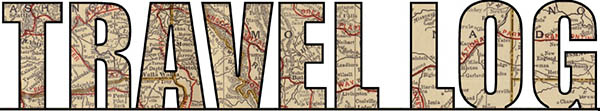

Museum of the American Revolution

Entrance

This low relief sculptured version of Emanuel Leutze's painting Washington Crossing the Delaware in on the museum's exterior.

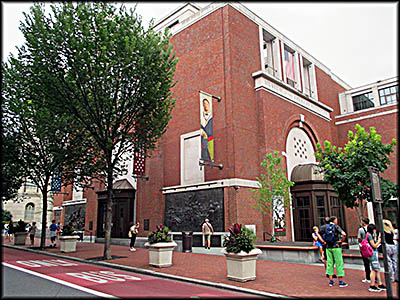

Paul Revere's engraving of the Boston Massacre was a masterclass in propaganda. It ignores that the colonists were harassing the British soldiers and throwing things at them.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

This is one of several interactive touchscreens you can use for a more in depth look at different aspects of the American Revolution.

Museums rarely allow visitors to touch authentic historic artifacts, so here's an exception. You can touch this late 18th century gun as much as you'd like.

This brawl between New Englanders and Virginans in Harvard Yard was broken up by George Washington.

Inside the Museum

Bronze relief of the signing of the Declaration of Independence based on the one found in the Rotunda at the U.S. Capitol.

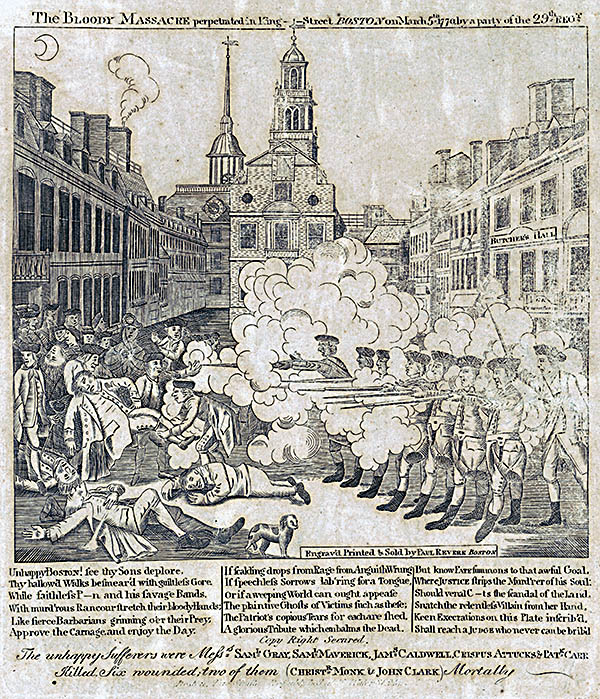

Upon the conclusion of the French and Indian War, the British Parliament passed a tax on cider and peery. It didn't go down well with the British people, as shown on this teapot.

Mary Perth rejoiced when Lord Dunmore, Virginia's last royal governor, offered freedom to slaves who joined his army. Mary immediately ran away and joined up. Later she and other former slaves founded a colony in Africa and celebrated Dunmore's proclamation as the "Day of Jubilee."

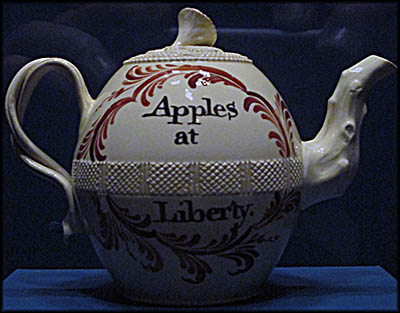

Quakers Benjamin and Mary Humprheys freed their slave, Quansheba, in May 1776. She stayed with the family and worked at their tavern. One of her duties was to clean up, and to do she threw trash into the privy. That's where this teapot came from.

Many Native Americans got caught up in the American Revolution. Some joined with the Americans, some with the British, and others remained neutral.

At the end of the French and Indian War American colonists were enthusiastic supporters of the British Empire. Many owned patriotic items such as this plate, which shows Admiral Edward Vernon's seizure of the Spanish colonial port of Porto Bella. George Washington's Mount Vernon is named in the admiral's honor.

