Shaker Historical Museum

Shaker Historical Museum

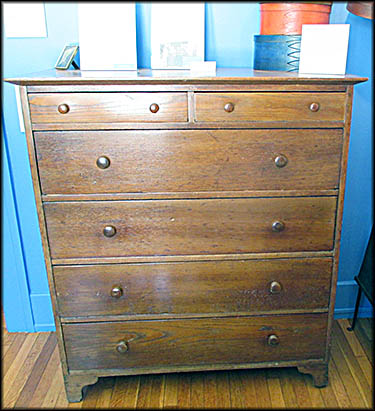

Shaker-made Furniture

A combination of homemade meatballs, a laundry basket, and a cat led me down that road that took me to the Shaker Historical Museum. The meatballs in question are large: I eat one per serving of spaghetti and make a dozen at a time, then freeze the rest in containers. If I seal a container and throw it into the freezer immediately, the meatballs freeze so tightly together it’s hard if not impossible to separate them. I solved this problem by allowing them to cool to room temperature first.

In the days before I had a cat, letting them cool wasn’t a problem. But my furry friend is a mistress of problem solving when it comes to getting at food she wants. When she first arrived in my home I protected the cooling meatballs with an upside-down laundry basket on top of which was a heavy book. Undaunted, kitty simply reached through the basket’s holes. So I bought a new laundry basket with holes too small for her to get her paws through. Alas, there are those pesky hand holds, and it was through one of these plus quite a bit of pushing that gave her the access needed to extend a claw into the meatballs and pull out tiny pieces. Finally I put the laundry basket on a table against a wall so she couldn’t scoot it. A crashing sound alerted me to something amiss and I caught her just about to eat a meatball that had fallen to the floor.

At this point I admitted defeat and thought what I really needed was a pie safe. For those of you unfamiliar with this, it is a sort of cupboard into which people in Nineteenth Century America locked away food to keep animals out. My quest for instructions on making one soon led me to the Shakers, who to this day are famous for their furniture. This in turn peaked my interest in the Shakers themselves. As it happens, there is a museum dedicated to their in Shaker Heights, Cleveland. This being about an hour and fifteen minutes from my house, I decided to visit one cold Sunday.

In the days before I had a cat, letting them cool wasn’t a problem. But my furry friend is a mistress of problem solving when it comes to getting at food she wants. When she first arrived in my home I protected the cooling meatballs with an upside-down laundry basket on top of which was a heavy book. Undaunted, kitty simply reached through the basket’s holes. So I bought a new laundry basket with holes too small for her to get her paws through. Alas, there are those pesky hand holds, and it was through one of these plus quite a bit of pushing that gave her the access needed to extend a claw into the meatballs and pull out tiny pieces. Finally I put the laundry basket on a table against a wall so she couldn’t scoot it. A crashing sound alerted me to something amiss and I caught her just about to eat a meatball that had fallen to the floor.

At this point I admitted defeat and thought what I really needed was a pie safe. For those of you unfamiliar with this, it is a sort of cupboard into which people in Nineteenth Century America locked away food to keep animals out. My quest for instructions on making one soon led me to the Shakers, who to this day are famous for their furniture. This in turn peaked my interest in the Shakers themselves. As it happens, there is a museum dedicated to their in Shaker Heights, Cleveland. This being about an hour and fifteen minutes from my house, I decided to visit one cold Sunday.

The only thing I knew about the Shakers was something I recalled reading long ago, probably in a history textbook: because they were celibate, they ran orphanages to produce their next generation. When the U.S. the government shut them down, the Shaker religion died out since celibates can’t produce children. When I mentioned this to one of the museum’s employees, she explained that this bit of lore was not true. Naturally I had to investigate this further. I’ll get to that later.

The city of Shaker Heights began as the North Union Shaker Colony, which was founded by Ralph Russell. He first visited the area in 1811 when it was owned by Connecticut and known as the Western Reserve. The next year he bought some land and built a cabin in what is now Warrensville Heights, just in time for a war between the United States and Great Britain to break out. So far as I can tell, the museum makes no mention of whether or not this conflict affected Russell and his family. The death of Russell’s father in 1821 caused him much person pain, and he sought comfort among the Union Valley Shakers residing in Lebanon, Ohio. After spending months with them, he returned home and began, according to one the museum’s information signs, “converting his relatives and neighbors” to the religion. He established the North Union Shaker Colony on farmland owned by his family.

