Hancock Historical Museum

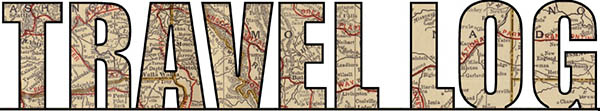

This sketch of Fort Findlay was done by Dr, Albert Lineaweaver based on the recollection of Squire Carlin.

Entrance

Samurai Armor, c. 1603-1868

Exhibit Center

Model of Fort Findlay

Bathtub from the USS Maine

This sergeant's uniform from the War of 1812 is likely a reproduction considering how pristine it looks.

This is the press used to print the Weekly Jefferson, the newspaper in which the "Nasby Letters" first appeared.

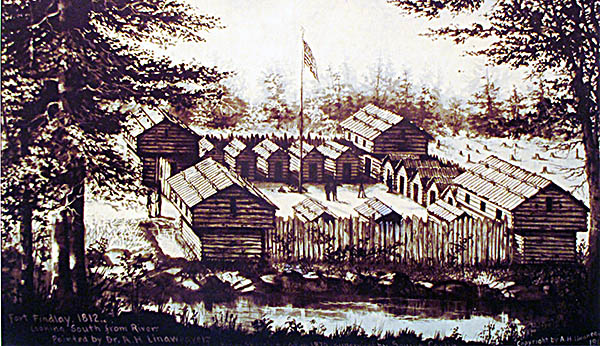

This model of the Columbia House is filled with miniatures of all sorts of things including a mouse!

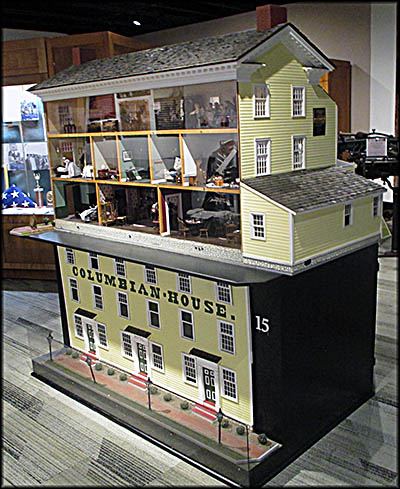

At one point in time Findlay had quite a few opera houses and theaters.

RCA Exhibit

RCA Dog

Cattle Dehorner

Box from Lasalle's Department Store

Pendelton Glass Collection

Bellaire Goblet Company Display

Miller's Luncheonette

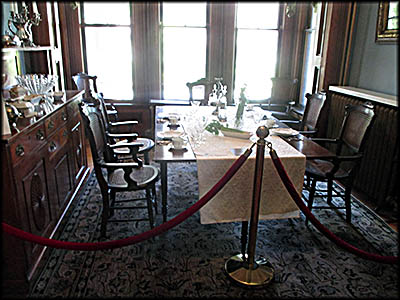

Hull-Flater House Formal Dining Room

Hull-Flater House Informal Parlor

Studebaker Wagon

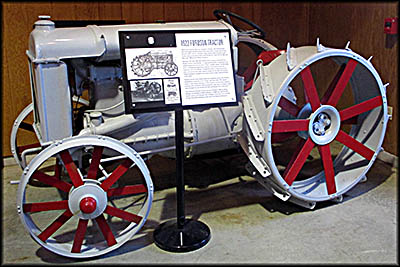

Fordson Tractor

Agricultural Building

Crawford Log House

The one thing I didn’t expect to see at the Hancock Historical Museum in Findlay, Ohio, was a suit of samurai armor. The museum’s focus is on the history of Hancock County in general and Findlay in particular. Its main attraction, the Hull-Flater House, which is made to look as it did during the Victorian Era. Samurais weren’t, so far as I knew, wandering about this part of the world in that time period. So how did it get here? It was originally donated to the Findlay College Museum by a missionary. Upon closing, the college’s collection passed to the Hancock. It’s on display because no curator worth his or her salt is going to let such a fine piece gather dust in storage.

When the museum opened in 1971, it was just the Hull-Flater House, a seventeen-room home built in 1881 in which lived the wealthy Hull family. It was built for Jasper Hull, who founded Farmer’s Bank in 1881. He also cofounded the Findlay Artificial Gas & Light Company and co-owned the Great Karg Well—the one that started the county’s natural gas boom in 1866.

