INVENTION OF THE AUTOMOTIVE AUTOMATIC WINDSHIELD WIPER

Copyright © 2022 by Mark Strecker

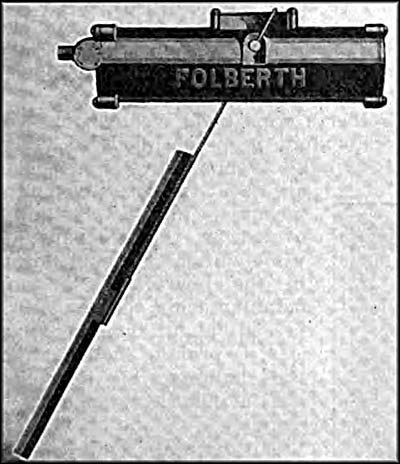

Folberth windshield wiper. The Motor Truck. August 1922.

Digitized by Google.

Digitized by Google.

Attendant wiping a windshield at a gas station in Cairo, Illinois. Photo by John Vachon.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

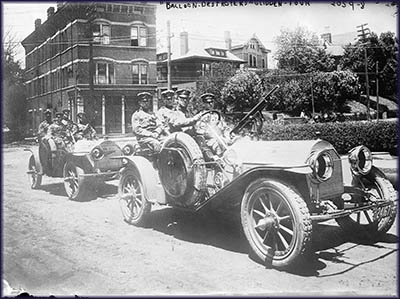

Between 1904 and 1913, the American Automotive Association (AAA) sponsored the Glidden Tour. Each year it had a different route. In 1906, the race had a $50 entry fee and was preceded by a pleasure tour. Only AAA members could participate and racers were limited to 4-passenger touring cars. The pleasure tour started on July 5 and stretched for 1,143 miles between Chicago, Illinois, and Buffalo, New York, the last serving as the starting point for the actual race, which began on July 12. It went for a time into Canada and ended at Bretton Woods Resort in New Hampshire.

During one of the Glidden races, Fred Folberth and his driving partner couldn’t see through their car’s windshield because of pouring rain. Folberth and his driving partner took turns standing on the running board using a linen handkerchief attached to a stick to keep the windshield clear. Doing so was tiring, so they tried dripping a chemical down the windshield to keep the rain off (think Rain-X). Fred thought he had something until the rain stopped and dust stuck to the chemical coating, making it impossible to see through the opaque mess it created. Next he tried an electric wiper, but the car’s engine generated insufficient electricity to power it.

During one of the Glidden races, Fred Folberth and his driving partner couldn’t see through their car’s windshield because of pouring rain. Folberth and his driving partner took turns standing on the running board using a linen handkerchief attached to a stick to keep the windshield clear. Doing so was tiring, so they tried dripping a chemical down the windshield to keep the rain off (think Rain-X). Fred thought he had something until the rain stopped and dust stuck to the chemical coating, making it impossible to see through the opaque mess it created. Next he tried an electric wiper, but the car’s engine generated insufficient electricity to power it.

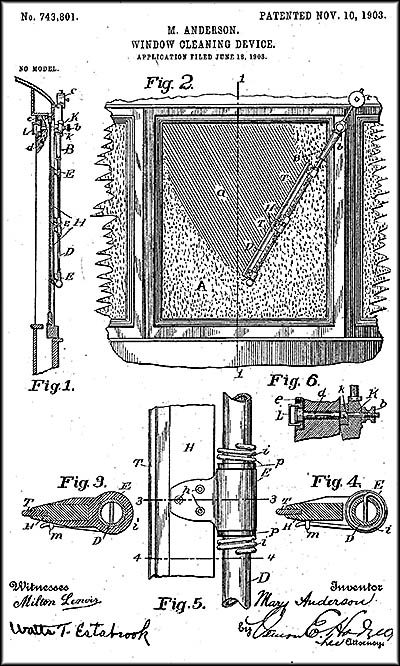

Mary Anderson's Windshield Wiper Patent

Mary Anderson

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Photo from the Glidden Tour. Bain News.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

