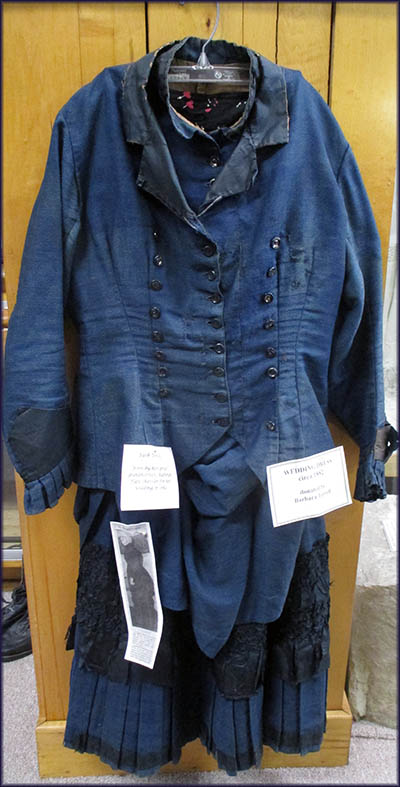

Wedding Dress from About 1882

The Graphtype machine produced the plates for printing.

Upon this sofa are a number of artifacts.

Baby Buggy from the Latter Part of the 19th Century

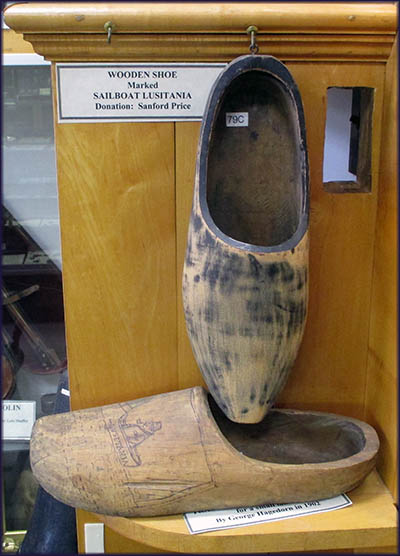

Wood Shoes from the Sailboat Lusitania

This camera was used by the Toledo police in the 1920s and 1930s and supposedly snapped a mugshot of gangster John Dillinger.

This clock was created by the Pheils Universal Clock Company of Toledo, Ohio.

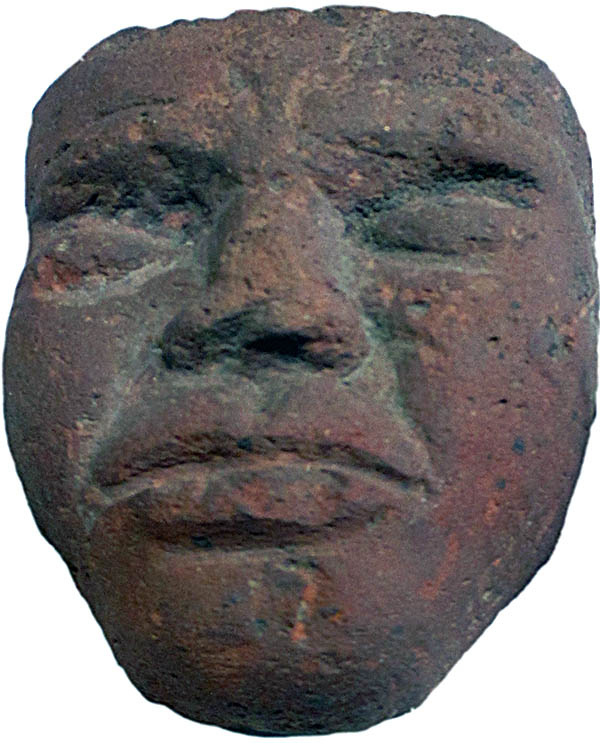

Ohio Native Americans made this mask, although which group is unknown.

The one-room Woodville Historical Museum is filled with so many locally-collected artifacts, a volunteer remarked that a bigger building is needed to house it all. Often when you display this much in such a small area, it looks cluttered and confused, resembling an antique mall. But whoever organized this museum’s layout is a genius. It’s well-organized with no feeling of untidiness.

