Museum

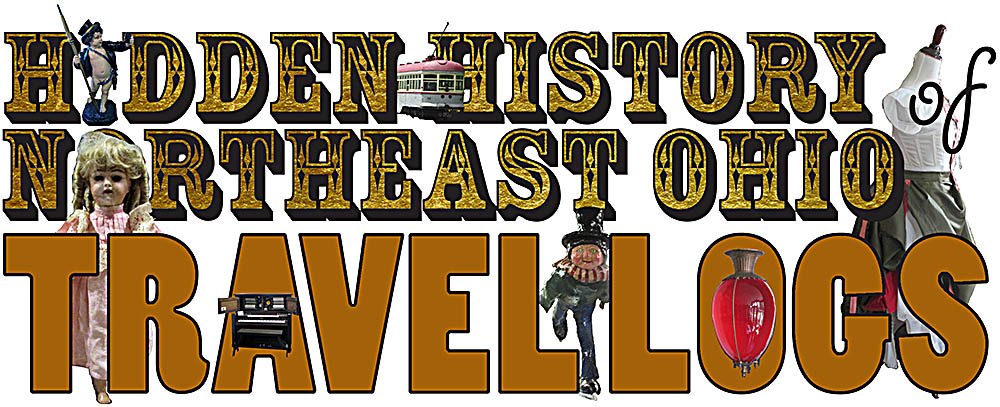

Cabin on the Museum Grounds

Gnadenhutten Museum and Historic Site is the first museum I’ve ever visited located in the middle of an active cemetery. From the outside it looks like a humble cabin that couldn’t possibly hold that much, but this is an optical illusion. Its two rooms are filled with a wide variety of items. In the entry room you will see hundreds of arrowheads and other artifacts created by Ohio’s native inhabitants. Here are scattered remains of the original village that once stood on the same ground as the cemetery, including a few flagstones and a couple shards of glass. Those who destroyed the village, took everything of value they could steal. (The story of the massacre that happened here, core to the museum, is told in my book Hidden History of Northeast Ohio.)

Also on the museum grounds are replicas of the original church and cooper shop, the latter belonging to the villager’s cofounder, Joshua. In addition to making buckets, barrels and other items coopers produced, Joshua also carved gunstocks. During the archeological excavation of the site it was determined the building once had a basement entered via an exterior set of steps. Joshua died in 1775, sparing him from seeing his community destroyed.

The museum does far more than tell the story of the terrible massacre that happened here. It is a historical society that looks at all aspects of the area’s history including a small exhibit about baseball legend Cy Young. Born and raised on a farm near Gilmore, about eleven miles south of Gnadenhutten, his name in full was Denton True Young. In adulthood he was 6’2” and extremely strong as all manual farm workers in that era were wont to be. The museum’s information sign about him showed a photo of the family barn and reported he hung a horse collar over the doorway that he used to practice throwing baseballs through.

He started his baseball career playing with local teams. In 1890 he tried out for the Tri-State League in Canton, Ohio. So shy was he that it took him six attempts before he mustered enough courage to enter the ballpark. The manager of Canton’s team, George Moreland, signed Young up for a monthly salary of $40. His fastballs pounded the grandstand boards, prompting a catcher to give him the nickname “Cyclone.” A sportswriter shortened it to “Cy.” Halfway through the season the Tri-state League collapsed, so Young joined the National League team Cleveland Spiders in August for $300 a year.

Cy played with them until 1898 when the team’s owner, Frank Robison, bought the Cardinals and decided to send his best players to St. Louis, Young among them. That year he made an impressive $2,400. Three years later he departed and joined the Boston Pilgrims, one of the teams belonging to the newly formed American League. The Pilgrims soon changed their name to the Red Sox.

In 1903 Young pitched his first World Series. In 1909 he moved to the Cleveland Indians and in 1911 spent the season’s second half with the Boston Braves. He retired in 1912 and moved to Peoli, about twelve miles south of Gnadenhutten. He lived to be eighty-eight and at the age of eighty-six threw the ceremonial pitch at the 1953 World Series between the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Yankees. Yogi Berra caught the ball.

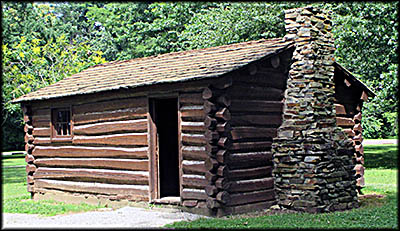

The museum’s interior is filled with life size manikins, mostly Native Americans, that were clearly handmade. This sort of thing is fine when done well, but I’ve found that most museums, especially small ones, rarely have ones that ought to be seen by the public. Most of this museum’s manikins are creepy and amateurish, one notable exception being the excellent one of John Heckewelder—who reformed the town after its destruction—in the backroom. Despite their shortcomings, the manikins are so well integrated with the museum’s interior and exhibits, it just wouldn’t be the same without them.