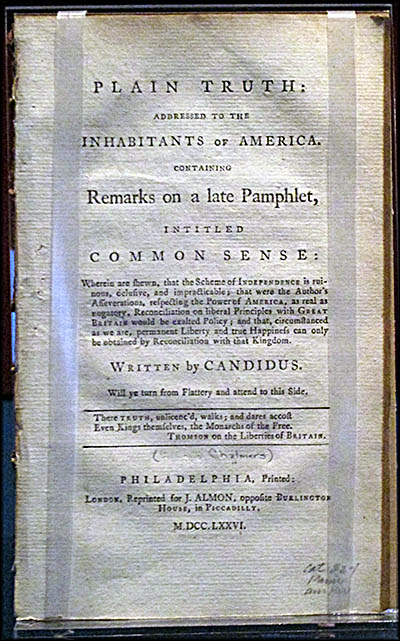

To fortify the Patriot's resolved, Thomas Paine anonymously published Common Sense in January 1776.

American loyalist James Chalmers, using the pen name Candidus, wrote Plain Truth as a counterargument to Common Sense.

The teenager Joseph Plumb Martin joined the Patriot army in 1776 and found battle and its aftermath quite a horror.

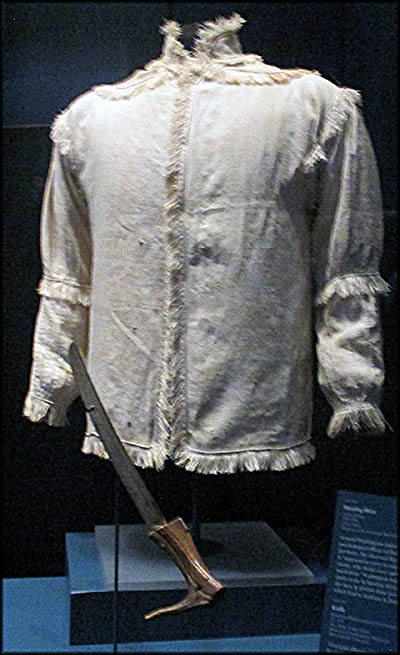

George Washington knew that the hunting shirts worn by his riflemen would sow terror in British soldiers who saw them.

Robert Pleasants gained his freedom by running away and joining the British army as a trumpeter.

Hessian Headgear

Dragoons

Model of the American Privateer Royal Louis

Replica Deck of a Privateer Sloop

Recruited into the British army from his native Ireland, Private William Burke didn't see combat until reaching American shores. In addition to English, he also spoke Irish Gaelic.

After the British captured Philadelphia, they imprisoned some prisoners of war in Independence Hall. Ill-treated, Quaker woman tended to them.

If you know nothing about the War for Independence and you go through the entirety of the Museum of the American Revolution, you may well come out an expert on the topic. If you’re well-versed on the topic, it’s likely you’ll still learn things you didn’t know about. The museum tells the story of the American Revolution from multiple perspectives, the way history needs to be presented.

Plan on taking a couple hours to go through it. This museum is huge. It’s located in the historic district of Philadelphia near Independence Hall, and here I need to give fair warning to curators of other museums: visiting may cause you intense envy. Everything about the museum is top-notch, especially the full-size figures.

You start with the French and Indian War (part of the Seven Years’ War), which was fought between 1754 and 1763 in what is today the United States and Canada. It was during the war that King George III took the throne in 1761. The American colonists celebrated his ascent with parties and fireworks. They saw him as the defender of their liberties. When the British prevailed in the French and Indian War, the colonists felt proud of being part of the worldwide British Empire, which had gained India among other new territories.

Plan on taking a couple hours to go through it. This museum is huge. It’s located in the historic district of Philadelphia near Independence Hall, and here I need to give fair warning to curators of other museums: visiting may cause you intense envy. Everything about the museum is top-notch, especially the full-size figures.

You start with the French and Indian War (part of the Seven Years’ War), which was fought between 1754 and 1763 in what is today the United States and Canada. It was during the war that King George III took the throne in 1761. The American colonists celebrated his ascent with parties and fireworks. They saw him as the defender of their liberties. When the British prevailed in the French and Indian War, the colonists felt proud of being part of the worldwide British Empire, which had gained India among other new territories.

