Entrance

A lamp and radio (oh my).

Egyptian Hall

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

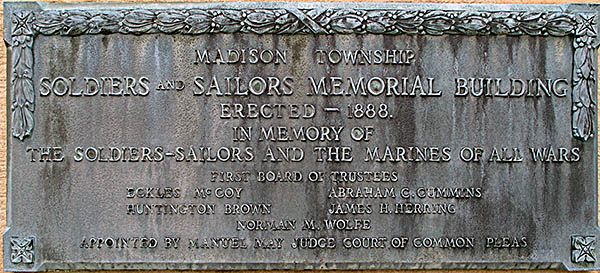

The Mansfield Memorial Museum is the oldest museum in Richland County and is housed in a structure constructed in 1888 called the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Building. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Ohio built thirteen memorial buildings in honor of soldiers and sailors. The first constructed was this one, and it’s also the last standing that is still being used for its original purpose. Ohio stopped building memorial buildings after World War I when the VFW and American Legion began erecting halls in which veterans could meet.

It was here on the second floor that the Civil War veterans’ association called the Grand Army of the Republic met. The Memorial Library Association (now the Mansfield/Richland County Library) installed itself in the first floor where it stayed until 1908. On the third floor was the Mansfield Memorial Museum, which was founded by Edward Wilkinson, who served as its first full time curator until July 18, 1905. During his tenure he labeled much of the collection and built the glass cabinets in which many artifacts are still displayed. Under his curatorship it became one of the best museums in the Midwest.

Wilkinson was well known in the nineteenth century scientific community for his collection of amphibians and reptiles that he’d gathered from the Mexican state of Chihuahua. Born in Mansfield in 1846, his first career was that of sheet metal worker from which he took a break to fight in the Civil War. In 1873 his brother invited him to work in Chihuahua at the mine he ran. During his two years there, Wilkinson collected many specimens, returning in 1885 to find more.

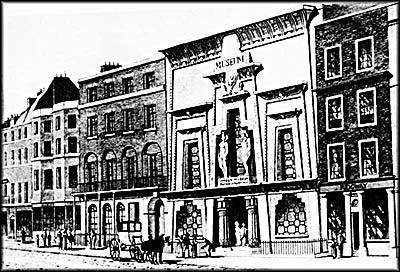

He along with several others, including Dr. J.R. Craig, combined their personal collections to create the Mansfield Memorial Museum, which opened its doors on October 12, 1891. Founding a museum using one’s own personal collection was not unusual in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. One example of this is Egyptian Hall in London. Located on the southern side of Piccadilly Circus, it was built in 1812 and, as its name suggests, looked like an Egyptian tomb complete with Hieroglyphics that no one could read at the time. G.F. Robinson built this edifice for a staggering £16,000, a sound investment as it turned out.

Wilkinson was well known in the nineteenth century scientific community for his collection of amphibians and reptiles that he’d gathered from the Mexican state of Chihuahua. Born in Mansfield in 1846, his first career was that of sheet metal worker from which he took a break to fight in the Civil War. In 1873 his brother invited him to work in Chihuahua at the mine he ran. During his two years there, Wilkinson collected many specimens, returning in 1885 to find more.

He along with several others, including Dr. J.R. Craig, combined their personal collections to create the Mansfield Memorial Museum, which opened its doors on October 12, 1891. Founding a museum using one’s own personal collection was not unusual in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. One example of this is Egyptian Hall in London. Located on the southern side of Piccadilly Circus, it was built in 1812 and, as its name suggests, looked like an Egyptian tomb complete with Hieroglyphics that no one could read at the time. G.F. Robinson built this edifice for a staggering £16,000, a sound investment as it turned out.

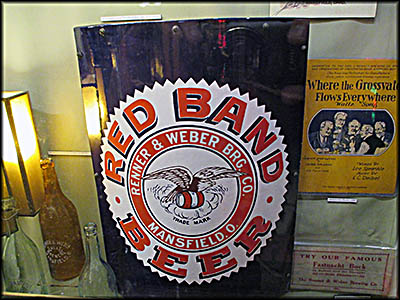

This exhibit highlights the many breweries Mansfield once had.

Mansfield Memorial Museum

Purpose built as a natural history museum, some of its first items on display included a lion, giraffe, and elephant, and birds, all stuffed. It also had art, fossils, and weapons. Its core collection came from items William Bullock had amassed over thirty years of travel in Central America. Beyond his contribution, the museum also drew on the collections of Sir Aston Lever and the Litchfield Museum. The museum’s popularity peaked in 1816 when it put Napoleon’s carriage on display. This attracted 10,000 people daily. In 1819 its collection was auctioned off. After that the building was used primarily as a theater and exhibition hall until its demolition in 1903.