When Jasper’s wife, Mary, died in 1906, her heirs sold the house to Henry Flater. He added a wraparound porch, and converted the house into a duplex to give his son and daughter-in-law a home of their own. Flater ran his fertilizer and seed business from the house’s basement. The Flater family sold the house to Porcelain Products in 1947. Ten years later Porcelain sold it the United Brethren Church, which converted it into offices. It turned the house over to the Hancock Historical Museum Association in 1970. Since then, the museum has expanded to nine buildings with more than 25,000 square feet of space.

Findlay’s history begins with the War of 1812. An information sign says that in the summer of war’s first year, General William Hull marched his army “from the Scioto River to the Maumee River. On this march he began the building of Fort Findlay.” The thirteen men stationed there named it after their regimental commander, Colonel (later Brigadier-General) James Findlay, who marched on, never to see it completed. The fort was abandoned in 1815.

When the museum opened in 1971, it was just the Hull-Flater House, a seventeen-room home built in 1881 in which lived the wealthy Hull family. It was built for Jasper Hull, who founded Farmer’s Bank in 1881. He also cofounded the Findlay Artificial Gas & Light Company and co-owned the Great Karg Well—the one that started the county’s natural gas boom in 1866.

When Jasper’s wife, Mary, died in 1906, her heirs sold the house to Henry Flater. He added a wraparound porch, and converted the house into a duplex to give his son and daughter-in-law a home of their own. Flater ran his fertilizer and seed business from the house’s basement. The Flater family sold the house to Porcelain Products in 1947. Ten years later Porcelain sold it the United Brethren Church, which converted it into offices. It turned the house over to the Hancock Historical Museum Association in 1970. Since then, the museum has expanded to nine buildings with more than 25,000 square feet of space.

Findlay’s history begins with the War of 1812. An information sign says that in the summer of war’s first year, General William Hull marched his army “from the Scioto River to the Maumee River. On this march he began the building of Fort Findlay.” The thirteen men stationed there named it after their regimental commander, Colonel (later Brigadier-General) James Findlay, who marched on, never to see it completed. The fort was abandoned in 1815.

Replica of Squire Carlin's General Store

I learned this in the museum’s Exhibit Center, which is filled with an eclectic mix of displays and artifacts including a bathtub from the USS Maine. A while back I wrote an article about how we Americans have a morbid if not unhealthy obsession with collecting souvenirs. On February 15, 1898, the explosive sinking of the Maine in Havana Harbor sparked the Spanish-American War. Twelve years later, she was raised, refloated, then sank farther out to sea in March 1912. Before she went back to her watery grave, Americans begged for “mementos” from the wreck. Among items salvaged was Captain Charles Sigsbee’s enabled steel bathtub that made its way to Urbana, Ohio. No one there wanted it, so Findlay took it instead.

The tub arrived in there on March 13, 1913, after having been rescued from a chicken coop owned by Urbana’s mayor. At this point the tub was a rusted remnant of its former glory, and within a year someone began storing coal in it. According to a museum information sign, “after patriotic citizens of Findlay and Lima discovered its ignominious fate and raised a ruckus, the tub was placed in a glass case in the Hancock County courthouse for 15 years.” It moved to a new location within the courthouse for another thirty years, then found a home at the aforementioned Findlay College Museum. The Hancock Historical Museum received it along with the rest of the college’s collection when the College Museum closed. As rusty old bathtubs go, it’s not the best specimen of its type, but I did get two paragraphs from it.

Findlay once served as a stop on the Underground Railroad. The man who founded it, African American barber David Adams, had his shop across the street from the Hancock County Court House. He often took escaped slaves from his parents’ house in Urbana to as far as the Perrysburg area from which they could find a ride on a friendly boat or ship heading to Canada. It’s believed Adams shepherded more than fifty slaves who passed through Findlay.

David Ross Locke came to Findlay in 1861 to serve as editor of the Republican newspaper Findlay Weekly Jeffersonian. While here he began writing his satirical “Nasby Letters,” supposedly penned by Reverend Petroleum Vesuvius Nasby. This fellow was a Copperhead—a Democrat who supported the South during the Civil War. He was a lazy, often-drunk, semi-literate idiot whose plans to aid the Confederacy tended to make things worse. When he worked at all, he preached sermons that used Bible quotes to justify slavery. Locke wrote these satirical dispatches, which were filled with spelling and grammatical errors to emphasize Nasby’s ignorance, to make the Confederacy look as bad as possible. When Locke moved to Toledo in 1865 to write for and edit the Toledo Blade, he brought the character with him, using him to skewer those who opposed Reconstruction.

