Ukrainian Museum-Archives

Museum Exterior

Museum Interior

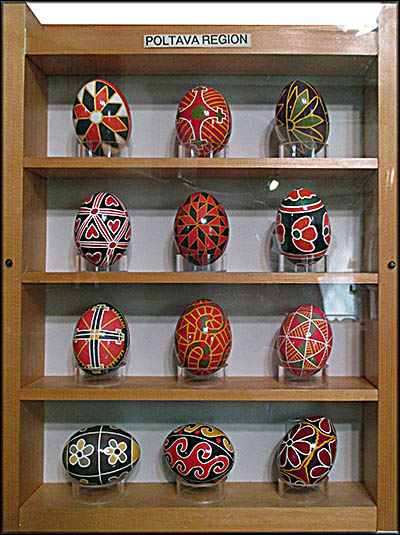

Decorative Eggs

Sometime in the early 1990s, my brother-in-law and I went to Brooklyn, Ohio, to buy some parts at a computer store. When I noticed a female worker had what I perceived to be a Russian accent, I asked her: “What part of Russia are you from?” To which she indignantly replied, “I am not Russian, and I am Ukrainian!” I didn’t know it at the time, but Cleveland and its suburbs have a significant number of Ukrainians who either recently arrived or are descendants of those who came in earlier generations.

Often when I visit a museum, I feel overwhelmed by the number of information signs it has. This forces me to pick and choose what to read lest I have to camp overnight to get through them all. The Ukrainian Museum-Archives has the opposite problem. It needs a whole lot more signs to guide visitors and give them some context as to just what is on display. That’s not to say that if you ask a staff member questions, you won’t get excellent, detailed answers.

On the first floor, one room contains Ukrainian cultural artifacts. Among these is a large collection of decorated eggs that are part of a Ukrainian tradition called pysanky. The shapes and symbols covering them aren’t arbitrary. Sunflowers, as an example, represent the sun’s warm rays. Trees are stand-ins for health and eternal youth. Storks are, not surprisingly, a fertility symbol, as are chickens. Shapes, too have, their meanings. A ribbon represents everlasting life. Suns and stars are for good fortune.

Upon climbing up the stairs to the second floor, you enter a wide hall. Along one side of it hang photos of Ukrainians who came to the United States. Information signs containing snippets of the oral history accounts they gave are in both Ukrainian and English. Their full recollections are in little booklets setting on a shelf below the display.

On the first floor, one room contains Ukrainian cultural artifacts. Among these is a large collection of decorated eggs that are part of a Ukrainian tradition called pysanky. The shapes and symbols covering them aren’t arbitrary. Sunflowers, as an example, represent the sun’s warm rays. Trees are stand-ins for health and eternal youth. Storks are, not surprisingly, a fertility symbol, as are chickens. Shapes, too have, their meanings. A ribbon represents everlasting life. Suns and stars are for good fortune.

Upon climbing up the stairs to the second floor, you enter a wide hall. Along one side of it hang photos of Ukrainians who came to the United States. Information signs containing snippets of the oral history accounts they gave are in both Ukrainian and English. Their full recollections are in little booklets setting on a shelf below the display.

One story was told by Eva Olijar. During World War II, she and her husband served in the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, a nationalist guerilla force that fought against Nazis, Soviets, and anyone else who opposed Ukrainian independence. After the war, Eva went underground because the Soviets were coming for her, but her effort to escape failed. At the time of her arrest, she had her child with her. The Soviets tried to get her to sign the child over to them, but she refused. She stayed in a gulag until 1956 when the U.S.S.R. let her go after a general amnesty forgiving political prisoners. Her husband, who’d made it America, managed to get her to the United States with help from the Red Cross.