The museum does far more than tell the story of the terrible massacre that happened here. It is a historical society that looks at all aspects of the area’s history including a small exhibit about baseball legend Cy Young. Born and raised on a farm near Gilmore, about eleven miles south of Gnadenhutten, his name in full was Denton True Young. In adulthood he was 6’2” and extremely strong as all manual farm workers in that era were wont to be. The museum’s information sign about him showed a photo of the family barn and reported he hung a horse collar over the doorway that he used to practice throwing baseballs through.

He started his baseball career playing with local teams. In 1890 he tried out for the Tri-State League in Canton, Ohio. So shy was he that it took him six attempts before he mustered enough courage to enter the ballpark. The manager of Canton’s team, George Moreland, signed Young up for a monthly salary of $40. His fastballs pounded the grandstand boards, prompting a catcher to give him the nickname “Cyclone.” A sportswriter shortened it to “Cy.” Halfway through the season the Tri-state League collapsed, so Young joined the National League team Cleveland Spiders in August for $300 a year.

Cy played with them until 1898 when the team’s owner, Frank Robison, bought the Cardinals and decided to send his best players to St. Louis, Young among them. That year he made an impressive $2,400. Three years later he departed and joined the Boston Pilgrims, one of the teams belonging to the newly formed American League. The Pilgrims soon changed their name to the Red Sox.

In 1903 Young pitched his first World Series. In 1909 he moved to the Cleveland Indians and in 1911 spent the season’s second half with the Boston Braves. He retired in 1912 and moved to Peoli, about twelve miles south of Gnadenhutten. He lived to be eighty-eight and at the age of eighty-six threw the ceremonial pitch at the 1953 World Series between the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Yankees. Yogi Berra caught the ball.

The museum’s interior is filled with life size manikins, mostly Native Americans, that were clearly handmade. This sort of thing is fine when done well, but I’ve found that most museums, especially small ones, rarely have ones that ought to be seen by the public. Most of this museum’s manikins are creepy and amateurish, one notable exception being the excellent one of John Heckewelder—who reformed the town after its destruction—in the backroom. Despite their shortcomings, the manikins are so well integrated with the museum’s interior and exhibits, it just wouldn’t be the same without them.

John Heckewelder

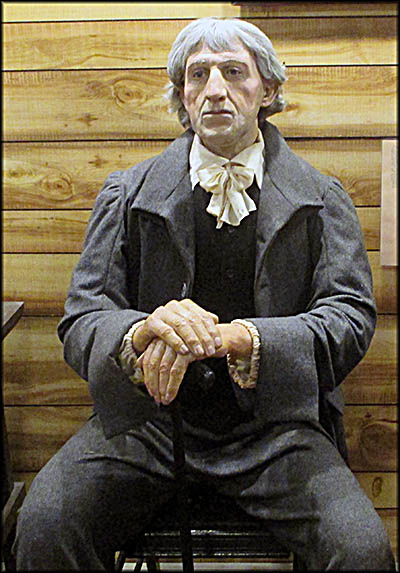

Medicine Case

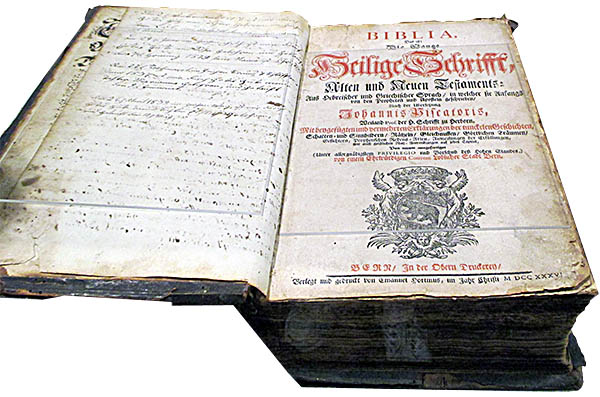

Bible Written in German

The museum has on display a book containing a list of vagrant animals. The person who found one would be given it if it wasn’t reclaimed after a listed deadline. Complementing this is the ear mark book that contained a print of different animals in the community used like a fingerprint that could be used to prove if a person had stolen an animal. Other books include McGuffey Readers and David Zeisberger’s 1776 book Essay of a Delaware-Indian and English Spelling-Book, for the Use of the Schools of the Christian Indians on Muskingum River. So important was he to the community that they preserved the branch from an apple tree that he planted in 1772 that was knocked over by the wind on July 16, 1889, with three bushels of apples on it. Another item with sentimental value is a cane made from the floorboards of the village’s church dedicated in 1802. Many community Bibles, some quite old and most in German, are here as well, including one printed in 1748 that David Zeisberger gave to fifteen-year-old Elizabeth Blickensderfer, who was living in his home at the time.🕜

Gnadenhutten Museum and Historic Site

Museum Interior