One of the first things a visitor to the Mansfield Memorial Museum will see is the Daisy Barker Thomas/Corley Mansfield/African American Collection that an information sign proudly described as “the largest Mansfield[-]related African-American Collection [sic] known to exist.” Most of it is inside a glass case with some items hanging on the wall. Many of the photos lacked labels, though how much good they would do is questionable considering how hard it was to see through the thick, distorting glass.

Upstairs one will find a large collection of model planes made by the Air National Guard between 1964 and 1987 that complement a smaller collection of model tanks. If models are not to your liking (and I can’t say I have much interest in them), the second floor is filled with a wide variety of items including dueling pistols, an original pike used in John Brown’s ill-fated raid on Harpers Ferry, razor sharp beheading swords from the Philippines, a cane used by the Native American chief Red Cloud, an Incan cocoa drinking pot, an empty box of Rigby’s Cuban Bound cigars once made in Mansfield (apparently the tobacco wraps came from Cuba), Zulu spears, John Sherman’s suit (he being General William Tecumseh Sherman’s brother), cuttings from two apple trees planted by John Chapman (better known as Johnny Appleseed), and a taxidermized ivory-billed woodpecker, now extinct. All the cases on this floor were built by Wilkinson, giving me the feeling that I was visiting the museum as it looked in the 1890s.

One of the first things a visitor to the Mansfield Memorial Museum will see is the Daisy Barker Thomas/Corley Mansfield/African American Collection that an information sign proudly described as “the largest Mansfield[-]related African-American Collection [sic] known to exist.” Most of it is inside a glass case with some items hanging on the wall. Many of the photos lacked labels, though how much good they would do is questionable considering how hard it was to see through the thick, distorting glass.

Upstairs one will find a large collection of model planes made by the Air National Guard between 1964 and 1987 that complement a smaller collection of model tanks. If models are not to your liking (and I can’t say I have much interest in them), the second floor is filled with a wide variety of items including dueling pistols, an original pike used in John Brown’s ill-fated raid on Harpers Ferry, razor sharp beheading swords from the Philippines, a cane used by the Native American chief Red Cloud, an Incan cocoa drinking pot, an empty box of Rigby’s Cuban Bound cigars once made in Mansfield (apparently the tobacco wraps came from Cuba), Zulu spears, John Sherman’s suit (he being General William Tecumseh Sherman’s brother), cuttings from two apple trees planted by John Chapman (better known as Johnny Appleseed), and a taxidermized ivory-billed woodpecker, now extinct. All the cases on this floor were built by Wilkinson, giving me the feeling that I was visiting the museum as it looked in the 1890s.

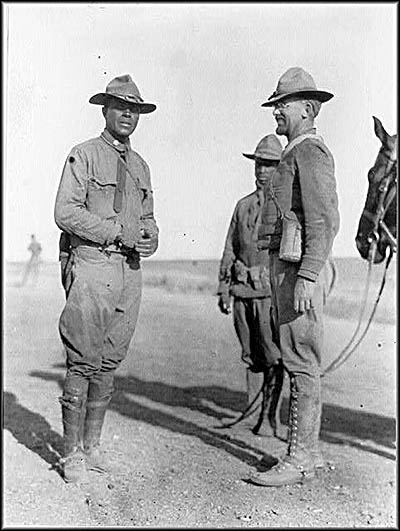

Charles Young (left)

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

The museum has a large collection of model airplanes and tanks.

A few items on display in the museum's collection.

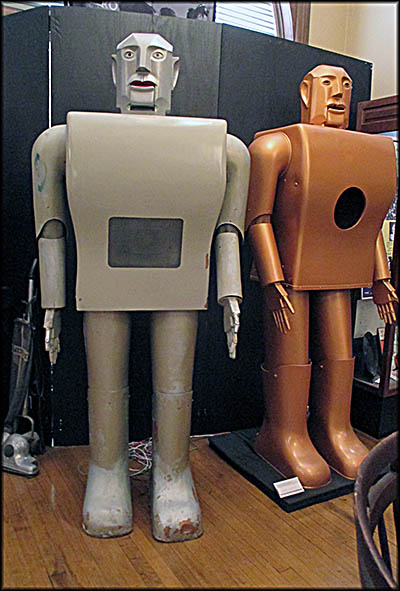

Elektro is the museum's most prized possession. You can learn more about this robot in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio.

