Spring Hill Historic Home

Spring Hill House Front

Spring Hill House Back

Basement

Parlor

Library

Visitors at Spring Hill Historic Home are given a tablet with an audio narrative about the house that focuses on the Underground Railroad. The audio leaves the listener ignorant of the house’s original inhabitants, Thomas and Charity Rotch. For that information I went to the excellent digitized collection of family papers found on the Massillon Public Library’s website. The house was built by Thomas, a member of the Society of Friends, or Quakers. Born in 1767, he worked for his family’s whaling and shipping company based out of New Bedford and Nantucket, Massachusetts. Two of its ships were involved with the Boston Tea Party.

On June 6, 1790, Rotch married Charity Rodman, a fellow Quaker and native of Newport, Rhode Island, who had been born there in 1765. Her father was a sea captain who died in Honduras when she was an infant. The Rotches two moved to New Bedford, then around 1801 relocated to Hartford, Connecticut, where Thomas became a farmer and wool manufacturer. His sheep were of the Merino breed, which originated in Spain and had exceptionally fine wool. Who first imported Merinos into the United States is debatable. One story says that William Foster of Boston sent three of the animals to Andrew Craigie in Cambridge. When Foster asked him a few years later where the sheep were, Craigie replied that he’d eaten them. He had no idea about their true value.

E.I du Pont, a French immigrant, was responsible for expanding their population in the United States. He arrived in America in 1800 and there established a gunpowder making factory. The next year he headed back to France to procure needed equipment and skilled workers. He was asked to take four Merinos with him on the ship back to America, one of which he would keep for himself. Only one, a ram named Don Pedro, survived the voyage. Du Pont immediately put him to work impregnating as many ewes as he could manage, which he did for at least ten years.

E.I du Pont, a French immigrant, was responsible for expanding their population in the United States. He arrived in America in 1800 and there established a gunpowder making factory. The next year he headed back to France to procure needed equipment and skilled workers. He was asked to take four Merinos with him on the ship back to America, one of which he would keep for himself. Only one, a ram named Don Pedro, survived the voyage. Du Pont immediately put him to work impregnating as many ewes as he could manage, which he did for at least ten years.

Upstairs Hall

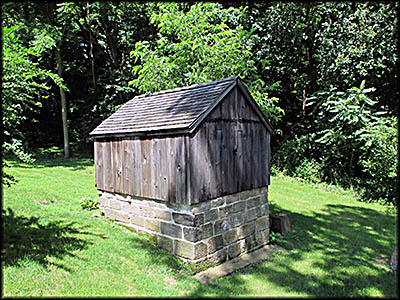

Out Building

Merinos were introduced into Muskingum County in 1807. Until near the end of the nineteenth century most Ohio sheep farmers, especially those in the northeast part of the state, preferred this breed. Spurred by a demand in wool during the Civil War and a lack of Southern cotton, Ohio became a major wool producer. Between 1868 and 1940 it had the highest density of sheep per square mile in the nation.

Spring Hill House was more than just the place where the Rotches made their living. It was also a stop along the Underground Railroad, about which more is covered in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio in the chapter about Stark County. Ohio was a hotbed of Underground Railroad activity and its members were quite diverse. William M. Mitchell was a former slave from North Carolina who later became an Underground Railroad conductor. He lived in Ohio near the Ohio-Kentucky border.

One night a young black man knocked on his door. Though no words verifying this were uttered, Mitchell immediately knew the man was an escaped slave and needed help, so he let him in. Before he could move the fugitive elsewhere, slave-catchers surrounded Mitchell’s house, which stood alone and from which he couldn’t possibly move the escapee without being seen. Terror struck Mitchell. Caught with this man in his house, he would be fined $1,000, something he could ill afford because he had a wife and children to take care of. The slave-catchers insisted on being let in, but Mitchell refused. This would only delay the inevitable. The hunters would soon return with a warrant. His wife went into action. She dressed the fugitive up as a woman and walked out of the house right past the slave-catchers with her “friend.” A warrant was secured but found no escaped slave.

Spring Hill House was more than just the place where the Rotches made their living. It was also a stop along the Underground Railroad, about which more is covered in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio in the chapter about Stark County. Ohio was a hotbed of Underground Railroad activity and its members were quite diverse. William M. Mitchell was a former slave from North Carolina who later became an Underground Railroad conductor. He lived in Ohio near the Ohio-Kentucky border.

