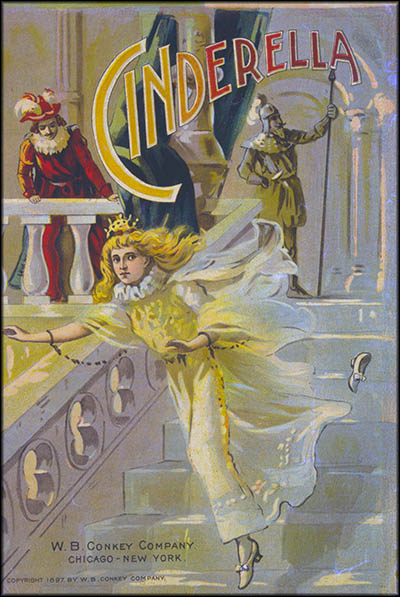

INVENTION OF FOAM-SOLED WASHABLE SLIPPERS

Copyright © 2022 by Mark Strecker

Angle Treads Ad

Chronicling America. Library of Congress

Chronicling America. Library of Congress

Some of the world's best known slippers, all be they fictional, belonged to Cinderella.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

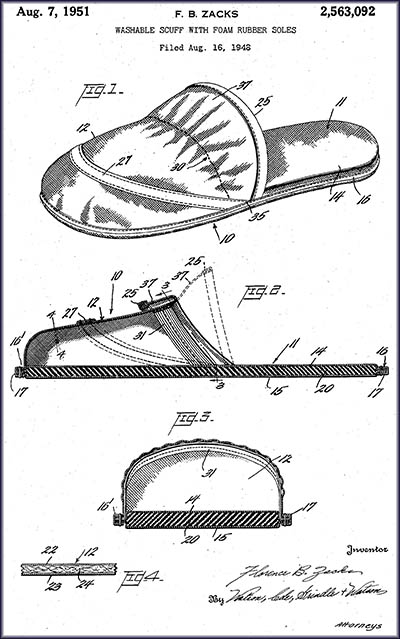

Florence Zacks Merton's Foam-Soled Slipper Patent

Slippers have been around longer than the written word. Chinese courtesans used them as early as 4700 b.c.e. Native Americans, too, wore them in the form of moccasins. Victorians began using them as the type of indoor footwear we wear today. The pope has an ostentatious pair made of satin or silk that are embroidered with gold thread and well decorated. One the best-known pairs of slippers in the world are Cinderella’s fictitious footwear, although glass is hardly the best material if one plans to dance at a ball.

The woman who invented the foam-soled slipper began life as Florence Spurgeon in Philadelphia on November 6, 1911. Her family moved to Camden, New Jersey, when she was a small child. Her parents, Russian Jews, had fled their homeland to escape its pogroms in the late 1890s. Florence’s father took up the trade of door-to-door furniture salesman while her mother ran a boardinghouse. It wasn’t enough income, even with them working. During her childhood, her parents couldn’t even afford to buy her a doll. Three months before graduating from high school, she dropped out so she could help pay the rent. To that end she took a position as a salesclerk at a department store near Camden.

The woman who invented the foam-soled slipper began life as Florence Spurgeon in Philadelphia on November 6, 1911. Her family moved to Camden, New Jersey, when she was a small child. Her parents, Russian Jews, had fled their homeland to escape its pogroms in the late 1890s. Florence’s father took up the trade of door-to-door furniture salesman while her mother ran a boardinghouse. It wasn’t enough income, even with them working. During her childhood, her parents couldn’t even afford to buy her a doll. Three months before graduating from high school, she dropped out so she could help pay the rent. To that end she took a position as a salesclerk at a department store near Camden.

In 1930, at the age of 19, she married Aaron Zacks, who she’d met at the department store. By 1937 the couple had relocated to Hagerstown, Maryland, where they opened a slipcover and drapery store that failed, leaving them $25,000 in debt. In just seven years they paid this off. In 1946 they moved to Columbus where Zacks went to work for a department store.

The militarization of America during World War II prompted women’s fashion to take a decidedly militaristic look. One popular outfit was the double-breasted suit with shoulder pads. The trouble was that the pads needed to be sewn in by hand. When washing the blouse, they had to be removed then sewn back in after the garment dried, else they’d be ruined. Florence saw a possible solution to this tedious process. She came up with a cloth shoulder pad that attached to a bra via an elastic band with a wire support to keep its shape. Calling the product Shoulda-Shams, it sold well enough to prompt Florence and her husband to found the R.G. Barry Company to make them. The company was named after their son and one of their investors. Florence never joined the company as an officer but rather became a “consultant.”

The militarization of America during World War II prompted women’s fashion to take a decidedly militaristic look. One popular outfit was the double-breasted suit with shoulder pads. The trouble was that the pads needed to be sewn in by hand. When washing the blouse, they had to be removed then sewn back in after the garment dried, else they’d be ruined. Florence saw a possible solution to this tedious process. She came up with a cloth shoulder pad that attached to a bra via an elastic band with a wire support to keep its shape. Calling the product Shoulda-Shams, it sold well enough to prompt Florence and her husband to found the R.G. Barry Company to make them. The company was named after their son and one of their investors. Florence never joined the company as an officer but rather became a “consultant.”

After reading an article in Popular Mechanics about the synthetic foam rubber produced at Firestone in Akron, Ohio, during World War II, Florence thought it would be a good idea to make her shoulder pad out of it could then be washed. So she and her husband headed to Akron to visit Firestone to acquire the rights to use it. This suited Firestone, which desired to find new markets for its synthetic foam rubber.