The Mansfield Memorial Museum has always and still does serve as a place to memorialize veterans. Artifacts from America’s wars include uniforms, guns, and commendations. One item on the wall that caught my eye was a speech given at a Grand Army of the Republic meeting that outlined the career and achievements of Colonel Charles Young. He was born into slavery on May 12, 1864, in Mays Lick, Kentucky. His father, Gabriel, escaped to join the Union Army in which he served as a private. After the war Gabriel relocated his family to Ripley, Ohio, a town along the Ohio River.

Here Charles attended an integrated high school. Two years after graduating at the top of his class in 1881, his father talked him into taking the entrance exam for West Point. Charles did well and received a nomination from Ohio representative Alphonso Hart. Young reported as a cadet in June 1884, the ninth African-American to do so. Life for white cadets is hard enough, but as a young black man in an era when racial integration was as rare as gold, he suffered much during his time there. He did well with languages but had trouble with engineering and math. He failed his first year of the latter, forcing him to spend five instead of four years at the academy.

When hazed or harassed, he would sing ballads he composed in English and French, further infuriating some of those doing the taunting. By his final year, Young’s relentless drive and refusal to give up did earn the respect of some of his fellow cadets and even led to a few friendships. He wasn’t allowed to graduate with his class. Found deficient in engineering, he had three months to make it up. The instructor who had failed him, Lieutenant George W. Goethals (who later worked on the Panama Canal) became Young’s tutor. Young passed the course in August 1889, allowing him to graduate and making him the third African-American to be commissioned as a second lieutenant.

His first military service was in Utah and Nebraska with the Ninth U.S. Calvary, known informally as the mostly all-black “Buffalo Soldiers.” Next he was assigned to Wilberforce University in Dayton, Ohio, to teach tactics and military science. Here he befriended classics professor W.E.B. Du Boise. Wilberforce University, named after abolitionist William Wilberforce, had been established in 1856 by the Methodist Episcopal Church with the mandate of educating African-Americans. The major decline in attendance because of the Civil War caused it to close in 1862, but fortunately the African Methodist Episcopal Church took over in 1863. It was a private institution until 1887 when the State of Ohio began contributing funds.

When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, Ohio governor Asa S. Bushnell made Young a brevet major and commander of the all-black Ninth Battalion Ohio Volunteers, which never left the shores of the United States but did give Young experience as a commander. After the war he went back into the regular army as a first lieutenant. In 1901 he was made captain, the army’s first African-American to achieve that rank. He was stationed on the island of Samar in the Philippines to fight the “insurrection” prompted when the United States reneged on giving that nation its independence. Here Young distinguished him in combat. For a man whose race was greatly oppressed before and after Reconstruction, it is a bit odd that he was a firm believer in imperialism.

Here Charles attended an integrated high school. Two years after graduating at the top of his class in 1881, his father talked him into taking the entrance exam for West Point. Charles did well and received a nomination from Ohio representative Alphonso Hart. Young reported as a cadet in June 1884, the ninth African-American to do so. Life for white cadets is hard enough, but as a young black man in an era when racial integration was as rare as gold, he suffered much during his time there. He did well with languages but had trouble with engineering and math. He failed his first year of the latter, forcing him to spend five instead of four years at the academy.

When hazed or harassed, he would sing ballads he composed in English and French, further infuriating some of those doing the taunting. By his final year, Young’s relentless drive and refusal to give up did earn the respect of some of his fellow cadets and even led to a few friendships. He wasn’t allowed to graduate with his class. Found deficient in engineering, he had three months to make it up. The instructor who had failed him, Lieutenant George W. Goethals (who later worked on the Panama Canal) became Young’s tutor. Young passed the course in August 1889, allowing him to graduate and making him the third African-American to be commissioned as a second lieutenant.

His first military service was in Utah and Nebraska with the Ninth U.S. Calvary, known informally as the mostly all-black “Buffalo Soldiers.” Next he was assigned to Wilberforce University in Dayton, Ohio, to teach tactics and military science. Here he befriended classics professor W.E.B. Du Boise. Wilberforce University, named after abolitionist William Wilberforce, had been established in 1856 by the Methodist Episcopal Church with the mandate of educating African-Americans. The major decline in attendance because of the Civil War caused it to close in 1862, but fortunately the African Methodist Episcopal Church took over in 1863. It was a private institution until 1887 when the State of Ohio began contributing funds.

