McCook House Civil War Museum

McCook House

Inside the McCook House Civil War Museum

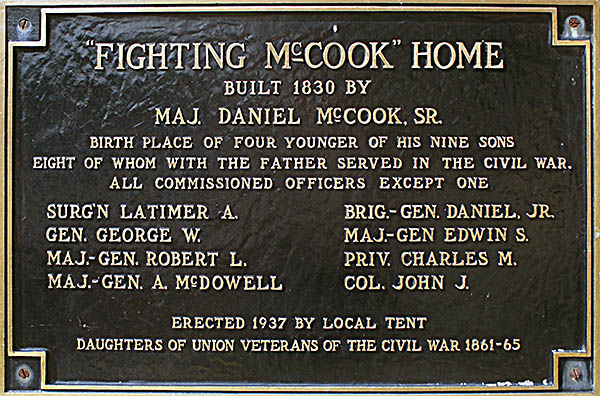

The McCook House’s original owner, Daniel McCook, moved to Carrollton in 1832 and into the house sometime in 1837, and not in 1830 as the plaque beside its main entrance erroneously reports. During the twenty-one years he and his family lived here, they had a profound impact both on the town and the county in which it stands. The McCook family become known as the “Fighting McCooks” because a large portion of two consecutive generations of its men served in the American military. The family consisted of three branches headed by brothers Daniel, John, and George. These patriarchs oversaw the “Tribe of Dan,” the “Tribe of John,” and the “Tribe of George.”

John’s son Henry Christopher was a trained minister born in 1837. Despite being a man of the cloth, he helped to raise the 41st Regiment of Illinois Volunteers. Commissioned as a captain in Company A on August 7, 1861, he became its chaplain. His military career didn’t last long. The next year he became a minster for the Presbyterian Church in Clinton, Illinois. In 1870 he moved to Pennsylvania to take up the post of pastor of the Seventh Presbyterian Church of Philadelphia.

A bit of a renaissance man, he not only oversaw the merger of the Sixth and Seventh Presbyterian Churches in 1873, he designed some of the architectural features for the combined congregations’ new Tabernacle Presbyterian Church. He was also a noted scientist. Over the years he penned a number of scientific papers and books including page turners such as The Natural History of the Agricultural Ant of Texas, American Spiders and Their Spinning Work, and Ant Communities and How They Are Governed: A Study in Natural Civic.

He never abandoned his connection with the U.S. military. When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, he was a reserve chaplain for the Pennsylvania Volunteer’s Regiment. From this he was detached for relief work in Cuba with the National Relief Commission, an organization with the goal of bettering hospitals and improving care for the sick and wounded. In his spare time he worked to identify graves of Americans who died on the island, this venture resulting in still another book, The Martial Graves of our Fallen Heroes in Santiago de Cuba. His own grave can be found in Woodlands Cemetery in Philadelphia into which he was put after his death in Devon, Pennsylvania, on October 31. 1911.

A bit of a renaissance man, he not only oversaw the merger of the Sixth and Seventh Presbyterian Churches in 1873, he designed some of the architectural features for the combined congregations’ new Tabernacle Presbyterian Church. He was also a noted scientist. Over the years he penned a number of scientific papers and books including page turners such as The Natural History of the Agricultural Ant of Texas, American Spiders and Their Spinning Work, and Ant Communities and How They Are Governed: A Study in Natural Civic.

He never abandoned his connection with the U.S. military. When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, he was a reserve chaplain for the Pennsylvania Volunteer’s Regiment. From this he was detached for relief work in Cuba with the National Relief Commission, an organization with the goal of bettering hospitals and improving care for the sick and wounded. In his spare time he worked to identify graves of Americans who died on the island, this venture resulting in still another book, The Martial Graves of our Fallen Heroes in Santiago de Cuba. His own grave can be found in Woodlands Cemetery in Philadelphia into which he was put after his death in Devon, Pennsylvania, on October 31. 1911.

Inside the McCook House Civil War Museum

Another of Daniel’s sons, Edwin Stanton, survived the Civil War but didn’t avoid a violent death. Considered the family’s hothead, he was born in Carrollton in 1837 and educated at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. Despite being trained as a seaman, when war broke out he decided to enter the army instead. He organized a company of men that joined the 31st Illinois Voluntary Infantry commanded by his friend Colonel John A. Logan. Badly wounded during Grant’s attack on Fort Donelson on the border of Tennessee and Kentucky, Edwin recovered and went on to take command of Logan’s regiment. He fought in several major campaigns, including Sherman’s March to the Sea. He became a brigadier general and was made a brevet major general.