The quality of what is on display is impressive. There is, for example, a well-crafted terracotta Native American mask. According to the scant information about it in the April 1965 issue of Ohio Archeologist, it’s either an effigy or a death mask. No mention of which people created it was made. It was unearthed by a Wood County farmer in 1884 about half a mile from the village of Risingsun.

The quality of what is on display is impressive. There is, for example, a well-crafted terracotta Native American mask. According to the scant information about it in the April 1965 issue of Ohio Archeologist, it’s either an effigy or a death mask. No mention of which people created it was made. It was unearthed by a Wood County farmer in 1884 about half a mile from the village of Risingsun.

The first Americans who settled where Woodville now stands found themselves in the middle of the Great Black Swamp. Swamps aren’t healthy places and this one was no exception. While ecologically important, they are filled with parasites carrying diseases to which humans and most livestock are susceptible. During the wet season, water covered much of the region. When it receded, it left behind a spongy soil.

Land-hungry Americans from the East who settled here drained the swamp to make it a more habitable environment for themselves. Most of these early pioneers came from Pennsylvania and New York and were attracted to the region because the land was so cheap. It was, after all, a swamp. Smart settlers moved here during the winter when the ground was frozen.

Woodville was first platted (that is, surveyed and divided into lots) in 1836 by Ephraim Wood, Jr. of Vermont and G.H. Price of New York. A second plat was made in 1838 by Amos Pratt and Daniel Hubbell, although they didn’t get around to filing theirs until 1843. The town was probably named for Wood, who built a tavern in which Woodville Township’s first election was held in 1840. A petition to incorporate Woodville as a village was submitted to the State of Ohio on August 12, 1884.

Land-hungry Americans from the East who settled here drained the swamp to make it a more habitable environment for themselves. Most of these early pioneers came from Pennsylvania and New York and were attracted to the region because the land was so cheap. It was, after all, a swamp. Smart settlers moved here during the winter when the ground was frozen.

Woodville was first platted (that is, surveyed and divided into lots) in 1836 by Ephraim Wood, Jr. of Vermont and G.H. Price of New York. A second plat was made in 1838 by Amos Pratt and Daniel Hubbell, although they didn’t get around to filing theirs until 1843. The town was probably named for Wood, who built a tavern in which Woodville Township’s first election was held in 1840. A petition to incorporate Woodville as a village was submitted to the State of Ohio on August 12, 1884.

Woodville is in Sandusky County, which was named after the Sandusky River, this appellation being derived from the native name Tsaendosti (pronounced “San-doos-tee”). According an article by Basil Meek that appeared in the Ohio History Journal, the word meant “it is cold [,] fresh (water).” Sandusky County was originally much larger than it is today. A museum information sign reported that it once “stretched all the way to Lake Erie” and included “the land that is now Ottawa County and part of what is now Lucas County.” The county seat, Fremont, was originally named Croghanville in honor of Colonel George Croghan, who successfully defended Fort Stephenson against the British and their Native American allies when they attacked it in August 1813. Croghanville was renamed Lower Sandusky in 1829, then Fremont in 1848. The final name was suggested by its most famous resident, Rutherford B. Hayes, who later became a U.S. president.

The east-west Maumee & Western Road bisected Woodville. The State of Ohio started construction on this road in 1824 and completed it in 1827. According to an Ohio Historical Marker sign, it was “the first road to traverse Sandusky County through the Black Swamp.… [It] connected Lower Sandusky (Fremont) and Perrysburg with Woodville.” At 120 feet in width, for much of the year it was so muddy that traveling a mile a day was considered making good time. In 1838, the state appropriated $40,000 to pay for additional drainage work and apply stone to the road surface. At this point it became a turnpike, though it was made free once more in 1888. It is now U.S. Route 20.

The east-west Maumee & Western Road bisected Woodville. The State of Ohio started construction on this road in 1824 and completed it in 1827. According to an Ohio Historical Marker sign, it was “the first road to traverse Sandusky County through the Black Swamp.… [It] connected Lower Sandusky (Fremont) and Perrysburg with Woodville.” At 120 feet in width, for much of the year it was so muddy that traveling a mile a day was considered making good time. In 1838, the state appropriated $40,000 to pay for additional drainage work and apply stone to the road surface. At this point it became a turnpike, though it was made free once more in 1888. It is now U.S. Route 20.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Woodville’s population could not only use this road, they also had the option of using the electric interurban train lines that connected their village to the wider world. At first these interurbans (that is, railroads the connected different towns) consisted of relatively short lines. These were bought by and integrated into the Lake Shore and Electric Railway (LSR), a system that stretched between Toledo and Cleveland. In Woodville, the last interurban cars stopped running on May 15, 1938. Bus routes replaced it, and some of these continued to run through Woodville until the 1970s.