The Shakers are an offshoot of the Quakers and originate in England. They were sometimes called “Shaking Quakers” because of their enthusiastic dancing, online examples of which are few and not especially useful. In America they incorporated as the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearance. Though a convert rather than a founder, the most important person in this religion’s history was Ann Lee, an illiterate woman born in 1736 in Manchester, England. After bearing and losing four children, she came to the belief she had been punished by God for the sin of sexual relations and began arguing for celibacy, which was adopted by most Shakers. She believed herself to be the female version of Jesus Christ and argued for the total equality of men and women. She moved to America with her husband and seven others in 1774 to establish a community there. Though not especially successful at first, their effort ultimately bloomed and spread.

The city of Shaker Heights began as the North Union Shaker Colony, which was founded by Ralph Russell. He first visited the area in 1811 when it was owned by Connecticut and known as the Western Reserve. The next year he bought some land and built a cabin in what is now Warrensville Heights, just in time for a war between the United States and Great Britain to break out. So far as I can tell, the museum makes no mention of whether or not this conflict affected Russell and his family. The death of Russell’s father in 1821 caused him much person pain, and he sought comfort among the Union Valley Shakers residing in Lebanon, Ohio. After spending months with them, he returned home and began, according to one the museum’s information signs, “converting his relatives and neighbors” to the religion. He established the North Union Shaker Colony on farmland owned by his family.

The Shakers are an offshoot of the Quakers and originate in England. They were sometimes called “Shaking Quakers” because of their enthusiastic dancing, online examples of which are few and not especially useful. In America they incorporated as the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearance. Though a convert rather than a founder, the most important person in this religion’s history was Ann Lee, an illiterate woman born in 1736 in Manchester, England. After bearing and losing four children, she came to the belief she had been punished by God for the sin of sexual relations and began arguing for celibacy, which was adopted by most Shakers. She believed herself to be the female version of Jesus Christ and argued for the total equality of men and women. She moved to America with her husband and seven others in 1774 to establish a community there. Though not especially successful at first, their effort ultimately bloomed and spread.

After Ann’s death at the age of forty-eight, those who followed codified Shaker theology and practices. Shakers, always pacifists, lived in communal homes in which men and women were segregated to ensure no funny business happened between them. Individuals owned nothing; all belonged to the “family.” While the Shakers were not the first or only religion to practice communalism, they are certainly one of the longer lasting ones. Shakers were humanitarians. They believed in charity for the less fortunate without expecting anything in return, which explains why they took in so many orphans, whom they fed and gave an education. So far as I could find, no Shaker community ran an official orphanage and the U.S. government never intervened with their care of orphans, who were in any case not the crop from which Shakers gained adherents. In the age of pessimism and economic turmoil between the founding of the United states until about the 1830s, many turned to religion as a means of understanding a world without much opportunity.

The collapse of the Shakers was gradual and caused by a variety of factors. And while celibacy didn’t help matters cause, it wasn’t that import. We know this because other communal groups who did reproduce such as those at Zoar Village still disbanded. The Shaker population suffered one of its biggest blows during the chaos of the Civil War (from which, incidentally, President Lincoln exempted them because of their well-known pacifism). Communities in areas of conflict suffered from theft and destruction of property. It was after the war that the most significant reason for their eventual extinction occured. According to the scholarly article “The Rise and Decline of the Shakers” by C. Allyn Russell from which much of the information in this paragraph is taken, “the Shakers relied for converts upon those who had grown disillusioned with the world.” When the American West opened up after the Civil War, the opportunity for free or cheap land and other untapped resources caused a mass exodus of those raised by the Shakers to the frontier.