So, what went wrong? Why did the colonists turn on their king and in just thirteen years? The answer is complicated, but one big issue was over money. Wars are expensive, and the British government needed to pay for the one they’d just finished. Taxes were levied in Britain and in the colonies to refill the government’s coffers. In Britain itself, the so-called Cyder Act of 1763 put levies on the transportation and production of cider and peery (a slightly fermented drink made from pears). It mainly affected the poor and proved so unpopular, it was repealed in 1766.

In the colonies, Britain considered itself sovereign over the Native Americans its territory. Many weren’t keen on that. so they decided to push colonists off their land in what became known as Pontiac’s Rebellion. To quell that and keep the peace, Britian sent to the colonies 10,000 regular troops. That, too, cost money. To pay for it and the debt from the French and Indian War, Parliament enacted the Stamp Act in 1765. This required a stamp on all paper items such as newspapers to show that the tax was paid.

The colonists felt that they should impose taxes locally. Out of their protests against the Stamp Act came the slogan, “No taxation without representation!” Parliament repealed the Stamp Act the next year. Other taxes replaced it, and the colonists liked those no better.

In the colonies, Britain considered itself sovereign over the Native Americans its territory. Many weren’t keen on that. so they decided to push colonists off their land in what became known as Pontiac’s Rebellion. To quell that and keep the peace, Britian sent to the colonies 10,000 regular troops. That, too, cost money. To pay for it and the debt from the French and Indian War, Parliament enacted the Stamp Act in 1765. This required a stamp on all paper items such as newspapers to show that the tax was paid.

The colonists felt that they should impose taxes locally. Out of their protests against the Stamp Act came the slogan, “No taxation without representation!” Parliament repealed the Stamp Act the next year. Other taxes replaced it, and the colonists liked those no better.

The slow burn of colonists going from being proud British subjects to wanting independence didn’t happen in a vacuum. Writers, rabblerousers, and creators of propaganda fueled this change. One influencer was Mercy Otis Warren. Born on September 14, 1728, her father served in the Massachusetts legislator, as did her husband, James Warren. Steeped in politics, she wrote poetry, satires and plays skewing the British. She supported boycotts against British goods, something many colonial women did quite effectively. The Daughters of Liberty spearheaded this movement.

Ire against taxes was just one of the issues that upset colonists. They felt their very liberties were under attack, and used the Boston Massacre as evidence. This event occurred on March 5, 1770. That evening, colonists gathered at Boston’s custom house and started harassing the British soldiers guarding it. More troops were inside under the command of Captain Thomas Preston. He ordered them to fix their bayonets and go outside to reinforce the soldiers there.

Colonists starting throwing snowballs, rocks, and other projectiles at the soldiers. When one hit Private Hugh Montgomery, his musket discharged, prompting other soldiers to fire. Five colonists died and another six suffered wounds. A local silversmith, Paul Revere, created a propaganda engraving of the event that showed brutal British soldiers firing on peaceful colonists. Aside from that inaccuracy, he also failed to include an image of Crispus Attucks, the sole African American killed in the confrontation.

Ire against taxes was just one of the issues that upset colonists. They felt their very liberties were under attack, and used the Boston Massacre as evidence. This event occurred on March 5, 1770. That evening, colonists gathered at Boston’s custom house and started harassing the British soldiers guarding it. More troops were inside under the command of Captain Thomas Preston. He ordered them to fix their bayonets and go outside to reinforce the soldiers there.

Colonists starting throwing snowballs, rocks, and other projectiles at the soldiers. When one hit Private Hugh Montgomery, his musket discharged, prompting other soldiers to fire. Five colonists died and another six suffered wounds. A local silversmith, Paul Revere, created a propaganda engraving of the event that showed brutal British soldiers firing on peaceful colonists. Aside from that inaccuracy, he also failed to include an image of Crispus Attucks, the sole African American killed in the confrontation.

Eight soldiers were charged with killing the colonists. At first it seemed no colonial lawyer wanted to defend them. Then John Adams stepped up, doing so to show the British that fair trials could be had in the colonies. Six of the defendants were acquitted, and the other two found guilty of the lesser charge of manslaughter for which their thumbs were branded.

The next event on the road to revolution was the Boston Tea Party. Taxes had nothing to do with this protest. For many years smugglers like Sameul Adams and John Hancock made a fortune selling tea at a cost less than the legal variety. They didn’t take it kindly when the British government reduced the import duties on tea, then gave the East India Company a monopoly on selling it directly in the colonies, cutting out the middlemen. Now their tea cost less than the smuggled variety! To protest, the Sons of Liberty “disguised” as Native Americans boarded a tea ship on December 16, 1773, and dumped the tea overboard into Boston Harbor.

