INVENTION OF LIFE SAVERS

Copyright © 2022 by Mark Strecker

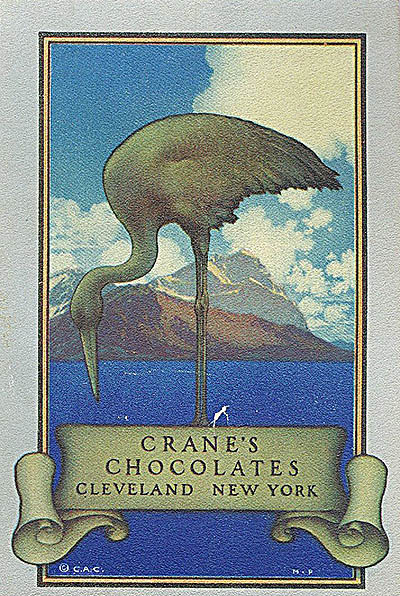

Crane's Chocolates

Courtesy of the Chagrin Falls Historical Society

Courtesy of the Chagrin Falls Historical Society

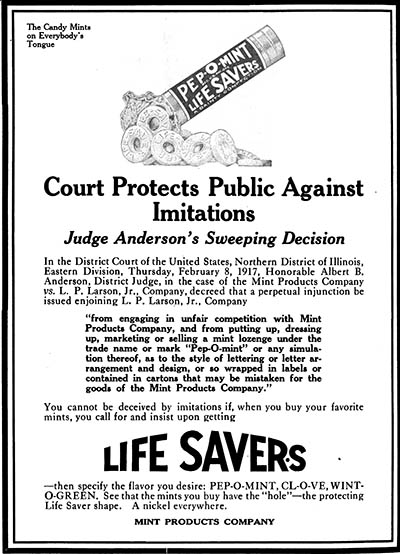

Life Savers ad. Confectioners Gazette. March 10, 1917.

Digitized by Google

Digitized by Google

Edward J. Noble (right) with Assistant to the Secretary of Commerce Harry Hopkins

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Drugstores like this one in Washington, D.C. (1925) would have sold Life Savers.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

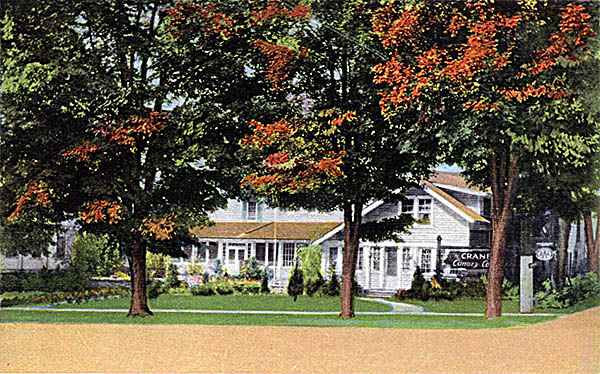

Postcard of Crane's Canary Cottage

Courtesy of the Chagrin Falls Historical Society

Courtesy of the Chagrin Falls Historical Society

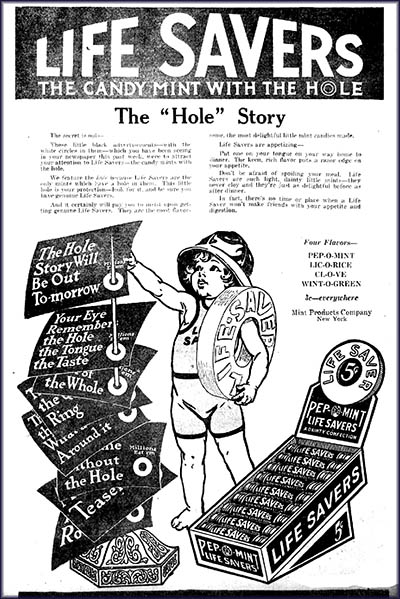

Life Savers trademark illustration. From National Advertising: Notes from the Book of Experience.

Digitized by Google.

Digitized by Google.

Life Savers Ad, 1917

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

The ingredients needed to found the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) included a hot summer, chocolate, and a Cleveland candy maker named Clarence A. Crane. Born in 1875 in Garrettsville, Ohio, Crane first got into the sweet-making business in 1903. In that year he established a maple syrup canning company in Warren, Ohio. Selling this business in 1909, he spent the next two years working as salesman for Nabisco’s Akron branch. In 1911 he moved to Cleveland and there started the Crane Chocolate Company. He ran five retail stores called Crane Company. His signature product was Queen Victoria Chocolate, no doubt so named because he’d purchased the recipe for it in Victoria, British Columbia.

In those day chocolate candy had a major downside: it melted during hot summers in an era when air conditioning was rare, causing sales to drop considerably. A heatwave in the summer of 1912 that fell upon Cleveland was especially bad. It grew so hot and humid that the Cleveland Plain Dealer reported in its July 9 issue that 35 babies had perished because of the heat in just three days. No breeze blew to relieve the suffering in the more densely populated parts of the city, so parks were left open during the night to allow people to sleep there.

In those day chocolate candy had a major downside: it melted during hot summers in an era when air conditioning was rare, causing sales to drop considerably. A heatwave in the summer of 1912 that fell upon Cleveland was especially bad. It grew so hot and humid that the Cleveland Plain Dealer reported in its July 9 issue that 35 babies had perished because of the heat in just three days. No breeze blew to relieve the suffering in the more densely populated parts of the city, so parks were left open during the night to allow people to sleep there.