The collapse of the Shakers was gradual and caused by a variety of factors. And while celibacy didn’t help matters cause, it wasn’t that import. We know this because other communal groups who did reproduce such as those at Zoar Village still disbanded. The Shaker population suffered one of its biggest blows during the chaos of the Civil War (from which, incidentally, President Lincoln exempted them because of their well-known pacifism). Communities in areas of conflict suffered from theft and destruction of property. It was after the war that the most significant reason for their eventual extinction occured. According to the scholarly article “The Rise and Decline of the Shakers” by C. Allyn Russell from which much of the information in this paragraph is taken, “the Shakers relied for converts upon those who had grown disillusioned with the world.” When the American West opened up after the Civil War, the opportunity for free or cheap land and other untapped resources caused a mass exodus of those raised by the Shakers to the frontier.

The end of the North Union Shaker Colony caused those who remained to head east in 1889 and join up with another community there. When the village of Shaker Heights incorporated in 1911, it had within its bounds a grand total of 200. Much of this abandoned land was purchased by brothers Oris Paxton and Mantis James Van Sweringen, who were neither Shakers nor descended from them. Originally from around Wooster, they had moved to Cleveland with their family about 1890. To develop the village, they needed a streetcar connection into Cleveland. Failing to convince the Cleveland Railway Company to expand to the village, in 1911 the brothers started the Cleveland and Youngstown Railroad Company that would built its own streetcar system. This began buying up land in a ravine known as Kingsbury Run. When a piece of it turned out to be owned by the Nickel Plate Railroad, the brothers bought this in 1916, allowing them to finally complete their rapid line into Cleveland. They also had a real estate business, which appropriated the village’s former Shaker presence in its advertising to attract buyers. Their effort to connect Shaker Heights with Cleveland culminated in the construction of the Terminal Tower, which was completed in 1930 just in time for the brothers to lose their fortune to the Great Depression.

The Shaker Historical Museum is housed in what was originally the family home of Louis and Blanche Myers, who had it built in 1910. The Shaker Historical Society (SHS) was founded in 1947 and moved into its current location in 1969 when Frank Myers—one of the SHS’s trustees—donated it for that purpose. The fact that the Ohio History Connection, the chronically underfunded official state historical society, is associated with it gave me pause because some of the sites they run are in a sorry state. Here, it turns out, I needn’t have worried. The house looked like it was in excellent shape to my uninformed eye, and its exhibits were expertly presented. And unlike a lot of local historical societies, it displays artifacts and items that are significant and not any old thing that had been donated to it.

The Shaker Historical Museum is housed in what was originally the family home of Louis and Blanche Myers, who had it built in 1910. The Shaker Historical Society (SHS) was founded in 1947 and moved into its current location in 1969 when Frank Myers—one of the SHS’s trustees—donated it for that purpose. The fact that the Ohio History Connection, the chronically underfunded official state historical society, is associated with it gave me pause because some of the sites they run are in a sorry state. Here, it turns out, I needn’t have worried. The house looked like it was in excellent shape to my uninformed eye, and its exhibits were expertly presented. And unlike a lot of local historical societies, it displays artifacts and items that are significant and not any old thing that had been donated to it.

Different rooms cover different topics. One is about the North Union Shakers. Another looks into the history of Shaker Heights in general and the two brothers who made into a prosperous city, the Van Sweringens, in particular. Still another room contains the limited time “Shaker Eats!” exhibit, which examines food, restaurants and grocery stores throughout Shaker Heights’ history. Going up the stairs you see some contemporary art along the wall with more on the floor above, which, so far as I’m concerned, isn’t especially good or interesting. Two of the upstairs rooms are about Shaker life.

For those who know nothing about Shaker history or the history of Shaker Heights, a visit to this little gem of a museum is well worth it. Although I’ve been in some of the world’s best museums, I’ve always been amazed and impressed with what much smaller ones known mainly on a local level can do. While a visit will probably only last one to two hours, you will leave with more knowledge in your head than you know what to do with.🕜

For those who know nothing about Shaker history or the history of Shaker Heights, a visit to this little gem of a museum is well worth it. Although I’ve been in some of the world’s best museums, I’ve always been amazed and impressed with what much smaller ones known mainly on a local level can do. While a visit will probably only last one to two hours, you will leave with more knowledge in your head than you know what to do with.🕜