Spirit of ’76 Museum

Spirit of ’76 Museum

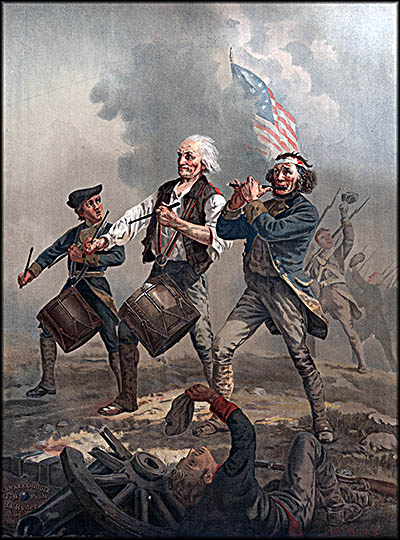

Spirit of ’76 by Archibald Willard

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Drum used as a model for the Spirit of ’76 painting.

During his childhood years, he showed a clear love and talent for art and left it in all sorts of unexpected places. Family lore says he drew an unflattering portrait of his father inside the family outhouse for which the budding artist received a sound thrashing. The entire Willard family moved to Wellington in 1855 when Archibald’s father was made the minster for the Disciples of Christ Church. Here Willard grew to his impressive height of six foot three inches and, along with his brother Charles, joined the Wellington Cornet Band. Willard was apprenticed to E.S. Tripp, a wagonmaker, wheelwright, and decorative artist who had a shop in Wellington.

Upon the outbreak of the Civil War, Willard enlisted in the Eighty-sixth Ohio Voluntary Infantry as a color sergeant, the person who carries the battle flag and one of the most dangerous occupations on the battlefield. His unit saw action in Tennessee and Kentucky. When time allowed, he drew pictures of life in the army, even selling a few to his fellow soldiers. Mustered out in February 1864, he returned to Wellington to marry his childhood sweetheart, Nellie S. Challacombe, then reenlisted a year later, this time as a private in the One hundred seventy-seventh Ohio Volunteers with whom he saw action in Nashville.

Upon the outbreak of the Civil War, Willard enlisted in the Eighty-sixth Ohio Voluntary Infantry as a color sergeant, the person who carries the battle flag and one of the most dangerous occupations on the battlefield. His unit saw action in Tennessee and Kentucky. When time allowed, he drew pictures of life in the army, even selling a few to his fellow soldiers. Mustered out in February 1864, he returned to Wellington to marry his childhood sweetheart, Nellie S. Challacombe, then reenlisted a year later, this time as a private in the One hundred seventy-seventh Ohio Volunteers with whom he saw action in Nashville.

The Spirit of ’76 Museum takes it name from the painting The Spirit of ’76, a work by one of Wellington’s most famous residents, Archibald McNeal Willard. Willard was not a native of Wellington nor was his painting originally named The Spirit of ’76. He was born on August 22, 1836, in Bedford, Ohio, on August 22, 1883, and the title he bestowed upon his most famous work was originally Yankee Doodle. One of seven children, he was the son of the preacher Reverend Samuel Willard. Living with the family was his grandfather, a Revolutionary War veteran who had served with Vermont’s Green Mountain Boys. It was the stories he told about his experiences that shaped Archibald’s vision for The Spirit of ’76.

Never wounded, the war nearly killed him all the same. Dysentery, that terrible and often bloody evacuation of the bowels, might have ended his life had not his good friend from Wellington, Harry Bennett, nursed him back to health. Few realize that diseases like this one killed two-thirds of all the soldiers listed as dead during the Civil War, a much grimmer success rate than bullets, bayonets and artillery. With the way communicable diseases were spread still not understood, armies considered this a part of war and counted those who died of them as causalities.

After the war Willard decided to paint a large panorama filled with scenes of that conflict measuring six feet high by twelve long that could be rolled up for transport from one exhibition place to another. Accompanied by a lecture, it failed to make money. No one wanted to be reminded of the recent war in which so many were lost. So he stored it in a barn and went back to work at Tripp’s shop alongside several of his brothers.

While Willard was capable of realistic art—some of it good and some not—he had a special talent for caricatures with whimsical topics. It was just such a painting that gave him the breakthrough he needed to become a professional artist. Titled Pluck, it showed two frightened children (his) in a wagon being pulled at breakneck speed by the family dog. Willard sent it off to Cleveland to be framed. While there James F. Ryder, a photographer and art dealer, saw it.

After the war Willard decided to paint a large panorama filled with scenes of that conflict measuring six feet high by twelve long that could be rolled up for transport from one exhibition place to another. Accompanied by a lecture, it failed to make money. No one wanted to be reminded of the recent war in which so many were lost. So he stored it in a barn and went back to work at Tripp’s shop alongside several of his brothers.