The tub arrived in there on March 13, 1913, after having been rescued from a chicken coop owned by Urbana’s mayor. At this point the tub was a rusted remnant of its former glory, and within a year someone began storing coal in it. According to a museum information sign, “after patriotic citizens of Findlay and Lima discovered its ignominious fate and raised a ruckus, the tub was placed in a glass case in the Hancock County courthouse for 15 years.” It moved to a new location within the courthouse for another thirty years, then found a home at the aforementioned Findlay College Museum. The Hancock Historical Museum received it along with the rest of the college’s collection when the College Museum closed. As rusty old bathtubs go, it’s not the best specimen of its type, but I did get two paragraphs from it.

Findlay once served as a stop on the Underground Railroad. The man who founded it, African American barber David Adams, had his shop across the street from the Hancock County Court House. He often took escaped slaves from his parents’ house in Urbana to as far as the Perrysburg area from which they could find a ride on a friendly boat or ship heading to Canada. It’s believed Adams shepherded more than fifty slaves who passed through Findlay.

David Ross Locke came to Findlay in 1861 to serve as editor of the Republican newspaper Findlay Weekly Jeffersonian. While here he began writing his satirical “Nasby Letters,” supposedly penned by Reverend Petroleum Vesuvius Nasby. This fellow was a Copperhead—a Democrat who supported the South during the Civil War. He was a lazy, often-drunk, semi-literate idiot whose plans to aid the Confederacy tended to make things worse. When he worked at all, he preached sermons that used Bible quotes to justify slavery. Locke wrote these satirical dispatches, which were filled with spelling and grammatical errors to emphasize Nasby’s ignorance, to make the Confederacy look as bad as possible. When Locke moved to Toledo in 1865 to write for and edit the Toledo Blade, he brought the character with him, using him to skewer those who opposed Reconstruction.

After the Civil War, culture came to Findlay in the form of three opera houses in which few, if any, real operas ever played. These venues were mainly home to traveling actors and acting troupes, musicians, Vaudeville acts, and lectures and speeches by prominent people of the day. Findlay’s first one, the Davis Opera House, opened in 1876. Next came the Marvin Opera House. Opening in 1893, “it specialized,” says the information sign, “in Dramatic Entertainment, Light Opera, and Minstrel Shows.” It also provided transport from Fostria, Kenton, Lima and Tiffin so citizens from those places could watch its shows. A wide variety of people appeared here. Celebrities of the day included three-time Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, Booker T. Washington, and Sandra Bernhardt, the last being the equivalent of Taylor Swift showing up.

The Marvin was renamed as the Gillette Theater in 1907. It shut down in 1911 because of safety issues, then reopened in 1916 with its original name. In 1930 it was converted into a movie theater, but that didn’t last long. The next year it burned down in a fire that may have been caused by arson. Fire also twice ravaged the Turner Opera House, the last of the Findlay’s opera houses to be built. It burned in 1920 and 1940.

People could afford such entertainment because Findlay’s many industries offered good jobs. The city’s biggest employer was once the RCA factory. It opened in 1954 with ten employees and started out making television components. When transistors replaced vacuum tubes, it began manufacturing those. In time the plant became the largest producer of transistors in the world, and within ten years from its opening, the number of employees grew to over 1,600. It made other electronic items including integrated circuits, silicon rectifiers, and power transistors. The plant grew to be Hancock County’s largest employer and at its peak, it had a staff of 3,000. This didn’t last. After a gradual decline, it closed for good in the late 1980s.

With industry came retail, which boomed after World War II. By the 1950s, Findlay had five department stores, including J.C. Penny, Lasalle’s, and the locally-owned Patterson’s. J.C. Penny closed its Findlay location in June 2017. In 1985, Lasalle’s was sold to Elder Beerman, a company that went out of business in 2018. Patterson’s opened in 1867. Despite having survived several economic downturns including the Great Depression, by the 1970s it was losing money, and it finally closed in 1982.

