Garfield Heights Historical Museum

Museum

Loom

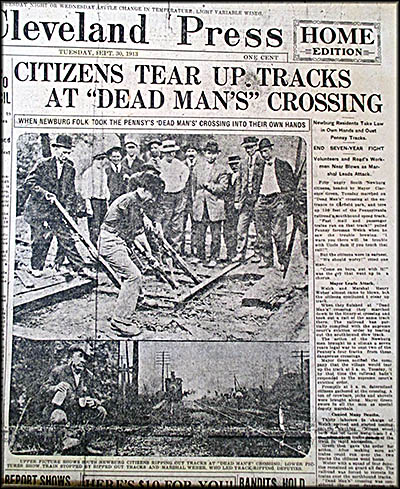

This newspaper clipping is hanging on a wall.

China Cabinet

Ham Radio Set

Authors of popular history tend to write about the sexier parts of the past such as wars, mass social movements, and pandemics. This is in part because we want readers to engage with history and there’s nothing better to make things interesting than some drama. I’ve always been interested in how the average person lived, and Garfield Heights is the perfect candidate for this kind of history. A Cleveland suburb, Garfield Heights served primarily as a residential city for those who didn’t want to live in the lower parts of Cleveland that tended to be swampy. Suburbs keen to attract those who wanted to move to a healthier environment put the word “Heights” in their name to advertise they were a better place to live in then, say, Cleveland’s Flats.

The building that now serves as the headquarters for the Garfield Heights Historical Society (GHHS) was built by the St. John Evangelical Church in 1890 to serve as the home for the principals of its school. The last moved out in 1953. Two years later the church sold the property to Joseph Ellis, but not the land. The house was moved from Granger Road to its present location on Turney Avenue. When Ellis moved into a nursing home in 1992, the Garfield Heights bought his house to serve as the headquarters of the GHHS.

The building that now serves as the headquarters for the Garfield Heights Historical Society (GHHS) was built by the St. John Evangelical Church in 1890 to serve as the home for the principals of its school. The last moved out in 1953. Two years later the church sold the property to Joseph Ellis, but not the land. The house was moved from Granger Road to its present location on Turney Avenue. When Ellis moved into a nursing home in 1992, the Garfield Heights bought his house to serve as the headquarters of the GHHS.

Garfield Heights traces its origins back to Newburgh Township, one of the first two settlements in the Western Reserve. The township, which disappeared because Cleveland gobbled most of it up, was initially settled by Germans and some Czechs. The construction of the Ohio and Erie Canal brought in a number of New Englanders and Irish, and the building of the railroad in 1855 attracted more Irish as well as Welsh and Bohemians. Poles started arriving at the turn of the twentieth century.

One part of the township that Cleveland didn’t annex was the hamlet of Newburgh in which Abram Garfield, father of President James Garfield, settled in 1820. Here James’ older brother, Thomas, helped to found the Miles Avenue Church of Christ, which still exists. Its second minister was James, who, despite not being ordained, served as its pastor from 1859 to 1860.

Newburgh’s citizens voted to upgrade their hamlet to the far more prestigious status of village in 1899. In 1904 Newburgh merged with Independence to the south as well as part of the Valley View area to become South Newburgh (not “Newburg” as some sources have erroneously spelled it). At this time Clevelanders tired of living in cramped thirty-five feet wide lots began moving onto the forty feet wide ones carved out here from farmland. The generous extra five feet of land per lot was reduced eliminated in the Warner Road area, but this made no difference. Access to a streetcar that took residents into Cleveland made it attractive to live in.

In 1895 Cleveland donated the land for and created Newburgh Park, which was renamed Garfield Heights Park in 1901. Filled with beautiful rolling hills complete with the flora and fauna found in rural areas, it was the perfect place for Clevelanders to go for some fresh country air. Its two ponds served as a place for rowing in the summer and ice skating in the winter, at least until pollution from Maple Heights ruined them. Though the ponds are long gone, the park is not. Owned and administered by Cleveland Metroparks, it is now called the Garfield Park Reservation.

One part of the township that Cleveland didn’t annex was the hamlet of Newburgh in which Abram Garfield, father of President James Garfield, settled in 1820. Here James’ older brother, Thomas, helped to found the Miles Avenue Church of Christ, which still exists. Its second minister was James, who, despite not being ordained, served as its pastor from 1859 to 1860.

Newburgh’s citizens voted to upgrade their hamlet to the far more prestigious status of village in 1899. In 1904 Newburgh merged with Independence to the south as well as part of the Valley View area to become South Newburgh (not “Newburg” as some sources have erroneously spelled it). At this time Clevelanders tired of living in cramped thirty-five feet wide lots began moving onto the forty feet wide ones carved out here from farmland. The generous extra five feet of land per lot was reduced eliminated in the Warner Road area, but this made no difference. Access to a streetcar that took residents into Cleveland made it attractive to live in.