While Willard was capable of realistic art—some of it good and some not—he had a special talent for caricatures with whimsical topics. It was just such a painting that gave him the breakthrough he needed to become a professional artist. Titled Pluck, it showed two frightened children (his) in a wagon being pulled at breakneck speed by the family dog. Willard sent it off to Cleveland to be framed. While there James F. Ryder, a photographer and art dealer, saw it.

Impressed, he personally delivered the framed Pluck so he could ask Willard to paint a sequel showing viewers how the race ended. Willard obliged with Pluck No. 2 in which the wagon hit a log and threw the children out. Ryder copyrighted both paintings, then had them made into chromolithographs to be sold to the general public with the proceeds being split between the partners fifty-fifty. At the time it was thought humorous art wouldn’t sell, but the gamble paid off. The initial run of 2,000 prints ran out and in the end 10,000 were sold.

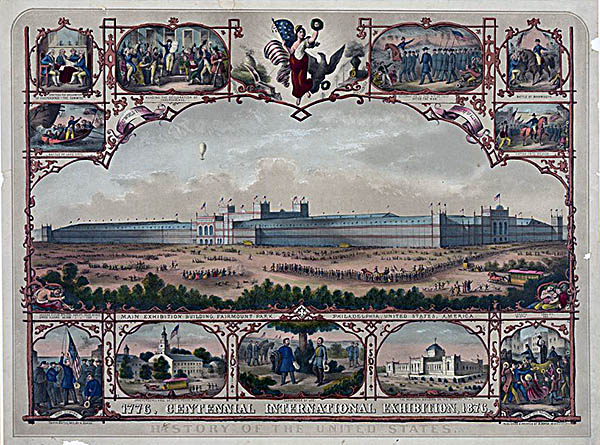

In 1873 Willard began painting in the studio of Willis Adams near Cleveland Public Square. Here he developed his crayon sketch The Fourth of July Musicians into the painting Yankee Doodle, a name suggested by Ryder, who also thought it would be a good idea for Willard to display his new work at the upcoming the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia. This was an international trade fair held to celebrate the platinum jubilee for the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Taking ten years of planning and $11 million to put together, it covered over 450 acres and stood upon Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park. Officially opened by President Ulysses S. Grant on May 10, 1876, the exhibition had 30,000 exhibitors and attracted over 10 million people.

In 1873 Willard began painting in the studio of Willis Adams near Cleveland Public Square. Here he developed his crayon sketch The Fourth of July Musicians into the painting Yankee Doodle, a name suggested by Ryder, who also thought it would be a good idea for Willard to display his new work at the upcoming the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia. This was an international trade fair held to celebrate the platinum jubilee for the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Taking ten years of planning and $11 million to put together, it covered over 450 acres and stood upon Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park. Officially opened by President Ulysses S. Grant on May 10, 1876, the exhibition had 30,000 exhibitors and attracted over 10 million people.

Yankee Doodle showed two men and boy marching on a battlefield, each playing an instrument. The figures were life size upon a canvas ten feet height and eight feet wide. The model for the boy was Henry K. Devereux, a reluctant subject who would rather have played than stand still in front of Willard. The fifer was Hugh Mosher, Willard’s friend and a comrade during the Civil War who had been seriously wounded playing that instrument for the Forty-third Infantry Regiment. The old drummer was none other than Willard’s father.

Art critics had little good to say about it. Those running the Centennial’s art exhibit put into a room of its own to keep it out of the main gallery. No matter. Visitors loved it. Even President Grant took time out to admire it. After the fair ended, Devereux’s father, General John H Devereux, president of the Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati & Indianapolis Railroad, bought the painting.

Willard moved his family to Cleveland. In addition to selling chromographs of The Spirit of ‘76, he painted multiple copies without bothering to leave records as to which one was the first, though most art historians consider the one hanging in the Selectmen's Room at Abbot Hall in Marblehead, Massachusetts, the original. One of his copies hung at the Spirt of ’76 Museum when I visited, but it was only on loan. Most visitors have to be satisfied viewing a printed reproduction. The drum Willard used as the model for this painting is here on permanent display.

Art critics had little good to say about it. Those running the Centennial’s art exhibit put into a room of its own to keep it out of the main gallery. No matter. Visitors loved it. Even President Grant took time out to admire it. After the fair ended, Devereux’s father, General John H Devereux, president of the Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati & Indianapolis Railroad, bought the painting.

Willard moved his family to Cleveland. In addition to selling chromographs of The Spirit of ‘76, he painted multiple copies without bothering to leave records as to which one was the first, though most art historians consider the one hanging in the Selectmen's Room at Abbot Hall in Marblehead, Massachusetts, the original. One of his copies hung at the Spirt of ’76 Museum when I visited, but it was only on loan. Most visitors have to be satisfied viewing a printed reproduction. The drum Willard used as the model for this painting is here on permanent display.