One night a young black man knocked on his door. Though no words verifying this were uttered, Mitchell immediately knew the man was an escaped slave and needed help, so he let him in. Before he could move the fugitive elsewhere, slave-catchers surrounded Mitchell’s house, which stood alone and from which he couldn’t possibly move the escapee without being seen. Terror struck Mitchell. Caught with this man in his house, he would be fined $1,000, something he could ill afford because he had a wife and children to take care of. The slave-catchers insisted on being let in, but Mitchell refused. This would only delay the inevitable. The hunters would soon return with a warrant. His wife went into action. She dressed the fugitive up as a woman and walked out of the house right past the slave-catchers with her “friend.” A warrant was secured but found no escaped slave.

Slave-catchers such as these plagued Ohio. One was Bill Shea. In 1841 he was sent to retrieve Clara and George, a brother and sister who had escaped from their Kentucky master, Major Curtis, when he unexpectedly sold Clara to a man who said she would fetch him $3,000 in New Orleans. Unwilling to be separated, the pair fled first southeast, then northeast into the mountains. Some four weeks later they crossed over the into Ohio via Parkersburg, Virginia (now West Virginia). By this point the Underground Railroad was conducting them north.

Shea was persistent and refused to give up his quarry. He sent spies at all the lake ports stretching from Cleveland to Buffalo, New York. Major Curtis settled himself in Cleveland while Shea continued his vigilant search along the most likely routes. Clara and George had in the meantime made their way to Oberlin. When Shea lost the trail, he returned to Cleveland to consult with Curtis. They decided to take a steamer to Sandusky and from there a stage to Cincinnati.

The steamboat they chose was commanded by Captain T.J. Titus. Just after departing, Shea and Curtis learned the boat would go directly to Detroit before making its way back to Sandusky. As the steamer made her way there, Shea saw two people dressed as sailors and, upon closer inspection, realized they were the two he sought! Curtis took them to Captain Titus fully expecting him to release them into his custody. Curtis asked Titus asked how long these two been in his employ. And did he know one was a girl? Titus denied all knowledge of them. Curtis offered him $100 if he would let Curtis and Shea board another boat in the Detroit River. The captain agreed but refused to take any money.

Titus had no love for slavery, a view he had come by when his previous vessel, the Erie, caught fire near Silver Creek, New York, on August 9, 1841. During the conflagration his black steward rose to the occasion and saved the life of his captain. On the pretext of needing wood for the boiler, Titus diverted his boat to Malden, Canada. A furious Curtis offered Titus $1,000 not to dock. He also pointed out that Titus had promised to let him off on another boat on the Detroit River. Titus replied that he had, but he’d said nothing about the slaves. When Curtis began spewing abusive language at Titus, he told him to stop else he’d have him arrested. Clara and George gained their freedom. It is said two years later they were running a prosperous business.🕜

Shea was persistent and refused to give up his quarry. He sent spies at all the lake ports stretching from Cleveland to Buffalo, New York. Major Curtis settled himself in Cleveland while Shea continued his vigilant search along the most likely routes. Clara and George had in the meantime made their way to Oberlin. When Shea lost the trail, he returned to Cleveland to consult with Curtis. They decided to take a steamer to Sandusky and from there a stage to Cincinnati.

The steamboat they chose was commanded by Captain T.J. Titus. Just after departing, Shea and Curtis learned the boat would go directly to Detroit before making its way back to Sandusky. As the steamer made her way there, Shea saw two people dressed as sailors and, upon closer inspection, realized they were the two he sought! Curtis took them to Captain Titus fully expecting him to release them into his custody. Curtis asked Titus asked how long these two been in his employ. And did he know one was a girl? Titus denied all knowledge of them. Curtis offered him $100 if he would let Curtis and Shea board another boat in the Detroit River. The captain agreed but refused to take any money.

Titus had no love for slavery, a view he had come by when his previous vessel, the Erie, caught fire near Silver Creek, New York, on August 9, 1841. During the conflagration his black steward rose to the occasion and saved the life of his captain. On the pretext of needing wood for the boiler, Titus diverted his boat to Malden, Canada. A furious Curtis offered Titus $1,000 not to dock. He also pointed out that Titus had promised to let him off on another boat on the Detroit River. Titus replied that he had, but he’d said nothing about the slaves. When Curtis began spewing abusive language at Titus, he told him to stop else he’d have him arrested. Clara and George gained their freedom. It is said two years later they were running a prosperous business.🕜

Door Stops