This didn’t go over well in Britain. Parliament passed so-called the Coercive or Intolerable Acts to punish Massachusetts in general and Boston in particular. The Administration of Justice Act gave Massachusetts’s governor the ability to move a trial to another colony or to Britain. The Boston Port Act ordered the blockade of Boston Harbor. The Massachusetts Government Act reduced the power of the locally elected Massachusetts Council and mandated that its members were appointed by the Crown, not elected. The Quartering Act made colonists pay for the quartering of British troops. It didn’t give them the power to forcibly move into people’s houses.

The next event on the road to revolution was the Boston Tea Party. Taxes had nothing to do with this protest. For many years smugglers like Sameul Adams and John Hancock made a fortune selling tea at a cost less than the legal variety. They didn’t take it kindly when the British government reduced the import duties on tea, then gave the East India Company a monopoly on selling it directly in the colonies, cutting out the middlemen. Now their tea cost less than the smuggled variety! To protest, the Sons of Liberty “disguised” as Native Americans boarded a tea ship on December 16, 1773, and dumped the tea overboard into Boston Harbor.

This didn’t go over well in Britain. Parliament passed so-called the Coercive or Intolerable Acts to punish Massachusetts in general and Boston in particular. The Administration of Justice Act gave Massachusetts’s governor the ability to move a trial to another colony or to Britain. The Boston Port Act ordered the blockade of Boston Harbor. The Massachusetts Government Act reduced the power of the locally elected Massachusetts Council and mandated that its members were appointed by the Crown, not elected. The Quartering Act made colonists pay for the quartering of British troops. It didn’t give them the power to forcibly move into people’s houses.

The Intolerable Acts prompted twelve of the thirteen colonies to send delegates to Philadelphia to form the First Continental Congress, which gathered in September 1774. Its purpose was to figure out how to collectively resist British oppression while at the same time working for reconciliation with the king. That didn’t work out.

The Second Continental Congress sent King George the Declaration of Independence, making war unavoidable. The fighting broke out on April 19, 1775. Massachusetts’ royal governor, Thomas Gage, decided he’d head off a possible armed rebellion by sending troops to Concord to seize weapons and powder stored there, and to capture the rebel leaders John Hancock and John Adams.

The Patriots caught wind of the plan. It’s here that Paul Revere made his famous ride to warn others that the British were coming. He only made it as far as Lexington before being captured, but four others also galloped down to roads to spread the word. This prompted the minutemen to turn out, although not all those colonists who’d come to stop the British were minutemen. The rest were militia. The difference: the minutemen were ready to respond to a call immediately, while those in the regular militia might not be able to report to duty right away.

The Second Continental Congress sent King George the Declaration of Independence, making war unavoidable. The fighting broke out on April 19, 1775. Massachusetts’ royal governor, Thomas Gage, decided he’d head off a possible armed rebellion by sending troops to Concord to seize weapons and powder stored there, and to capture the rebel leaders John Hancock and John Adams.

The Patriots caught wind of the plan. It’s here that Paul Revere made his famous ride to warn others that the British were coming. He only made it as far as Lexington before being captured, but four others also galloped down to roads to spread the word. This prompted the minutemen to turn out, although not all those colonists who’d come to stop the British were minutemen. The rest were militia. The difference: the minutemen were ready to respond to a call immediately, while those in the regular militia might not be able to report to duty right away.

6 In Lexington, around seventy to eighty minutemen and militiamen stood in parade formation. Their leader, John Parker, didn’t plan to fight. He wanted to show defiance to the oncoming British soldiers. Against orders, someone fired a shot—no one knows who or which side—and a skirmish broke out. The militia scattered, then reformed and made its way to Concord where a larger battle between the British and Patriots erupted. The British soldiers, tired from a long march and not expecting such resistance, made a fighting retreat back to Boston. The British soldiers failed to apprehend Adams and Hancock.

With colonists fighting a war for their liberty, enslaved Blacks had to decide which side to take. They wanted freedom, and when the last royal governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore (John Murray), offered it to anyone who fought for the Crown, many slaves ran away to join with him. Throughout the war the British offered this deal. One such person who took it up was London Pleasants, a fifteen-year-old Virginian. He ran away and joined a British army under the command of General Bendict Arnold on January 6, 1781.