1876 Centennial Exhibit: "History of the United States"

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Inside the Spirit of ’76 Museum

Victorian Bedroom

Inside the Spirit of ’76 Museum

The museum possesses quite a few original Willard paintings, some of which are in dire need of restoration. All are displayed on the first floor along with a scattering of other objects. The upper floors are packed with artifacts from Wellington with items stuffed in every nook and cranny, some of it of questionable value. It is doubtful, for example, that anyone is remotely interested in seeing the Wellington Water Treatment Plant’s very first Omega Dry Chemical Feeder water purifier. And surely there is a more appropriate place to display collection of items from the Congo brought back home from missionary Ruth Hege than among an exhibit of items from Wellington’s fire department. On the same floor is another exhibit containing an extensive array of military uniforms and other war memorabilia donated by locals who served in the U.S. armed forces, such as Lyle K. Morgan, who died in World War I on October 26, 1918.

The mural in an alley that separates the Spirit of ’76 Museum's building from the one next to it celebrates Wellington's history as the one-time largest cheese making center in the United States.

GRANDSON: What’d we do with Grandma’s collection of creepy clown dolls?

GRANDDAUGHTER: Hmm. Shame to throw them away. She spent her whole life collecting them.

GRANDSON: Hang on. Google says there’s the Klown Doll Museum in Plainview, Nebraska. We’ll give it to them!

GRANDDAUGHTER: Nah, too much trouble. Too far away. I know. We’ll give it to the Historical Society. They’ll take anything!

GRANDDAUGHTER: Hmm. Shame to throw them away. She spent her whole life collecting them.

GRANDSON: Hang on. Google says there’s the Klown Doll Museum in Plainview, Nebraska. We’ll give it to them!

GRANDDAUGHTER: Nah, too much trouble. Too far away. I know. We’ll give it to the Historical Society. They’ll take anything!

I’m not trying to pick on this museum in particular but rather using it as an example of an mistake that many small (and even large) museums make, which is they put every object donated on display whether it is worthy of being seen or not. Several museum curators told me they accept all donations but don’t put it all on display for lack of room. The Smithsonian, for example, shows less than two percent of what it owns to the public. Local historical societies can become a dumping ground for items or collections that someone thinks is valuable but has no desire to keep. Possibly a conversation like this precedes a donation:

Probably the most famous politician from the Wellington area is Myron T. Herrick. Born in near Huntington on October 9, 1854, he was the son of farmers who became a lawyer, businessman, real estate speculator, and banker. Belonging to the Republican Party in an era when it had a progressive wing, his political career began when he was elected to Cleveland’s city council in 1885 and culminated with his election as Ohio’s governor in 1902. In 1903 while still governor-elect of Ohio, he endowed Wellington’s Herrick Memorial Library with $20,000. Later he gave it another $70,000. In 1912, President Howard Taft appointed him the ambassador to France. When Woodrow Wilson replaced Taft, he asked Herrick to stay at his post until December 1914.

In August 1914 World War I broke with France becoming a prime battleground. Herrick rose to the occasion, helping stranded Americans get out of Europe. When the Germans appeared close to reaching Paris, the French government and many diplomats decamped for fear the Germans were going to take the city. Herrick remained. He took over the duties of many of many embassies, including those of Japan, Turkey and Serbia. He also helped civilian German and Austro-Hungarian subjects get home. He founded the American Relief Clearing House to care for orphans, the disabled, and widows. For his herculean efforts, the French awarded him the Grand Cross of the Order of the Legion of Honor.

The museum’s home, Wellington, was once one of the largest cheese storage and transportation hubs in the United States, but that is something covered fully in the chapter about Lorain County in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio.🕜

In August 1914 World War I broke with France becoming a prime battleground. Herrick rose to the occasion, helping stranded Americans get out of Europe. When the Germans appeared close to reaching Paris, the French government and many diplomats decamped for fear the Germans were going to take the city. Herrick remained. He took over the duties of many of many embassies, including those of Japan, Turkey and Serbia. He also helped civilian German and Austro-Hungarian subjects get home. He founded the American Relief Clearing House to care for orphans, the disabled, and widows. For his herculean efforts, the French awarded him the Grand Cross of the Order of the Legion of Honor.

The museum’s home, Wellington, was once one of the largest cheese storage and transportation hubs in the United States, but that is something covered fully in the chapter about Lorain County in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio.🕜

It is unlikely anyone visiting a local history museum is going to be interested in seeing the Wellington's very first Omega water purifier, but just in case, here it is in all its glory.

Myron T. Herrick

Library of Congress

Library of Congress