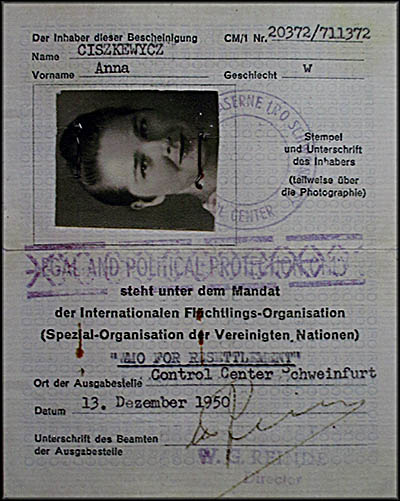

Nazi-issued ID for a Ukrainian Slave Laborer

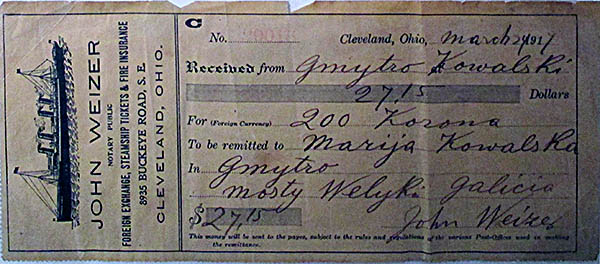

The first wave of Ukrainian immigrants to come to the United States arrived in the 1870s to escape poverty. In the 1880s, they started moving from the Atlantic coast into the American interior, and quite a few made their way to Ohio in general and Cleveland in particular. By 1900, an estimated 10,000 Ukrainians lived in Ohio. Most never intended to stay. They planned to earn enough to live comfortably upon their return home. The takeover of Russia by the Bolsheviks and the formation for the Soviet Union convinced many to stay put.

A few years ago I saw a brochure advertising the Ukrainian Museum-Archives, which is located in the Tremont neighborhood of Cleveland. I added it to a list of places I wanted to visit but never got round to going there. In light of the recent unjustified and reprehensible Russian invasion of Ukraine, I thought it an apt time to check it out. It’s located in a modest two-story house on a quiet Cleveland street alongside a park.

Cash-starved, it has a small, knowledgeable staff who curate a pretty spectacular collection of mostly donated items. There are works of art, for example, by the Ukrainian American artist Alexander Archipenko, the first person to create Cubist architectural works. The museum’s extensive archives include oral histories of those who came from Ukraine to the United States, recordings of programs from the Voice of America broadcast into Ukraine, thousands of post cards, posters, a multilingual library with over 20,000 books, and even a collection of phonograph records from the 1910s.

Cash-starved, it has a small, knowledgeable staff who curate a pretty spectacular collection of mostly donated items. There are works of art, for example, by the Ukrainian American artist Alexander Archipenko, the first person to create Cubist architectural works. The museum’s extensive archives include oral histories of those who came from Ukraine to the United States, recordings of programs from the Voice of America broadcast into Ukraine, thousands of post cards, posters, a multilingual library with over 20,000 books, and even a collection of phonograph records from the 1910s.

Alarmed that all these Eastern Europeans wouldn’t integrate into American society and adopt its culture, schools were opened to teach them English and American traditions. Like most first generation immigrants, they tended to form their own insular communities in which they practiced their culture and spoke their own language. To deal with discrimination, the Ukrainian community in Cleveland founded its own banks. In the years between World War I and II, its cultural activities broadened. It formed bands and choirs. Theater became important. Some Ukrainians went into showbusiness. Captain Jacques Babenko, a Cossack cavalryman who’d fought in the failed independence movement against the U.S.S.R. after World War I, came to America to escape the ire of the Bolsheviks. He joined a Cossack touring show, then made his way to Hollywood as a stunt rider in cowboy movies.

Steamship Ticket Used by a Ukrainian Immigrant

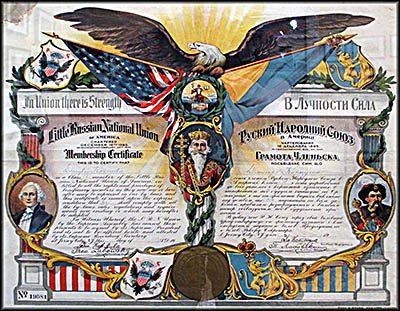

In Cleveland and its suburbs, most Ukrainians were Greek Orthodox or Roman Catholic, so they built a whole lot of churches, many of which still stand and are in use. In 1894, Ukrainian Americans formed the Little Russian National Association, a label serving as a nod to the fact that Russian Empire had its roots in Ukraine. It was set up to aid new Ukrainian immigrants. It later changed its name to the Ukrainian National Association, which still exists.

One of the upstairs rooms shows artifacts from Ukrainians forced by the Nazis to work as slave laborers in Germany. There are pictures of Nazi-issued IDs, and a patch that says, “OST” (east) that Ukrainian slave laborers had to wear to identify themselves. They were put into camps segregated by sex. Workers from the east such as the Ukrainians were treated especially bad. Both men and women were given the dirtiest and dangerous tasks. They worked in twelve hour shifts and had little leisure time.

After the war, many liberated Ukrainian slaves found themselves in American-run displaced persons (DP) camps. The museum has a section dedicated to tell their stories. One such person was Andrij Steciak and his wife, Anna. Sponsored by a Maryland farmer, in 1949 they came to America on the ship Marine Jumper, which arrived in Baltimore on June 24. Here Andrij and Anna departed. The farmer and his wife who’d sponsored Andrij picked them up in a “limousine.” Andrij, who recorded this in his diary, probably thought any large American car or truck was like a limo. Certain the farmers weren’t wealthy. They lived in a tiny house without electric amidst fields of corn and tobacco. Reaping the harvest by hand made Andrij’s arms hurt so bad he found he couldn’t sleep because of the pain. On September 25, he resolved to quit and find something better.