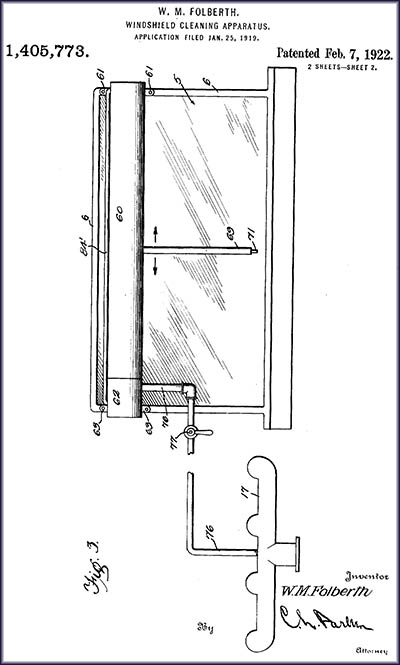

William Folberth's Windshield Wiper Patent

The first patented windshield wiper in the United States came not from a frustrated automobile driver struggling to see during a heavy rainstorm, but rather from a passenger riding in a New York City trolley during a blizzard. She was an Alabama native Mary Anderson, who in 1900 decided to visit New York. Watching the trolley driver repeatedly open a window and stick his hand out to wipe the front window off with a rag gave her the idea of making a hand cranked wiper blade that could be operated from inside the vehicle.

Born at Burton Hill Plantation in Greene County on February 19, 1866, Anderson came from the Southern aristocracy. At the age of four, her father died. Fortunately, the plantation provided a means for her family to live. In 1889 she, her mother Rebecca, and her sister Fannie moved to Birmingham and there had the Fairmont Apartments built as a new means of income. She left home for the first time at the age of 27 to run a vineyard and cattle ranch in Fresno, California, but returned to Birmingham around 1900 to help care for her ailing aunt. After her aunt passed, she and her mother and sister went through some trunks they’d been forbidden to look in, only to find a cache of jewelry and gold, enough to allow them to live quite comfortably from that point forward.

Born at Burton Hill Plantation in Greene County on February 19, 1866, Anderson came from the Southern aristocracy. At the age of four, her father died. Fortunately, the plantation provided a means for her family to live. In 1889 she, her mother Rebecca, and her sister Fannie moved to Birmingham and there had the Fairmont Apartments built as a new means of income. She left home for the first time at the age of 27 to run a vineyard and cattle ranch in Fresno, California, but returned to Birmingham around 1900 to help care for her ailing aunt. After her aunt passed, she and her mother and sister went through some trunks they’d been forbidden to look in, only to find a cache of jewelry and gold, enough to allow them to live quite comfortably from that point forward.

Upon returning home from New York, Mary paid a Birmingham machinist to make a hand-cranked windshield wiper. The design was pretty close to what we use today, although it could be removed when not needed. She received a patent for it on November 10, 1903. So far as anyone knows, she only tried to sell her invention once, and that was to a Canadian firm. It told her it saw no commercial potential for this device, so she gave up trying to market it. She died on June 17, 1953, having split her time between managing Fairmont Apartments and living in her summer home at Monteagle, Tennessee.

Historians seem baffled by her failure to sell her idea and why she gave up so easily. Theories include that drivers probably wouldn’t have wanted to use it because they already had two hands occupied with the steering wheel and gear shifter, or they solved the problem by removing the windshield. More likely it’s because a market for it didn’t exist—yet. Anderson specifically states in her patent that it’s for electric vehicles, probably thinking more about trolleys than cars. Expanding the market to automobiles wouldn’t have helped because there just weren’t enough cars on the road to make it a viable product. In 1903, there were 32,920 cars and trucks registered in the United States. The next year saw an increase of 22,370. It wasn’t until the introduction of the Model T in 1908 and the resulting explosion of auto sales that a real demand for the windshield wiper emerged.

Historians seem baffled by her failure to sell her idea and why she gave up so easily. Theories include that drivers probably wouldn’t have wanted to use it because they already had two hands occupied with the steering wheel and gear shifter, or they solved the problem by removing the windshield. More likely it’s because a market for it didn’t exist—yet. Anderson specifically states in her patent that it’s for electric vehicles, probably thinking more about trolleys than cars. Expanding the market to automobiles wouldn’t have helped because there just weren’t enough cars on the road to make it a viable product. In 1903, there were 32,920 cars and trucks registered in the United States. The next year saw an increase of 22,370. It wasn’t until the introduction of the Model T in 1908 and the resulting explosion of auto sales that a real demand for the windshield wiper emerged.

When Fred Forsyth returned home to Cleveland and told his brother, William, about the problem and the remedies he’d tried that hadn’t worked, William decided to tackle the problem. He and his brother were, after all, inventors of auto parts, including a pump created in 1913 that was powered by the vacuum created by the engine. William’s repeatedly tried and failed to find a way to power an existing wiper blade with car itself. Unable to do so, he gave it rest. While serving on a jury deciding a case involving an accident that occurred because a driver couldn’t see during a rainstorm, he hit upon the idea of powering the wiper by tapping into the vacuum created by the intake manifold.