In 1930s, the United States imported half of the world’s natural rubber, most of it produced in South Asia. As a result, rubber companies in the United States actively resisted developing a synthetic version because the existing supply was plentiful and research into the alternative costly. With the outbreak of World War II, access to natural rubber shrunk by a staggering 90 percent. An alarmed President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Rubber Reserve Company in June 1940 to conserve and recycle America’s rubber supply. It wasn’t enough. A synthetic alternative was needed. To facilitate this, the government partnered with B.F. Goodrich, Goodyear, Standard Oil of New Jersey (now Exxon Mobile) and the United States Rubber Company (now Uniroyal). The companies signed an agreement to share patents and research among themselves. The goal was the create something that could be made fast, cheaply, and have about the same duration of use as the real thing.

Synthetic rubber had existed since 1882 when the world’s first was invented by British chemist William Tilden used turpentine, his process taking two weeks to complete. Germany’s Bayer Company created a synthetic rubber in 1912 that the Germans tried to use during World War I. It wasn’t very good and cost too much, so it was abandoned in the latter part of the war. Discoveries of better synthetic rubbers were made, but U.S. companies had no interest in them.

President Roosevelt created the Rubber Survey Committee in August 1942 and he tasked it with making a list of recommendations for how to tackle the creation of synthetic rubber. In just one month it made them. Suggestions included appointing someone to direct the effort as well as the construction of 51 factories to make monomers and polymers, the basic ingredients needed for synthetic rubber. In less than a year, viable synthetic rubber was developed. By 1945 the U.S. produced 920,000 pounds of it annually.

In 1930s, the United States imported half of the world’s natural rubber, most of it produced in South Asia. As a result, rubber companies in the United States actively resisted developing a synthetic version because the existing supply was plentiful and research into the alternative costly. With the outbreak of World War II, access to natural rubber shrunk by a staggering 90 percent. An alarmed President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Rubber Reserve Company in June 1940 to conserve and recycle America’s rubber supply. It wasn’t enough. A synthetic alternative was needed. To facilitate this, the government partnered with B.F. Goodrich, Goodyear, Standard Oil of New Jersey (now Exxon Mobile) and the United States Rubber Company (now Uniroyal). The companies signed an agreement to share patents and research among themselves. The goal was the create something that could be made fast, cheaply, and have about the same duration of use as the real thing.

Synthetic rubber had existed since 1882 when the world’s first was invented by British chemist William Tilden used turpentine, his process taking two weeks to complete. Germany’s Bayer Company created a synthetic rubber in 1912 that the Germans tried to use during World War I. It wasn’t very good and cost too much, so it was abandoned in the latter part of the war. Discoveries of better synthetic rubbers were made, but U.S. companies had no interest in them.

President Roosevelt created the Rubber Survey Committee in August 1942 and he tasked it with making a list of recommendations for how to tackle the creation of synthetic rubber. In just one month it made them. Suggestions included appointing someone to direct the effort as well as the construction of 51 factories to make monomers and polymers, the basic ingredients needed for synthetic rubber. In less than a year, viable synthetic rubber was developed. By 1945 the U.S. produced 920,000 pounds of it annually.

Two years after signing a contract with Firestone, Florence had another idea. Why not make slippers out of foam rubber? That would make them comfortable and washable. This idea she patented in 1948. Over her lifetime she received 18 patents in total. R.G. Barry produced its first line of foam rubber-soled slippers made with quilted chintz fabric in 1947. Called Angel-Treads, a pair cost $1.49. Eleven years later the company introduced the Dearfoams brand. The company’s first slippers were for women, but in the 1950s a men’s line was added. Beyond slippers, R.G. Barry also made insulated pizza boxes, adjustable seat covers and neck pillows. An updated version of the Shoulda-sham received a patent on February 14, 1950. This one lacked the wire for support and used foam rubber for padding. The original wasn’t washable, but the updated version was.

Florence’s first husband died in 1966. Two years later she married Samuel Melton, thus becoming known to history as Florence Zacks Melton. Her second husband was, according to Florence’s obituary in the New York Sun, “an Ohio stainless steel fittings tycoon and philanthropist who served on the boards of many national Jewish charities.” Florence, too, was a great philanthropist. In the early 1980s, she partnered with the Melton Centre for Jewish Education at Hebrew University of Jerusalem to found the Florence Melton Adult Mini-School. Here Jews took two-year courses that taught them about their heritage and religion. Before her death of congestive heart failure on February 8, 2007, she had earned several honorary degrees and, in October 1994, she was inducted into the Ohio Women’s Hall of Fame.🕜

Florence’s first husband died in 1966. Two years later she married Samuel Melton, thus becoming known to history as Florence Zacks Melton. Her second husband was, according to Florence’s obituary in the New York Sun, “an Ohio stainless steel fittings tycoon and philanthropist who served on the boards of many national Jewish charities.” Florence, too, was a great philanthropist. In the early 1980s, she partnered with the Melton Centre for Jewish Education at Hebrew University of Jerusalem to found the Florence Melton Adult Mini-School. Here Jews took two-year courses that taught them about their heritage and religion. Before her death of congestive heart failure on February 8, 2007, she had earned several honorary degrees and, in October 1994, she was inducted into the Ohio Women’s Hall of Fame.🕜