In 1895 Cleveland donated the land for and created Newburgh Park, which was renamed Garfield Heights Park in 1901. Filled with beautiful rolling hills complete with the flora and fauna found in rural areas, it was the perfect place for Clevelanders to go for some fresh country air. Its two ponds served as a place for rowing in the summer and ice skating in the winter, at least until pollution from Maple Heights ruined them. Though the ponds are long gone, the park is not. Owned and administered by Cleveland Metroparks, it is now called the Garfield Park Reservation.

Along one of Garfield Park’s borders, Broadway Avenue, there was a notorious pair of rail tracks known as “Dead Man’s Crossing,” named as such because a number of people and vehicles were hit and killed by fast moving Pennsylvania Railroad trains here. South Newburgh wanted the tracks removed and, to that end, started seven years of litigation. In 1910 a court ruled in favor of South Newburgh. Plans were developed to build an overpass but a dispute over its position bogged it down. In 1912 the Ohio Supreme Court ruled the Pennsylvania Railroad had illegally put its tracks in South Newburgh.

After more procrastination, the village gave the Pennsylvania Railroad until 5 a.m. on September 30, 1913, to remove the tracks. On the night of the September 29, a Pennsylvania Railroad crew finally began the process but only removed one set of the tracks. The next evening Mayor Clarence N. Green warned the Pennsylvania Railroad that if it didn’t have the other tracks out by five the next morning, the village would do it. The next morning the tracks were still there so the mayor, accompanied by several councilmen and the village marshal, Henry Weber, led villagers to the spot and at six started work. Shortly after a Pennsylvania Railroad crew supervised by Daniel J. Welsh arrived to begin this very work. He told Mayor Green his men planned to start that afternoon, but the villagers didn’t relent. By 7:30 the tracks were gone.

In 1917, South Newburgh had a population of around 1,500 with no police or fire departments. Sewer, sidewalks and streetlights didn’t exist. Even the U.S. Post Office didn’t deliver here. Residents had to take a twenty mile round trip to Bedford to pick up their mail, which neighbors often took turns getting for everyone. No stores existed. Garfield Boulevard was unpaved, although streetcars did arrive every half hour. Few residents had telephones. The village did have a one-room schoolhouse called Park Knoll. Unsatisfied with the village’s name, its residents changed it to Garfield Heights in 1919, supposedly because James Garfield routinely walked through the village to get to Hiram College.

After more procrastination, the village gave the Pennsylvania Railroad until 5 a.m. on September 30, 1913, to remove the tracks. On the night of the September 29, a Pennsylvania Railroad crew finally began the process but only removed one set of the tracks. The next evening Mayor Clarence N. Green warned the Pennsylvania Railroad that if it didn’t have the other tracks out by five the next morning, the village would do it. The next morning the tracks were still there so the mayor, accompanied by several councilmen and the village marshal, Henry Weber, led villagers to the spot and at six started work. Shortly after a Pennsylvania Railroad crew supervised by Daniel J. Welsh arrived to begin this very work. He told Mayor Green his men planned to start that afternoon, but the villagers didn’t relent. By 7:30 the tracks were gone.

In 1917, South Newburgh had a population of around 1,500 with no police or fire departments. Sewer, sidewalks and streetlights didn’t exist. Even the U.S. Post Office didn’t deliver here. Residents had to take a twenty mile round trip to Bedford to pick up their mail, which neighbors often took turns getting for everyone. No stores existed. Garfield Boulevard was unpaved, although streetcars did arrive every half hour. Few residents had telephones. The village did have a one-room schoolhouse called Park Knoll. Unsatisfied with the village’s name, its residents changed it to Garfield Heights in 1919, supposedly because James Garfield routinely walked through the village to get to Hiram College.

One would hardly have guessed that from these humble beginnings this village would one day develop into a bustling city. Between 1920 and 1930 its population grew by a staggering 511 percent. One person who watched this firsthand was Joseph A. Schmitt. Born on August 17, 1888, on a farm along Turney Road, now one of Garfield Height’s main thoroughfares, it was his grandfather who had made the bricks for the aforementioned Park Knoll School. In his free time, Schmitt often grabbed a ride into Cleveland proper with his father, who went there daily to deliver milk in what is now Cleveland’s Slavic Village. While in the city, young Schmitt was exposed to its many cultural offerings.

Schmitt attended the Dyke School of Commerce in Cleveland. He tried and failed to start a bus line, opened a branch of the Dime Savings and Loan Bank, then moved into real estate. In addition to his business work, he was appointed South Newburgh’s justice of the peace, an office of law enforcement that no longer exists in Ohio. He was responsible for local civil and minor criminal matters. When World War I broke out, this position exempted him from the draft. Schmitt’s younger brother, Mathias, served in France where he died in Battle of Meuse-Argonne, which began on September 26, 1918, and didn’t conclude until the Armistice on November 11.