Some Patriots did free their slaves. Philadelphia Quakers Benjamin and Mary Humphreys, who ran an unlicensed tavern, freed Quansheba Morgan in May 1776 at a Meeting House. After her manumission, she stayed with the family, working in their tavern. In his will, Benjamin stipulated that after his death, Quansheba should be taken care of by his estate for the rest of her life.

With colonists fighting a war for their liberty, enslaved Blacks had to decide which side to take. They wanted freedom, and when the last royal governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore (John Murray), offered it to anyone who fought for the Crown, many slaves ran away to join with him. Throughout the war the British offered this deal. One such person who took it up was London Pleasants, a fifteen-year-old Virginian. He ran away and joined a British army under the command of General Bendict Arnold on January 6, 1781.

Some Patriots did free their slaves. Philadelphia Quakers Benjamin and Mary Humphreys, who ran an unlicensed tavern, freed Quansheba Morgan in May 1776 at a Meeting House. After her manumission, she stayed with the family, working in their tavern. In his will, Benjamin stipulated that after his death, Quansheba should be taken care of by his estate for the rest of her life.

7 Britian had the world’s best army and despite their initial success, minutemen and militia weren’t going to last long against this force. Realizing this, the Continental Congress established a regular army over which they gave Geroge Washington command. To say that the fighting force that Washington had when the war started was an army is being generous.

A lack of discipline was one of its biggest problems, an issue exasperated by regional differences. While camping in Boston’s Harvard Yard, a group of New England ex-seamen from Marblehead got into a brawl with some Virginian rifleman. That the Marblehead men included Blacks might have been one of its causes. The fight consisted of fists and snowballs, not weapons. Eleven-year-old Israel Trask recalled watching as George Washington personally waded into the fray, grabbing two “savage-looking” riflemen by the neck to stop it.

The Continental Army had in its ranks people with secrets. Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, a German who turned the American army into a well-disciplined force during its winter at Valley Forge, was gay. Robert Shurtleff also had something to hide. Joining the Fourth Massachusetts Regiment in 1782, this person was in fact Deborah Sampson, who’d disguised herself as a man. Shot in the thigh during a fight in New York’s Hudson Valley, she extracted the musket ball herself to avoid being outed as a woman. For a year and a half her deception worked.

A lack of discipline was one of its biggest problems, an issue exasperated by regional differences. While camping in Boston’s Harvard Yard, a group of New England ex-seamen from Marblehead got into a brawl with some Virginian rifleman. That the Marblehead men included Blacks might have been one of its causes. The fight consisted of fists and snowballs, not weapons. Eleven-year-old Israel Trask recalled watching as George Washington personally waded into the fray, grabbing two “savage-looking” riflemen by the neck to stop it.

The Continental Army had in its ranks people with secrets. Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, a German who turned the American army into a well-disciplined force during its winter at Valley Forge, was gay. Robert Shurtleff also had something to hide. Joining the Fourth Massachusetts Regiment in 1782, this person was in fact Deborah Sampson, who’d disguised herself as a man. Shot in the thigh during a fight in New York’s Hudson Valley, she extracted the musket ball herself to avoid being outed as a woman. For a year and a half her deception worked.

8 While in Philadelphia she became ill and fell unconscious at a hospital at which her secret was discovered. She was nonetheless honorably discharged in 1783—the only American woman in the war with this distinction. In 1785 she had married Benjamin Gannet. In 1797, Harman Mann published The Female Review: or, Memoirs of an American Young Lady telling about her exploits. After her death, her husband received her military pension. It should be noted that a neighbor’s diary discovered in 2019 cast doubt on some of her supposed exploits, such as her being at the Battle of Yorktown (she joined several months after this event), but it doesn’t disprove that she fought in the Continental Army.

While a woman openly joining the Continental Army would’ve been rejected, it happily accepted teenage boys. Fifteen-year-old Joseph Plumb Martin from Connecticut was one. He joined up in New York in June 1776 to show that he was a Patriot. He saw his first fighting at Battle of Brooklyn Heights at which he found it not all romantic. He recalled, “the horrors of battle … [that] presented themselves to my mind in all their hideousness.”