A person passing through the village and the surrounding area would never guess the region was once the center of a massive oil boom that burst onto the scene in 1887. Although most of Sandusky County’s oil wells produced only modest amounts of oil, T.E and J.W. Kirkbridge struck it rich on November 15, 1894, at Benjamin Jones’ farm. Their well briefly produced the second largest amount of oil then found in the United States.

Although the oil boom brought much prosperity to Woodville, it did have a major downside. Like many of Ohio’s earliest settlements, Woodville was built along a river, the Portage in this case. For many years it was a good source for food, but waste oil poured into it (mainly from Wood County) killed off most of its fish and sickened any livestock that drank from it. The river also had a habit of catching on fire. People complained, but in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, local, state and federal governments weren’t in the business of doing anything about it.

A person passing through the village and the surrounding area would never guess the region was once the center of a massive oil boom that burst onto the scene in 1887. Although most of Sandusky County’s oil wells produced only modest amounts of oil, T.E and J.W. Kirkbridge struck it rich on November 15, 1894, at Benjamin Jones’ farm. Their well briefly produced the second largest amount of oil then found in the United States.

Although the oil boom brought much prosperity to Woodville, it did have a major downside. Like many of Ohio’s earliest settlements, Woodville was built along a river, the Portage in this case. For many years it was a good source for food, but waste oil poured into it (mainly from Wood County) killed off most of its fish and sickened any livestock that drank from it. The river also had a habit of catching on fire. People complained, but in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, local, state and federal governments weren’t in the business of doing anything about it.

Oil booms are by their nature short-lived, and this one died out around 1905. Fortunately, the village had another, longer lasting natural resource it could readily exploit: lime. Today there are several companies operating near the village extracting and selling this mineral, which has so many uses, it’s likely demand for it will remain for a long time to come. No doubt the nitroglycerine cylinder on display at the museum came from one of these quarries.

During my visit, a volunteer pointed to a wedding dress with a wasp-thin waistline and informed my traveling companion and I that women in Victorian age had two ribs surgically removed so they could fit in such dresses. This is a myth. The only thing a Victorian woman who had her ribs removed would fit into afterward was a coffin. This was no routine surgery. Presuming one survived the initial operation, there was a good chance a deadly infection would set in and kill the patient.

Most of the museum’s collection of wedding dresses didn’t have wasp-thin wastes and were notably dark in color. This wasn’t unusual at the time. The tradition of a woman wearing white was supposedly started by Queen Victoria when she wore one to her 1840 wedding. Judging by the dates of the museum’s collection of wedding dresses, which are primarily from the 1870s and 1880s, the color white must’ve taken quite some time to catch on in the United States.

During my visit, a volunteer pointed to a wedding dress with a wasp-thin waistline and informed my traveling companion and I that women in Victorian age had two ribs surgically removed so they could fit in such dresses. This is a myth. The only thing a Victorian woman who had her ribs removed would fit into afterward was a coffin. This was no routine surgery. Presuming one survived the initial operation, there was a good chance a deadly infection would set in and kill the patient.

Most of the museum’s collection of wedding dresses didn’t have wasp-thin wastes and were notably dark in color. This wasn’t unusual at the time. The tradition of a woman wearing white was supposedly started by Queen Victoria when she wore one to her 1840 wedding. Judging by the dates of the museum’s collection of wedding dresses, which are primarily from the 1870s and 1880s, the color white must’ve taken quite some time to catch on in the United States.

Also in the museum’s collection are wooden shoes donated by Sanford Price. Although they tend to be associated with Europeans, they were also used by Americans. An article in the May 1918 issue of The Leather Manufacturer trade magazine, for example, reported that a shoe seller in Cincinnati had run this advertisement in the Cincinnati Enquirer: “Keep Your Feet Warm. All-wood shoes, and Wood-Soled Leather-Top Shoes and Boots, in all sizes, for men, women and children.” The article’s writer was surprised that there was enough demand to make it worth advertising wooden shoes.