In February 1872 Edwin was appointed Secretary of the Territory of Dakota, and in April 1873 became its acting governor. On September 11 of that same year he went to the city of Yankton, the territory’s capital, to help resolve a conflict between it and the Dakota Southern Railroad Company. At a meeting in the city’s courthouse, Peter P. Wintermute proposed a resolution that expressed no confidence in the railroad and its management. This went nowhere, so he headed to the nearby St. Charles Hotel for a drink.

Here he saw Edwin, a known ally of the Dakota Southern, and he asked the acting governor if he had a cigar, or, according to a different source, five cents to buy one. Edwin had no such sum on his person and wouldn’t give Wintermute it anyway. Wintermute already disliked Edwin because he believed the acting governor had prevented him from becoming a U.S. marshal. Wintermute said he could whip Edwin, who laughed at that. Infuriated, Wintermute spewed more threats that included shooting him. When he called Edwin a “Goddamn dirty puppy,” Edwin slapped him in the face several times, jerked him about, then pushed his face into a spittoon.

In February 1872 Edwin was appointed Secretary of the Territory of Dakota, and in April 1873 became its acting governor. On September 11 of that same year he went to the city of Yankton, the territory’s capital, to help resolve a conflict between it and the Dakota Southern Railroad Company. At a meeting in the city’s courthouse, Peter P. Wintermute proposed a resolution that expressed no confidence in the railroad and its management. This went nowhere, so he headed to the nearby St. Charles Hotel for a drink.

Here he saw Edwin, a known ally of the Dakota Southern, and he asked the acting governor if he had a cigar, or, according to a different source, five cents to buy one. Edwin had no such sum on his person and wouldn’t give Wintermute it anyway. Wintermute already disliked Edwin because he believed the acting governor had prevented him from becoming a U.S. marshal. Wintermute said he could whip Edwin, who laughed at that. Infuriated, Wintermute spewed more threats that included shooting him. When he called Edwin a “Goddamn dirty puppy,” Edwin slapped him in the face several times, jerked him about, then pushed his face into a spittoon.

Edwin Stanton McCook

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Battle of Chickamauga

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Sewing Machine and Spinning Wheel

Colt Revolver

Wintermute went to his hotel room, retrieved a gun, and returned to the courthouse in anticipation of the acting governor making an appearance. Although warned of Wintermute’s plan by a bystander, Edwin nonetheless went. Sure enough, Wintermute shot him when he arrived, but this did not stop Edwin from attacking his would-be assassin. A struggle ensued that resulted in the overturning of a stove, a drum, and chairs. It ended with Edwin atop Wintermute on the floor. The latter still had his gun and fired it twice more into Edwin. After being pulled apart, Edwin grabbed Wintermute and started throwing him through a window before bystanders stopped him. Mortally wounded, he was taken to his hotel room. Unafraid of death, he finished up some affairs and passed on, leaving behind a wife and child.

A month later in the same courtroom where the killing had occurred, a grand jury indicted Wintermute on manslaughter, not murder as expected. Infuriated, the new acting governor, Oscar Whitney, who also happened to be Edwin’s father-in-law, transferred the presiding judge, Alanson Barnes, far away. He replaced him with Judge Peter C. Shannon, who oversaw over a second grand jury that did indict Wintermute for murder. The trial began in May 1874 but, because he could afford and had retained the best lawyers, Wintermute was found guilty of the lesser offense of manslaughter. Sentenced to ten years in the Iowa Penitentiary, an appeal all the way to the territorial supreme court got his conviction reversed. A third grand jury indicated him for murder. The new trial, held in Vermillion, resulted in Wintermute’s acquittal.

Over all, fifteen men of the McCook family served in the Civil War in some capacity, and of those, four died. Hanging on one of the museum’s walls is the excellent painting The Fighting McCooks. Painted by Charles T. Webber in 1871, the museum possesses a copy in oil that has more details than the original. It contains Daniel and all his sons who served. An artistic triumph, it is worth gazing upon for a minute or two because it humanizes these men whose lives the museum celebrates. Although long gone from Carrollton, the family’s descendants have donated many of its precious heirlooms to the museum.

A month later in the same courtroom where the killing had occurred, a grand jury indicted Wintermute on manslaughter, not murder as expected. Infuriated, the new acting governor, Oscar Whitney, who also happened to be Edwin’s father-in-law, transferred the presiding judge, Alanson Barnes, far away. He replaced him with Judge Peter C. Shannon, who oversaw over a second grand jury that did indict Wintermute for murder. The trial began in May 1874 but, because he could afford and had retained the best lawyers, Wintermute was found guilty of the lesser offense of manslaughter. Sentenced to ten years in the Iowa Penitentiary, an appeal all the way to the territorial supreme court got his conviction reversed. A third grand jury indicated him for murder. The new trial, held in Vermillion, resulted in Wintermute’s acquittal.