The Marvin was renamed as the Gillette Theater in 1907. It shut down in 1911 because of safety issues, then reopened in 1916 with its original name. In 1930 it was converted into a movie theater, but that didn’t last long. The next year it burned down in a fire that may have been caused by arson. Fire also twice ravaged the Turner Opera House, the last of the Findlay’s opera houses to be built. It burned in 1920 and 1940.

People could afford such entertainment because Findlay’s many industries offered good jobs. The city’s biggest employer was once the RCA factory. It opened in 1954 with ten employees and started out making television components. When transistors replaced vacuum tubes, it began manufacturing those. In time the plant became the largest producer of transistors in the world, and within ten years from its opening, the number of employees grew to over 1,600. It made other electronic items including integrated circuits, silicon rectifiers, and power transistors. The plant grew to be Hancock County’s largest employer and at its peak, it had a staff of 3,000. This didn’t last. After a gradual decline, it closed for good in the late 1980s.

With industry came retail, which boomed after World War II. By the 1950s, Findlay had five department stores, including J.C. Penny, Lasalle’s, and the locally-owned Patterson’s. J.C. Penny closed its Findlay location in June 2017. In 1985, Lasalle’s was sold to Elder Beerman, a company that went out of business in 2018. Patterson’s opened in 1867. Despite having survived several economic downturns including the Great Depression, by the 1970s it was losing money, and it finally closed in 1982.

The museum doesn’t neglect mentioning a few former prominent citizens who lived in Findlay. One such person was Squire Carlin. Born in 1801 on Christmas Day in Auburn, New York, his family moved first to Michigan, then to Maumee, Ohio. In 1812 they fled to Urbana to escape the war, passing by Fort Findlay during this trek.

Carlin settled in Findlay in 1826, opening its first general store. Later, in partnership with his brother Parlee, he opened other ventures such as a sawmill and gristmill powered by the Blanchard River—a waterway that goes through Findlay and is a tributary of the Auglaize River. For eighteen years Carlin served as the city’s postmaster and, for eight years, Hancock County’s treasurer. In 1849 he caught gold fever and headed to California. During his two-year trek there and back, his wife Sarah died.

He married Delia Briggs in 1853. He and his brother, Perlee, started Findlay’s Citizen’s Bank in 1854, running it until a financial panic wiped it out in 1878. Carlin also got into railroads and real estate. At the age of ninety he met his end when he fell in a room and broke his hip. You can find his grave in Maple Grove Cemetery.

Judge Chester Pendelton and his wife were prominent citizens in the twentieth century. In the 1940s they began collecting art glass and in thirty years’ time had amassed a collection of 293 pieces that was valued at $25,000 in 1971 (nearly $200,000 today). The couple donated the collection to the museum, which was placed into a case similar to the one they had had in their home.

Carlin settled in Findlay in 1826, opening its first general store. Later, in partnership with his brother Parlee, he opened other ventures such as a sawmill and gristmill powered by the Blanchard River—a waterway that goes through Findlay and is a tributary of the Auglaize River. For eighteen years Carlin served as the city’s postmaster and, for eight years, Hancock County’s treasurer. In 1849 he caught gold fever and headed to California. During his two-year trek there and back, his wife Sarah died.

He married Delia Briggs in 1853. He and his brother, Perlee, started Findlay’s Citizen’s Bank in 1854, running it until a financial panic wiped it out in 1878. Carlin also got into railroads and real estate. At the age of ninety he met his end when he fell in a room and broke his hip. You can find his grave in Maple Grove Cemetery.

Judge Chester Pendelton and his wife were prominent citizens in the twentieth century. In the 1940s they began collecting art glass and in thirty years’ time had amassed a collection of 293 pieces that was valued at $25,000 in 1971 (nearly $200,000 today). The couple donated the collection to the museum, which was placed into a case similar to the one they had had in their home.

On July 2, 1975, someone broke into the museum and purloined ninety of the collection’s pieces. Determined to get them back, the museum offered a reward of $1,000, then increased it to $3,000. The first break in the case occurred on September 10 when museum trustee Harold Corbin received a call at his office from a man asking about the reward. This person later stopped by Corbin’s office and identified himself as David Jurgens. He said he’d restore the stolen pieces for $10,000, paid in unmarked $20 bills. Jurgens warned if the police were contacted, the glass would be broken. The trustees decided to pay up. Sometime later—the information sign isn’t specific about the timeline here—a few pieces of the collection turned up in a cardboard box inside a trash barrel in Green Mills Garden.

