Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library and Museums

Rutherford B. Hayes Museum Entrance

Rutherford B. Hayes House

This carriage, purchased by Rutherford B. Hayes, was made by the company that eventually turned into Rolls Royce.

If there is one thing Ohio has a surplus of, it’s presidents. It has produced eight chief executives: William Henry Harrison, Ulysses S. Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, Benjamin Harrison, William McKinley, William H. Taft, and Warren G. Harding. William Henry Harrison is a bit iffy because he was born in Virginia but lived in Ohio when he became president, and had also served the state as a congressman and senator. Of those eight, the most well known is by far Ulysses S. Grant, and the least Benjamin Harrison, who was William Henry’s grandson. Interestingly, half of them died in office. Pneumonia took William Henry Harrison, bullets killed Garfield and McKinley, and either heart failure or a stroke got Harding.

History has not treated Rutherford B. Hayes kindly. Most school textbooks remember for losing the election of 1876 to Samuel J. Tilden but ultimately wrested it away from him in the House of Representatives in exchange for ending Reconstruction. He served just one term which, according to the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library and Museums, was quite the success. He ended the corruption that had plagued the Grant Administration, and under his watch the economy fully recovered from the Panic of 1873 (an economic depression of epic proportions only outdone by the Great Depression).

Like any person, Hayes was not perfect and the museum did a good job of showing that. One information sign said as a lawyer he “developed a reputation as a dogged defender of the indigent and the insane.” In 1852 he successfully convinced an appeals court that Nancy Farrar, who had poisoned her family with arsenic, should not have been sentenced to death but rather to a lifetime in an asylum (though considering the state of those in the nineteenth century, it wasn’t much better than the alternative). He also vehemently opposed the death penalty, a rarity in that era.

Beyond the fact the history has damned him for ending Reconstruction with the result of nearly a century of Jim Crow, his Indian policies also did not work out so well. He decided the reservation system was a bad idea and needed to go. In this he was probably right considering how miserable those places were, but his solution, made in coordination with Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz, was worse. It was decided Native Americans needed to be fully integrated into American society just like immigrants had, and to that end Hayes allowed Captain Richard H. Pratt to found the notorious Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, which served as the template for attempted cultural genocide: students were punished if they spoke their own language and the curriculum was designed to eviscerate their heritage.

Lucy Hayes’ Wedding Dress

For the first eleven years of my life, Hayes Presidential Library and Museums was known as the Hayes Memorial, which is still what I and most of my family still call it because we only lived about twenty-five minutes away and old habits die hard. The schools in my hometown of Bellevue often sent its elementary students there on fieldtrips, but for some reason my class never went. During my undergraduate days I used its library, and while working for my masters degree in library science a few years ago, I got a behind the scenes tour. It has a pretty spectacular collection and wonderful staff.

During that visit I was given two passes for the museum, which I visited the next year. In May of this year the museum reopened after a complete remodeling. The house, which I had never visited, had undergone a makeover a few years earlier that restored it to what it looked like around 1880. Having always planned to return to see the latter, I figured that while I was at it, I would see the museum as well since it had changed.

During that visit I was given two passes for the museum, which I visited the next year. In May of this year the museum reopened after a complete remodeling. The house, which I had never visited, had undergone a makeover a few years earlier that restored it to what it looked like around 1880. Having always planned to return to see the latter, I figured that while I was at it, I would see the museum as well since it had changed.

My traveling companions and I went through the house first. For this you get a guided tour and are not allowed to take photos (though I snapped one before I knew that, and out of respect for the staff, I will keep it to my private collection). House tours are always iffy things. Some are dry as dust. If you ever find yourself on one where the guide only talks about the architecture or the silverware, run while you can. We lucked out. Our guide was extremely knowledgeable and gave us a very informative and interesting tour, which took a bit over an hour but seemed like it was just fifteen minutes. We even got to ride in the elevator. The one thing I wish we could have done was gone to the third floor and attic above that, but those were closed off. Historic homes with more than two floors almost always have the uppermost ones closed—it must be a museum thing.