The final product, perfected in 1919, was marketed as the Folberth Automatic Windshield Wiper. It was attached to the top of a windshield on the driver’s side that had a rubber tube snaking through the dashboard to connect it to the manifold. It was produced in a “fireproof” factory on Lake Avenue in Cleveland and looked very close to what Mary Anderson had invented.

William applied for a patent. When it reached the desk of associate examiner Aubrey D. McFayden at the U.S. patent office, he rejected it outright. He reasoned that since hand-cranked windshield wipers already existed as did the valves Folberth used to make his wiper’s back and forth motion continuous, Folberth had done nothing more than “put two and two together.” Fortunately for Folberth, the decision was reversed by the Board of Appeals. McFayden admitted that he’d made a mistake rejecting the idea. Folberth received his patent on August 16, 1921. The Folberth windshield wiper did have one major drawback. As the car slowed down or climbed a hill, the wipers slowed. Still, it was better than doing it by hand and many a car company adopted it.

The final product, perfected in 1919, was marketed as the Folberth Automatic Windshield Wiper. It was attached to the top of a windshield on the driver’s side that had a rubber tube snaking through the dashboard to connect it to the manifold. It was produced in a “fireproof” factory on Lake Avenue in Cleveland and looked very close to what Mary Anderson had invented.

William applied for a patent. When it reached the desk of associate examiner Aubrey D. McFayden at the U.S. patent office, he rejected it outright. He reasoned that since hand-cranked windshield wipers already existed as did the valves Folberth used to make his wiper’s back and forth motion continuous, Folberth had done nothing more than “put two and two together.” Fortunately for Folberth, the decision was reversed by the Board of Appeals. McFayden admitted that he’d made a mistake rejecting the idea. Folberth received his patent on August 16, 1921. The Folberth windshield wiper did have one major drawback. As the car slowed down or climbed a hill, the wipers slowed. Still, it was better than doing it by hand and many a car company adopted it.

Folberth’s success brought him to the attention of aggressive businessman John R. Oishei, who was also in the windshield wiper business. Born in Buffalo, New York, in 1886, Oishei’s hadn’t started as a seller of wipers. His first career was in theater. Realizing movies would spell the end to traditional theater, he decided to turn to other business ventures. He invested in the Whitmier-Ferris Company for which he invented the paste used to hang the handbills it posted outdoors. Possibly Oishei would’ve stayed in this business had fate not intervened.

On a rainy night in 1916, he found it impossible to see through his windshield, causing him to accidentally hit a bicyclist. While the rider fortunately suffered no serious injury, this incident motivated Oishei to get into the windshield wiper business. He contacted John W. Jepson, the inventor of locally sold hand-operated squeegee windshield wiper and offered to expand its market. Jepson agreed and the device was dubbed the Rain Rubber. Luxury car maker Pierce-Arrow Motor Car Company adopted the device for its vehicles in 1919. The next year Lincoln, Packard and Cadillac followed suit.

Success prompted Oishei to buy Jepson out and put the patent for the squeegee wiper in his own name. He decided to incorporate a new company as Tri-Continental, but upon finding out that name was taken, he changed it to Trico Products. He hired inventors to create new products. He aggressively went after competitors either by suing them for patent infringement or buying them. For three years he badgered Folberth until he gave in and sold out to Trico for $1 million.🕜

On a rainy night in 1916, he found it impossible to see through his windshield, causing him to accidentally hit a bicyclist. While the rider fortunately suffered no serious injury, this incident motivated Oishei to get into the windshield wiper business. He contacted John W. Jepson, the inventor of locally sold hand-operated squeegee windshield wiper and offered to expand its market. Jepson agreed and the device was dubbed the Rain Rubber. Luxury car maker Pierce-Arrow Motor Car Company adopted the device for its vehicles in 1919. The next year Lincoln, Packard and Cadillac followed suit.

Success prompted Oishei to buy Jepson out and put the patent for the squeegee wiper in his own name. He decided to incorporate a new company as Tri-Continental, but upon finding out that name was taken, he changed it to Trico Products. He hired inventors to create new products. He aggressively went after competitors either by suing them for patent infringement or buying them. For three years he badgered Folberth until he gave in and sold out to Trico for $1 million.🕜