An article in the April 1892 issue of Donahoe’s Magazine pointed out that wooden shoes were often worn by “persons who are employed in damp, sloppy places” such as tanneries. Women sometimes wore them on washing days. “Some wooden shoes,” the article went on to say, “are made to order in most elaborate style, being engraved or painted and made light in weight.” Among other places, a factory in Grand Rapids, Michigan, mass produced them. There was also a demand for wooden clogs, some of which were fancy and used by dancers. One of the pairs of wooden shoes on display in the museum came from the sailboat Lusitania, certainly a place was getting one’s feet wet wasn’t uncommon.

I’ve never been to an historical society museum that didn’t have at least one piano or organ or both, and in this respect the Woodville Historical Museum didn’t disappoint. It has one of each. Its piano is an upright Steinway, which I’m sure some collector would salivate over if he or she knew of its presence here. The organ is a small foot-pump type capable of six octaves. It was rescued by Paul Hammer and his friend, Bill Mercer, after Paul’s wife, Barbara, told them that her uncle had its pieces in his attic and planned to take it to the dump. Paul brought it to his barber shop where over the winter he and Bill reassembled and restored it to its former glory. They had no idea who the manufacturer was, and, because I have so many photos of organs posted in other travel logs, I didn’t bother to take a picture of this one while I was at the museum.

Speaking of pictures, the museum has a camera used by the Toledo police during the 1920s and 1930s that supposedly took a mugshot of John Dillinger. The closest Dillinger came to Toledo was Lima, where he languished in its jail until his confederates broke him out—killing the sheriff in the process. So unless the camera was at that time in the possession of the Lima jail, or the sheriff borrowed it from Toledo, it’s unlikely that it took the Dillinger’s photo.

An especially interesting piece is a clock designed by Isaac F. Pheils for which he was issued a patent on January 13, 1903. Made by the Pheils Universal Clock Company in Toledo, Ohio, it shows a wide variety of times from the northern hemisphere. It also displays railroad timetables for different time zones. It was found under a pile of coal in Woodville’s Keil Building.🕜

An article in the April 1892 issue of Donahoe’s Magazine pointed out that wooden shoes were often worn by “persons who are employed in damp, sloppy places” such as tanneries. Women sometimes wore them on washing days. “Some wooden shoes,” the article went on to say, “are made to order in most elaborate style, being engraved or painted and made light in weight.” Among other places, a factory in Grand Rapids, Michigan, mass produced them. There was also a demand for wooden clogs, some of which were fancy and used by dancers. One of the pairs of wooden shoes on display in the museum came from the sailboat Lusitania, certainly a place was getting one’s feet wet wasn’t uncommon.

I’ve never been to an historical society museum that didn’t have at least one piano or organ or both, and in this respect the Woodville Historical Museum didn’t disappoint. It has one of each. Its piano is an upright Steinway, which I’m sure some collector would salivate over if he or she knew of its presence here. The organ is a small foot-pump type capable of six octaves. It was rescued by Paul Hammer and his friend, Bill Mercer, after Paul’s wife, Barbara, told them that her uncle had its pieces in his attic and planned to take it to the dump. Paul brought it to his barber shop where over the winter he and Bill reassembled and restored it to its former glory. They had no idea who the manufacturer was, and, because I have so many photos of organs posted in other travel logs, I didn’t bother to take a picture of this one while I was at the museum.

Speaking of pictures, the museum has a camera used by the Toledo police during the 1920s and 1930s that supposedly took a mugshot of John Dillinger. The closest Dillinger came to Toledo was Lima, where he languished in its jail until his confederates broke him out—killing the sheriff in the process. So unless the camera was at that time in the possession of the Lima jail, or the sheriff borrowed it from Toledo, it’s unlikely that it took the Dillinger’s photo.

An especially interesting piece is a clock designed by Isaac F. Pheils for which he was issued a patent on January 13, 1903. Made by the Pheils Universal Clock Company in Toledo, Ohio, it shows a wide variety of times from the northern hemisphere. It also displays railroad timetables for different time zones. It was found under a pile of coal in Woodville’s Keil Building.🕜