Behind the museum’s house is small building that contains a display of photos by Sasha Maslov that he took of Ukraine’s “railroad ladies”—women who serve as safety officers and traffic controllers along Ukraine’s railroads. These women live in small houses that stand along the tracks and spend long stretches of their days working. As a train passes by, they wave a yellow flag to indicate all is well ahead. One of the questions the artist asked is why despite near total automation of Ukraine’s railroads do they still need these women? According to an information sign, the answer is that the women are a “lighthouse. They are a symbol of certain things in this county [Ukraine] that don’t change, standing in the pres- ent [sic] as a defiant nod to the past.”

One of the upstairs rooms shows artifacts from Ukrainians forced by the Nazis to work as slave laborers in Germany. There are pictures of Nazi-issued IDs, and a patch that says, “OST” (east) that Ukrainian slave laborers had to wear to identify themselves. They were put into camps segregated by sex. Workers from the east such as the Ukrainians were treated especially bad. Both men and women were given the dirtiest and dangerous tasks. They worked in twelve hour shifts and had little leisure time.

After the war, many liberated Ukrainian slaves found themselves in American-run displaced persons (DP) camps. The museum has a section dedicated to tell their stories. One such person was Andrij Steciak and his wife, Anna. Sponsored by a Maryland farmer, in 1949 they came to America on the ship Marine Jumper, which arrived in Baltimore on June 24. Here Andrij and Anna departed. The farmer and his wife who’d sponsored Andrij picked them up in a “limousine.” Andrij, who recorded this in his diary, probably thought any large American car or truck was like a limo. Certain the farmers weren’t wealthy. They lived in a tiny house without electric amidst fields of corn and tobacco. Reaping the harvest by hand made Andrij’s arms hurt so bad he found he couldn’t sleep because of the pain. On September 25, he resolved to quit and find something better.

Behind the museum’s house is small building that contains a display of photos by Sasha Maslov that he took of Ukraine’s “railroad ladies”—women who serve as safety officers and traffic controllers along Ukraine’s railroads. These women live in small houses that stand along the tracks and spend long stretches of their days working. As a train passes by, they wave a yellow flag to indicate all is well ahead. One of the questions the artist asked is why despite near total automation of Ukraine’s railroads do they still need these women? According to an information sign, the answer is that the women are a “lighthouse. They are a symbol of certain things in this county [Ukraine] that don’t change, standing in the pres- ent [sic] as a defiant nod to the past.”

Photos from the "Railroad Ladies" Exhibit.

The photos are contemporary and for sale. While good—at least one had sold—I must admit I can’t imagine wanting one of them on display in my house. The photographer, Maslov, was born in 1984 in Krarkiv, Ukraine, where he worked in advertising until uprooting himself to New York City. The photos in the museum’s exhibit also appeared in the March 2021 issue of National Geographic.🕜

Ukrainians forced to labor in Germany had to wear badges like this to identify them as being from the "East."

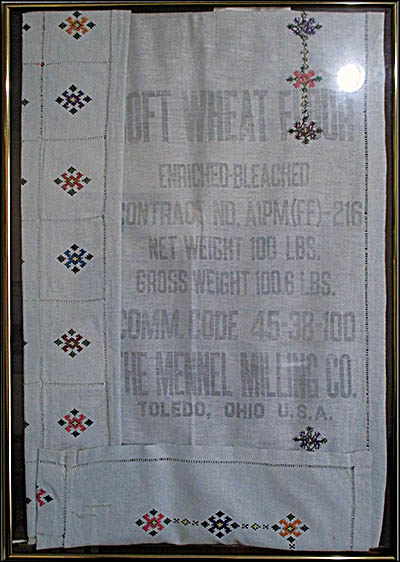

This former flour sack was embroidered by Maria Kowalysko, was repurposed as a table cloth. Kowalkysko was a displaced person who fled from the returning Soviet forces and wound up in a camp in Germany.

Displaced Person ID

"Ivan Franko"

Alexander Archipenko

Alexander Archipenko

This certificate was issued by the Little Russian National Union, an organization dedicated to helping Ukrainian immigrants arriving in the United States. It's now called the Ukrainian National Association.

Luggage used by Ukrainians escaping to the United States.

Out building that contains the "Railroad Ladies" exhibit. It's also where decorated eggs are made for sale in the gift shop.

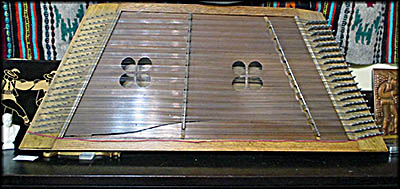

Tsymbaly