Although Washington lost New York City and never retook it, this didn’t mean the British controlled the whole colony of New York. Taking New York City was the first step of a plan to cut New England off from the rest of the colonies by controlling its three most important waterways: the Hudson River, Lake Champlain, and Lake George. General John Burgoyne drafted a plan to complete this task. For it work, Burgoyne would head south out of Canada to take both the lakes and the Hudson River, while Brigadier General Barry St. Leger would head through the Mohawk Valley, eventually meeting with his commander’s force. Sir William Howe, in overall command the British army in the colonies, was supposed to head north out of New York City and meet with Burgoyne as well, but his force went south to take Philadelphia instead.

While a woman openly joining the Continental Army would’ve been rejected, it happily accepted teenage boys. Fifteen-year-old Joseph Plumb Martin from Connecticut was one. He joined up in New York in June 1776 to show that he was a Patriot. He saw his first fighting at Battle of Brooklyn Heights at which he found it not all romantic. He recalled, “the horrors of battle … [that] presented themselves to my mind in all their hideousness.”

Although Washington lost New York City and never retook it, this didn’t mean the British controlled the whole colony of New York. Taking New York City was the first step of a plan to cut New England off from the rest of the colonies by controlling its three most important waterways: the Hudson River, Lake Champlain, and Lake George. General John Burgoyne drafted a plan to complete this task. For it work, Burgoyne would head south out of Canada to take both the lakes and the Hudson River, while Brigadier General Barry St. Leger would head through the Mohawk Valley, eventually meeting with his commander’s force. Sir William Howe, in overall command the British army in the colonies, was supposed to head north out of New York City and meet with Burgoyne as well, but his force went south to take Philadelphia instead.

9 Burgoyne brought with him a contingent of Hessian mercenaries. This appellation was applied because the biggest number of these Germanic people came from Hesse-Cassel and Hesse-Hanau. Other so-called Hessians came from Anhalt-Zerbst, Anspach-Beyreuth, Brunswick, and Waldeck. That King George III hired mercenaries from the Germanic states is no surprise considering that his father and grandfather were both born and raised in another Germanic principality, the Electorate of Hanover.

Burgoyne gave command of the Hessians to Major General Friedrich Adolf Riedesel zu Eisenbach, a German baron. They belonged to the Brunswick Corp. The baron brought with him his wife, Baroness Frederika Charlotte Riedesel and their three children, one of whom was an infant. She was one of about 1,000 woman accompanying Burgoyne’s army. The baroness kept a diary of her travels during the campaign and her fate afterwards.

Burgoyne began the campaign in June 1777. He did well until reaching the village of Saratoga. Here an American army under the command of General Horatio Gates had fortified the Bemis Heights as well as creating a defensive wall about a mile away. Burgoyne launched three columns at the Americans only to be repelled. Expecting the reinforcement of General Henry Clinton and his men, Burgoyne decided to dig in. Terrible fighting ensued. In the basement of a building, Baroness Frederika established a shelter for the woman, children and wounded soldiers.

Clinton never arrived. Low on food and supplies, Burgoyne surrendered on October 17. The baron and baroness were held as prisoners of war until 1783. The Patriot victory at Saratoga convinced the French to openly support the rebels, and with that came supplies and, more importantly for the Battle of Yorktown, French naval ships. Although there would be many setbacks along the way, the Americans ultimately prevailed.🕜

Burgoyne gave command of the Hessians to Major General Friedrich Adolf Riedesel zu Eisenbach, a German baron. They belonged to the Brunswick Corp. The baron brought with him his wife, Baroness Frederika Charlotte Riedesel and their three children, one of whom was an infant. She was one of about 1,000 woman accompanying Burgoyne’s army. The baroness kept a diary of her travels during the campaign and her fate afterwards.

Burgoyne began the campaign in June 1777. He did well until reaching the village of Saratoga. Here an American army under the command of General Horatio Gates had fortified the Bemis Heights as well as creating a defensive wall about a mile away. Burgoyne launched three columns at the Americans only to be repelled. Expecting the reinforcement of General Henry Clinton and his men, Burgoyne decided to dig in. Terrible fighting ensued. In the basement of a building, Baroness Frederika established a shelter for the woman, children and wounded soldiers.

Clinton never arrived. Low on food and supplies, Burgoyne surrendered on October 17. The baron and baroness were held as prisoners of war until 1783. The Patriot victory at Saratoga convinced the French to openly support the rebels, and with that came supplies and, more importantly for the Battle of Yorktown, French naval ships. Although there would be many setbacks along the way, the Americans ultimately prevailed.🕜