Schmitt attended the Dyke School of Commerce in Cleveland. He tried and failed to start a bus line, opened a branch of the Dime Savings and Loan Bank, then moved into real estate. In addition to his business work, he was appointed South Newburgh’s justice of the peace, an office of law enforcement that no longer exists in Ohio. He was responsible for local civil and minor criminal matters. When World War I broke out, this position exempted him from the draft. Schmitt’s younger brother, Mathias, served in France where he died in Battle of Meuse-Argonne, which began on September 26, 1918, and didn’t conclude until the Armistice on November 11.

Schmitt’s real estate career ended with the arrival of the Great Depression. During that terrible time he found work at the New Deal’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, whose goal was to help people refinance their homes. When that program shut down, he joined the Federal Housing Association. At the age of seventy, Garfield Height’s mayor appointed him as Chairman of the Zoning and Planning Commission for the City. By this time Garfield Heights had a population of around 35,000.

The GHHS has preserved all sorts of interesting artifacts from Garfield Heights’ past. Our guide demonstrated for us one of the museum’s three phonographs. Sound was generated within a box. To make it louder one opened the two doors on its frontside. A wind-up phonograph made by the Edison Company played wax cylinders.

The man who occupied the house in which the museum now resides, Joseph Ellis, was a keen ham radio operator and he left his set behind. I know virtually nothing about transmitting radios, but even I could tell this one was built long ago because it used vacuum tubes. Ham radios, for which you need a license to operate, can only communicate with other hams. Learning Morse Code was once a requirement to acquire an operator’s license, though now it isn’t. Ham radios allow people from across to world to speak to one another, the lingua franca being English.

Using shortwaves, ham operators communicate such long distances by bouncing radio waves off the ionosphere and even the moon. A more practical system of orbiting satellites carrying amateur radio (OSCAR) has made these techniques largely obsolete. Even in the age of the internet, the number of licensed ham operators is about 2.6 million worldwide. Next time there is a major natural disaster that knocks out traditional communications, if you check the news closely, you’re bound to find a story about how local ham operators kept the affected area in communication with the outside world.

The GHHS has preserved all sorts of interesting artifacts from Garfield Heights’ past. Our guide demonstrated for us one of the museum’s three phonographs. Sound was generated within a box. To make it louder one opened the two doors on its frontside. A wind-up phonograph made by the Edison Company played wax cylinders.

The man who occupied the house in which the museum now resides, Joseph Ellis, was a keen ham radio operator and he left his set behind. I know virtually nothing about transmitting radios, but even I could tell this one was built long ago because it used vacuum tubes. Ham radios, for which you need a license to operate, can only communicate with other hams. Learning Morse Code was once a requirement to acquire an operator’s license, though now it isn’t. Ham radios allow people from across to world to speak to one another, the lingua franca being English.

Using shortwaves, ham operators communicate such long distances by bouncing radio waves off the ionosphere and even the moon. A more practical system of orbiting satellites carrying amateur radio (OSCAR) has made these techniques largely obsolete. Even in the age of the internet, the number of licensed ham operators is about 2.6 million worldwide. Next time there is a major natural disaster that knocks out traditional communications, if you check the news closely, you’re bound to find a story about how local ham operators kept the affected area in communication with the outside world.

It is a rare historical society that doesn’t have at least one organ or piano, and this one is no exception. Its organ was powered by pumping foot pedals and was sold by S. Brainard’s Sons, a Cleveland firm founded in 1836 by Silas Brainard, a noted flautist. The company also sold musical instruments and published sheet music, songbooks, and the monthly journal Brainard’s Music World aimed at giving tips to aspiring musicians and writers of sheet music. The company moved to Chicago in 1889. One of Silas’ sons, Henry, remained in Cleveland to run a store that sold Steinway pianos.

The beautiful organ possessed by the GHHS was purchased around 1880 by Mrs. Maria Blase Bohning when she recognized that one of her ten children, ten-year-old Friedrich (Fred), had a talent for making music and asked for an instrument to play. Fred played it for many years until he followed an older brother out to California. Save for the occasional gathering or funeral, it lay fallow for many years until some of Mrs. Bohning’s grandchildren began using it. When the last Bohning to occupy the house died, most of its contents were either given to family or sold off. No one wanted the organ nor could a buyer be found. Imagine the surprise of one of Mrs. Bohning’s granddaughters when delivery men showed up at her house with it one day. Cousins had decided to bequeath it to her.🕜

The beautiful organ possessed by the GHHS was purchased around 1880 by Mrs. Maria Blase Bohning when she recognized that one of her ten children, ten-year-old Friedrich (Fred), had a talent for making music and asked for an instrument to play. Fred played it for many years until he followed an older brother out to California. Save for the occasional gathering or funeral, it lay fallow for many years until some of Mrs. Bohning’s grandchildren began using it. When the last Bohning to occupy the house died, most of its contents were either given to family or sold off. No one wanted the organ nor could a buyer be found. Imagine the surprise of one of Mrs. Bohning’s granddaughters when delivery men showed up at her house with it one day. Cousins had decided to bequeath it to her.🕜

Bohning Family Organ

Spinning Wheel

Living Room

Kitchen

President Garfield in Stained Glass