I am a connoisseur of museums, and I’ve been to some of the world’s best and worst. I implore the Hayes Presidential Library and Museums to get its money back from whomever did its museum’s remodeling because, while it has its merits, it is overall pretty awful. To begin with, someone thought to include historical scenes and places using cheesy manikins and poorly painted backgrounds. I have written this before and I can’t stress it enough: if you are a museum curator overseeing the creation of displays of this type, unless you have the equivalent of Leonardo da Vinci making them, don’t use them. They look awful.

I am a connoisseur of museums, and I’ve been to some of the world’s best and worst. I implore the Hayes Presidential Library and Museums to get its money back from whomever did its museum’s remodeling because, while it has its merits, it is overall pretty awful. To begin with, someone thought to include historical scenes and places using cheesy manikins and poorly painted backgrounds. I have written this before and I can’t stress it enough: if you are a museum curator overseeing the creation of displays of this type, unless you have the equivalent of Leonardo da Vinci making them, don’t use them. They look awful.

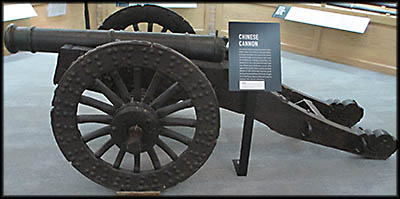

President Hayes’ second son, Webb, became a professional soldier in the U.S. army, serving in all sorts of wars, including the Filipino Insurrection, Boxer Rebellion, and World War I. Colonel Webb brought a lot of stuff home from the various theaters of war in which he served, and these have are on display in the museum. There is a whole room dedicated to weapons of war he collected, including a Chinese cannon. While the room in which you find this display is well done and interesting, it really doesn’t belong in a museum about a president dead before most of these wars occurred. Colonel Webb was also a notorious looter. The museum makes no mention of this, but the two prominent items from China on display, the aforementioned cannon and a Chinese Imperial uniform, were stolen from the Forbidden City during the Boxer Rebellion.

An entire area of the museum’s basement floor is dedicated to the history of the museum itself, and unless you are the Smithsonian or something like it with a storied past, no one cares save for those who work there. Worse, someone decided that if the museum had an item in storage, it needed to be displayed. There is, for example, a pair of spark plugs from a Sandusky-based speedboat manufacturer once owned by one of Hayes’ sons. No one wanted or needed to see that, but it wasn’t the most ridiculous item: that goes to the first IBM computer ever used by the museum! If you want to show that off, send it to the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California.🕜

An entire area of the museum’s basement floor is dedicated to the history of the museum itself, and unless you are the Smithsonian or something like it with a storied past, no one cares save for those who work there. Worse, someone decided that if the museum had an item in storage, it needed to be displayed. There is, for example, a pair of spark plugs from a Sandusky-based speedboat manufacturer once owned by one of Hayes’ sons. No one wanted or needed to see that, but it wasn’t the most ridiculous item: that goes to the first IBM computer ever used by the museum! If you want to show that off, send it to the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California.🕜

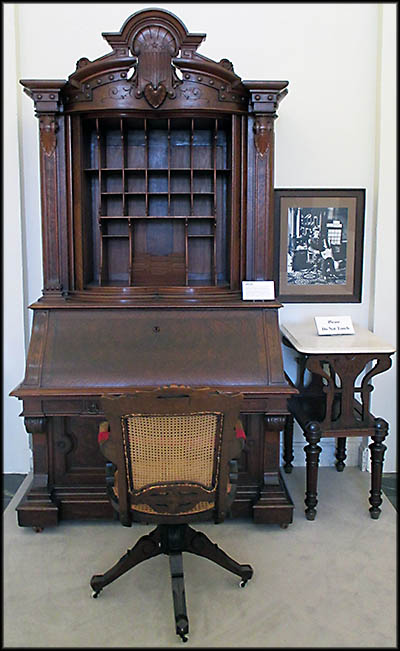

President Ulysses S. Grant’s White House Desk

This Chinese Imperial Uniform was “acquired” (as its information sign says) from China. In other words, it was looted.

This Chinese cannon was looted from the Forbidden City in Peking (Beijing).

These spark plugs are on display in a museum dedicated to a president who served from 1877-1881. Really?

Museum curators take note: if your “scene” looks like the above, get rid of it. It will make your museum look far better.