Crane decided to create a candy resistant to the heat and in 1912 invented a hard peppermint candy he molded using the same mechanism pharmacist’s employed to make round pills. He punched a hole in its center, so it melted in the mouth faster, and marketed his new candy as Crane’s Pep-O-Mint Life Savers with the promise they’d freshen one’s breath. His packaging, a cardboard tube sealed on either end with a beer cap, had a sailor tossing a life preserver to a young woman accompanied by the slogan “For That Stormy Breath.” He trademarked the name Life Savers, which he’d been using since February 28, 1913.

The candy flopped. In the same year he received the trademark, Crane sold it to Edward John Noble, a salesman from New York City who hawked ads for elevated trains and subways. Noble, born in Gouverneur, New York, on August 8, 1882, was a Yale graduate. He bought full rights to Crane’s new candy for $2,900. Not having that much cash personally, he asked his friend, J. Roy Allen, to contribute $1,500 of it.

The candy flopped. In the same year he received the trademark, Crane sold it to Edward John Noble, a salesman from New York City who hawked ads for elevated trains and subways. Noble, born in Gouverneur, New York, on August 8, 1882, was a Yale graduate. He bought full rights to Crane’s new candy for $2,900. Not having that much cash personally, he asked his friend, J. Roy Allen, to contribute $1,500 of it.

The partners started Mint Products Company, which was incorporated in December 1913. What Crane hadn’t realized but Noble soon found out was the cardboard tube in which the Life Savers was packaged leeched its peppermint flavor, leaving behind something that tasted like cardboard and smelled like glue. Small wonder Crane had trouble selling it. This problem nearly forced Mint Products into bankruptcy. Noble solved it by wrapping the candy in tinfoil.

Having left a bad taste in many of it’s buyer’s mouths, Noble needed to reverse poor sales. His initial strategy sounds like something out of a Dickens novel. He placed ads into publications that young people read. If they sold his candy, he offered to give them a portion of the earnings or use that as credit for “premium merchandise” he had on offer. It worked. Sales rose to one million rolls, then up to seven million the next year. Partners Noble and Allen opened a factory to make them in New York City in 1915.

This wasn’t the only secret to Life Savers’ success. Selling for a nickel a roll, Noble convinced barber shops, saloons, cigar stores, restaurants and drugstores to sell his product. He brilliantly pitched the following to them (as reported in a Kiplinger’s Magazine article): “Put Life Savers near the cash register, then be sure every customer gets a nickel with his change and see what happens.” About eighteen months after starting to sell his product, he placed ads on street cars, then in national magazines. The outbreak of World War I halted production. Noble entered the army, serving in the Ordnance Corps.

Having left a bad taste in many of it’s buyer’s mouths, Noble needed to reverse poor sales. His initial strategy sounds like something out of a Dickens novel. He placed ads into publications that young people read. If they sold his candy, he offered to give them a portion of the earnings or use that as credit for “premium merchandise” he had on offer. It worked. Sales rose to one million rolls, then up to seven million the next year. Partners Noble and Allen opened a factory to make them in New York City in 1915.

This wasn’t the only secret to Life Savers’ success. Selling for a nickel a roll, Noble convinced barber shops, saloons, cigar stores, restaurants and drugstores to sell his product. He brilliantly pitched the following to them (as reported in a Kiplinger’s Magazine article): “Put Life Savers near the cash register, then be sure every customer gets a nickel with his change and see what happens.” About eighteen months after starting to sell his product, he placed ads on street cars, then in national magazines. The outbreak of World War I halted production. Noble entered the army, serving in the Ordnance Corps.

Business resumed after the war. In 1923, the company changed its name to Life Savers, Inc. The next year a fruit flavored version was introduced. After thirteen years, Allen sold out for $3,300,000, a 2,200 times return on his original investment. Noble earned a quarter of a million dollars annually.

In 1926, RCA started a subsidiary called the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) to operate two radio networks. In May 1941, the Federal Communications Commission issued new regulations that required NBC to divest from one of these. Parent Company RCA moved all its least desirable affiliates and stations into what it deemed its Blue Network, which Noble purchased in 1943 for $8 million dollars, money he’d made selling Life Savers. He named his new business the American Broadcasting Company.

While Crane failed to make the sort of fortune Life Savers made for Noble, he nonetheless did well for himself. He remained in the candy business for many years with much success. In 1927, he bought two cottages in the village of Chagrin Falls, Ohio. Investing $10,000, he connected them, and added a second story to one so he could live in it. Painted yellow, he called it “Crane’s Canary Cottage.” It served as a restaurant and place where people could come to relax for the day. Here ate such luminaries as Duncan Hines (yes, he’s a real person), Will Rogers and John D. Rockefeller, who once stayed overnight as a guest. After Crane died of a stroke on July 6, 1931, his wife ran the business until World War II.🕜

In 1926, RCA started a subsidiary called the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) to operate two radio networks. In May 1941, the Federal Communications Commission issued new regulations that required NBC to divest from one of these. Parent Company RCA moved all its least desirable affiliates and stations into what it deemed its Blue Network, which Noble purchased in 1943 for $8 million dollars, money he’d made selling Life Savers. He named his new business the American Broadcasting Company.

While Crane failed to make the sort of fortune Life Savers made for Noble, he nonetheless did well for himself. He remained in the candy business for many years with much success. In 1927, he bought two cottages in the village of Chagrin Falls, Ohio. Investing $10,000, he connected them, and added a second story to one so he could live in it. Painted yellow, he called it “Crane’s Canary Cottage.” It served as a restaurant and place where people could come to relax for the day. Here ate such luminaries as Duncan Hines (yes, he’s a real person), Will Rogers and John D. Rockefeller, who once stayed overnight as a guest. After Crane died of a stroke on July 6, 1931, his wife ran the business until World War II.🕜