Over all, fifteen men of the McCook family served in the Civil War in some capacity, and of those, four died. Hanging on one of the museum’s walls is the excellent painting The Fighting McCooks. Painted by Charles T. Webber in 1871, the museum possesses a copy in oil that has more details than the original. It contains Daniel and all his sons who served. An artistic triumph, it is worth gazing upon for a minute or two because it humanizes these men whose lives the museum celebrates. Although long gone from Carrollton, the family’s descendants have donated many of its precious heirlooms to the museum.

After the McCook family left town in 1853, their house served for many years as the Geo. J. Butler General Store. It was slated for demolition in 1947 until the Carrollton Historical Society intervened, prompting the State of Ohio to purchase it. In 1981 the Society in partnership with Ohio History Central began administering the property. Although a decent sized house, it is not excessively massive, making one wonder why its architect decided to put into it no less than ten doors. Paint once covered its soft bricks, but the decision to remove this has exposed them to the elements, causing decay. Ohio History Central, once known as the Ohio Historical Society (and a superior name so far as I’m concerned), ought to consider applying a couple coats of paint to prevent further erosion. There is far more about the McCook family in my book Hidden History of Northeast County in the chapter about Carroll County.

Although much of the McCook House is about the family who once lived here, civil War enthusiasts will really enjoy the its many artifacts from the Civil War. Here one can see the Henry Repeating Rifle carried by Daniel, a bone ring carved by a prisoner of war at the notorious Andersonville prison camp, and the canteen of J.M. Potts who was in the Eightieth Regiment of Ohio Infantry and served from 1861 to 1865. Medical tools and a case that belonged to Dr. Jasper Tope give grisly testament to the sort of treatment the wounded received.

One of the more intriguing items is a tree trunk embedded with cannonballs from the Battle of Chickamauga Creek. Fought from September 19 to 21, 1863, it occurred in Georgia along the Chickamauga Creek at which a force under Union general William Rosecrans’ Army of the Cumberland clashed with one under Confederate general Braxton Bragg, the latter of whom was reinforced by General James Longstreet. The numbers involved were staggering. Rosecrans’ force of 50,000 fought Bragg’s 60,000, and the latter’s army nearly crumbling under an assault by Longstreet. The Union force rallied under General George Henry Thomas and made an orderly retreat.

Beyond the Civil War, the museum has exhibits about Carroll County’s history. Examples include a reproduction of a doctor’s office from about 1850, a sewing machine from that same year used by Mrs. Jane Bothwell Shepherd of Washington Township, and a case filled with the front pages of newspapers covering important milestones in American history. Also found here is a Chickering piano that defies being tuned because its strings are set side to side instead of the standard front to back.🕜

Although much of the McCook House is about the family who once lived here, civil War enthusiasts will really enjoy the its many artifacts from the Civil War. Here one can see the Henry Repeating Rifle carried by Daniel, a bone ring carved by a prisoner of war at the notorious Andersonville prison camp, and the canteen of J.M. Potts who was in the Eightieth Regiment of Ohio Infantry and served from 1861 to 1865. Medical tools and a case that belonged to Dr. Jasper Tope give grisly testament to the sort of treatment the wounded received.

One of the more intriguing items is a tree trunk embedded with cannonballs from the Battle of Chickamauga Creek. Fought from September 19 to 21, 1863, it occurred in Georgia along the Chickamauga Creek at which a force under Union general William Rosecrans’ Army of the Cumberland clashed with one under Confederate general Braxton Bragg, the latter of whom was reinforced by General James Longstreet. The numbers involved were staggering. Rosecrans’ force of 50,000 fought Bragg’s 60,000, and the latter’s army nearly crumbling under an assault by Longstreet. The Union force rallied under General George Henry Thomas and made an orderly retreat.

Beyond the Civil War, the museum has exhibits about Carroll County’s history. Examples include a reproduction of a doctor’s office from about 1850, a sewing machine from that same year used by Mrs. Jane Bothwell Shepherd of Washington Township, and a case filled with the front pages of newspapers covering important milestones in American history. Also found here is a Chickering piano that defies being tuned because its strings are set side to side instead of the standard front to back.🕜

Daniel McCook, Sr. Photographed by Griswold & Howard. Ca. 1860.

Ohio Memory

Ohio Memory