When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, Ohio governor Asa S. Bushnell made Young a brevet major and commander of the all-black Ninth Battalion Ohio Volunteers, which never left the shores of the United States but did give Young experience as a commander. After the war he went back into the regular army as a first lieutenant. In 1901 he was made captain, the army’s first African-American to achieve that rank. He was stationed on the island of Samar in the Philippines to fight the “insurrection” prompted when the United States reneged on giving that nation its independence. Here Young distinguished him in combat. For a man whose race was greatly oppressed before and after Reconstruction, it is a bit odd that he was a firm believer in imperialism.

At this time the U.S. Army ran the United States’ national parks, and in 1903 Young was assigned to oversee ninety-three black men to administer Sequoia and General Grant Grove (now Kings Canyon) parks. Normally such a posting for an officer was considered insignificant and would thankfully be over in about two years, but as superintendent, Young treated this duty like any other. He ordered firebreaks dug, put a stop to illegal sheep grazing on park land, had fences built around sequoias to protect their roots, and completed work on a road that took visitors to the Giant Forest.

After a return to San Francisco where he married Ada Mills, he went to Haiti and the Dominican Republic as a military attaché. A few postings later he was made military attaché to Liberia where he was prompted to major and oversaw the reorganization of the Liberian Frontier Force and its police. In December 1912 he again saw combat, this time against locals who ambushed his force during which he was shot in the arm. While in Liberia, he came down with blackwater fever, a complication of malaria that nearly killed him. In 1916 he participated in the U.S. Army’s unsuccessful Punitive Expedition into Mexico to catch Pancho Villa led by Brigadier General John J. Pershing.

Because of his excellent service during this venture, Pershing put Young on a list of officers he felt were worthy of a brigade command. In June 1917 the fifty-three-year-old Young was promoted to the rank of colonel, but he didn’t get sent to Europe as expected. Instead he was found medically unfit because of high blood pressure and suspected kidney damage, which he had because of his malaria. Though he, along with the backing of the NAACP, resisted being relieved of duty, he was forced to take medical retirement.

This was likely because a white officer forced to serve under Young grumbled about it to a Mississippi senator, who wrote a letter of complaint to the notoriously racist President Woodrow Wilson. He in turn ordered Secretary of War Newton Baker to investigate. Baker recommended Young be medically retired. Near the end of the war the army suddenly saw fit to recall Young to duty to oversee Camp Grant’s black stevedore regiments in Illinois. After the war he returned to civilian life only to be recalled a second time. He was sent to Liberia to serve as its military attaché once more. He died of kidney disease on January 8, 1922, while on a trip to Nigeria. Buried in Liberia, his body was moved to Arlington National Cemetery and there interred on June 1, 1923.

The museum’s most prized possession is without doubt the robot Elektro. The story of this automaton is told in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio in the Richfield County chapter.🕜

After a return to San Francisco where he married Ada Mills, he went to Haiti and the Dominican Republic as a military attaché. A few postings later he was made military attaché to Liberia where he was prompted to major and oversaw the reorganization of the Liberian Frontier Force and its police. In December 1912 he again saw combat, this time against locals who ambushed his force during which he was shot in the arm. While in Liberia, he came down with blackwater fever, a complication of malaria that nearly killed him. In 1916 he participated in the U.S. Army’s unsuccessful Punitive Expedition into Mexico to catch Pancho Villa led by Brigadier General John J. Pershing.

Because of his excellent service during this venture, Pershing put Young on a list of officers he felt were worthy of a brigade command. In June 1917 the fifty-three-year-old Young was promoted to the rank of colonel, but he didn’t get sent to Europe as expected. Instead he was found medically unfit because of high blood pressure and suspected kidney damage, which he had because of his malaria. Though he, along with the backing of the NAACP, resisted being relieved of duty, he was forced to take medical retirement.

This was likely because a white officer forced to serve under Young grumbled about it to a Mississippi senator, who wrote a letter of complaint to the notoriously racist President Woodrow Wilson. He in turn ordered Secretary of War Newton Baker to investigate. Baker recommended Young be medically retired. Near the end of the war the army suddenly saw fit to recall Young to duty to oversee Camp Grant’s black stevedore regiments in Illinois. After the war he returned to civilian life only to be recalled a second time. He was sent to Liberia to serve as its military attaché once more. He died of kidney disease on January 8, 1922, while on a trip to Nigeria. Buried in Liberia, his body was moved to Arlington National Cemetery and there interred on June 1, 1923.

The museum’s most prized possession is without doubt the robot Elektro. The story of this automaton is told in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio in the Richfield County chapter.🕜