Jurgens must’ve watched too many movies or TV shows, because the payment of money on September 11 sounded just like it’d been scripted. At eleven that morning, Jurgens called Corbin and told him to put the money into the same box in which the few pieces had been returned earlier. Corbin picked Jurgens up in front of Miller’s Restaurant, then dropped him off in an alley by the East Crawford Street parking garage. Jurgens made himself scarce.

He was supposed to call the next day to tell Corbin where to find the missing glassware, but it didn’t come. Another museum trustee, Jack Harrinton, noticed that when a man purchased a Cadillac at his dealership for $8,000, he paid in twenties. Not long after, Jurgens called informing Corbin that the remaining glass collection would be found behind Larry’s Barber Shop. Packed in six egg crates, it was all there and undamaged. Now the trustees called the police.

It took them under two hours to find and arrest Jurgens. In exchange for immunity, he gave state’s evidence against Jerry Simon, the “mastermind” behind the heist. He also got to keep the $10,000. Simon was convicted and sent to prison. Jurgens was later convicted for a different burglary and he, too, went to prison.

Jurgens must’ve watched too many movies or TV shows, because the payment of money on September 11 sounded just like it’d been scripted. At eleven that morning, Jurgens called Corbin and told him to put the money into the same box in which the few pieces had been returned earlier. Corbin picked Jurgens up in front of Miller’s Restaurant, then dropped him off in an alley by the East Crawford Street parking garage. Jurgens made himself scarce.

He was supposed to call the next day to tell Corbin where to find the missing glassware, but it didn’t come. Another museum trustee, Jack Harrinton, noticed that when a man purchased a Cadillac at his dealership for $8,000, he paid in twenties. Not long after, Jurgens called informing Corbin that the remaining glass collection would be found behind Larry’s Barber Shop. Packed in six egg crates, it was all there and undamaged. Now the trustees called the police.

It took them under two hours to find and arrest Jurgens. In exchange for immunity, he gave state’s evidence against Jerry Simon, the “mastermind” behind the heist. He also got to keep the $10,000. Simon was convicted and sent to prison. Jurgens was later convicted for a different burglary and he, too, went to prison.

From the Exhibit Center I moved into the Hull-Flater House. Its pretty but looks preserved rather than a place where a family once lived. The biggest shortcoming is its lack of information signs. Which room is the informal parlor and which the formal parlor? I had to guess when writing captions for this travel log’s photos. When I bought the tickets for the museum, the person at the desk handed me a booklet, which I promptly put into my pocket with the idea that I’d read later. I didn’t realize it contained all the details about the house. It would’ve been far more convenient for its content to be on information signs. In this day and age of people taking photos with their phones like crazy, reading a little booklet while going through the house isn’t likely. I know that’s why I didn’t look at it.

I’ve been to enough historic homes made to look like they are in the Victorian Era that it left me with little I hadn’t seen before, such as a dry sink, ice box, and iron cookware. There were some items I’d not seen before, like a moustache cup, which was designed to keep the wax on well-groomed gentlemen’s moustaches from melting. Dinner in the Victorian Age could last up to two hours. You often attended in black tie, and children were normally banned. Stalks of celery decorated the table during informal dinners, and flowers during formal ones.

People who weren’t part of the upper class—that is, most Americans—ate like we do today: the entire family gathered around a table, usually in the kitchen. They didn’t have nannies to tend to the children in the nursery while they ate, servants to bring them food, or houses large enough for a separate formal dining area. The Hull-Flater House, then, is an excellent example of what the home of a wealthy American family looked like during the Victorian Age.

The museum doesn’t neglect covering life for the middle and lower classes. In 1985, it acquired the Crawford Log House, which was built in the 1840s—the dawn of the Victorian age—in which the Metzger family lived in it for many years. Here you can see how the average American family lived, cramped quarters and all. The cabin is far more finished than the temporary ones the earliest pioneers built because it was meant as a permanent home. It has, for example, plank floors.

I’ve been to enough historic homes made to look like they are in the Victorian Era that it left me with little I hadn’t seen before, such as a dry sink, ice box, and iron cookware. There were some items I’d not seen before, like a moustache cup, which was designed to keep the wax on well-groomed gentlemen’s moustaches from melting. Dinner in the Victorian Age could last up to two hours. You often attended in black tie, and children were normally banned. Stalks of celery decorated the table during informal dinners, and flowers during formal ones.

People who weren’t part of the upper class—that is, most Americans—ate like we do today: the entire family gathered around a table, usually in the kitchen. They didn’t have nannies to tend to the children in the nursery while they ate, servants to bring them food, or houses large enough for a separate formal dining area. The Hull-Flater House, then, is an excellent example of what the home of a wealthy American family looked like during the Victorian Age.

The museum doesn’t neglect covering life for the middle and lower classes. In 1985, it acquired the Crawford Log House, which was built in the 1840s—the dawn of the Victorian age—in which the Metzger family lived in it for many years. Here you can see how the average American family lived, cramped quarters and all. The cabin is far more finished than the temporary ones the earliest pioneers built because it was meant as a permanent home. It has, for example, plank floors.

The last place my traveling companion and I visited was the Agricultural Building. Until about 1920, the majority of Americans lived in rural areas, most of them on family farms, and the sort of items they worked with are found here, including the cattle dehorner. This tool resembles huge pliers used to remove horns from cattle. The younger the cow or bull, the less painful it was. The information sign says “dehorning produces more docile cattle that are easier to handle.” It also points out that there are now breeds of hornless cattle you can purchase, so the tool is obsolete.

When you hear the word “Studebaker” you probably think of the now-defunct car company. But it began as a prominent wagon and buggy maker founded by brothers Henry and Clement Studebaker. They were blacksmiths in South Bend, Indiana, and initially made the metal parts for wagons. The California Gold Rush incentivized them to making entire wagons, and during the Civil War they provided the Union with these. The brothers formed the Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing Company in 1868. It made just about every kind of vehicle pulled by horses that existed at the time. One of their wagons is on display in the Agricultural Building.

Also here is a 1922 Fordson tractor made by Henry Ford & Son. While not the first tractor on the market, the Fordson was the first reliable one sold at a price farmers could afford. Although not the sole cause, it was a contributing factor to the migration of Americans from rural to urban areas because it reduced the number of people needed to work on farms. Finding themselves unemployed, former farmhands headed for cities to find work in industry.

There is much to see at this museum. There are three more buildings on the campus I didn’t visit: the Marathon Petroleum Corporation Energy & Transportation Annex (I missed this one), the Dewald-Funk House (it was closed on the day I went), and the Davis Learning Institute (also was closed—here the museum does digital storytelling). The museum also runs the Little Red Schoolhouse on County Road 236, another building I missed.🕜

When you hear the word “Studebaker” you probably think of the now-defunct car company. But it began as a prominent wagon and buggy maker founded by brothers Henry and Clement Studebaker. They were blacksmiths in South Bend, Indiana, and initially made the metal parts for wagons. The California Gold Rush incentivized them to making entire wagons, and during the Civil War they provided the Union with these. The brothers formed the Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing Company in 1868. It made just about every kind of vehicle pulled by horses that existed at the time. One of their wagons is on display in the Agricultural Building.

Also here is a 1922 Fordson tractor made by Henry Ford & Son. While not the first tractor on the market, the Fordson was the first reliable one sold at a price farmers could afford. Although not the sole cause, it was a contributing factor to the migration of Americans from rural to urban areas because it reduced the number of people needed to work on farms. Finding themselves unemployed, former farmhands headed for cities to find work in industry.

There is much to see at this museum. There are three more buildings on the campus I didn’t visit: the Marathon Petroleum Corporation Energy & Transportation Annex (I missed this one), the Dewald-Funk House (it was closed on the day I went), and the Davis Learning Institute (also was closed—here the museum does digital storytelling). The museum also runs the Little Red Schoolhouse on County Road 236, another building I missed.🕜

The steam-powered Buckeye Traction Ditcher was used mainly to dig ditches designed to drain the Great Black Swamp, which was in the northwestern part of Ohio. The machine was patented by James B. Hill of Bowling Green, Ohio, the only major city within the boundries of the former Great Black Swamp.