Charles Town Landing

Entrance

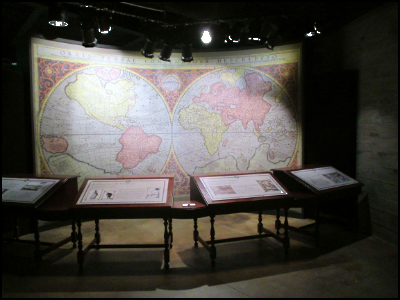

Inside the Museum

Here is an example of what representations of people in an historical scene should look like.

A statue of Cassique, chief of the Kiowa, stands proudly along the outdoor path.

Memory is an unreliable thing. I was certain I had last been at Charles Towne Landing in 1993, one year after Hurricane Hugo hit. But some fact checking before writing this travel log showed me I was wrong. It turned out this Category 4 storm had ripped into and devastated the Charleston area on September 22, 1989, not in 1992 as I had believed. I am therefore pretty sure I visited in early Spring 1991. Despite a nearly two year gap between when the hurricane hit and my original trip, Hugo’s footprint could still be seen in the form of a large number of downed and broken trees.

It had also leveled the Charles Towne Landing site, forcing its staff to rebuild it from ground up. But don’t worry: no historical buildings from the 1670s were damaged or lost because there were none. In fact, as of this writing, archeologists are still looking for signs of the original town for which they’ve only found one building. (Here I suggest they are looking in entirely the wrong place, similar to why it took archeologists so long to find the original Jamestown fort site. After the hurricane, the museum built a little town of “replica” buildings based not on what they knew was there but what they thought probably existed. It was set up something like Williamsburg, with historical reenactors scattered about. And here I thought faulty memory had gotten me again. I didn’t see said structures, causing me to wonder if I had this place confused with somewhere else. I asked someone at the Visitor’s Center and this fellow eased my mind. The replica town I remember did exist, but it is no more. He even showed me a map of what the site looked like when I first saw it. It had the buildings I remembered and nothing more. Since then the replica town has been taken down. These days you enter through the fairly new Visitor’s Center that includes a gift shop and an excellent museum.

It had also leveled the Charles Towne Landing site, forcing its staff to rebuild it from ground up. But don’t worry: no historical buildings from the 1670s were damaged or lost because there were none. In fact, as of this writing, archeologists are still looking for signs of the original town for which they’ve only found one building. (Here I suggest they are looking in entirely the wrong place, similar to why it took archeologists so long to find the original Jamestown fort site. After the hurricane, the museum built a little town of “replica” buildings based not on what they knew was there but what they thought probably existed. It was set up something like Williamsburg, with historical reenactors scattered about. And here I thought faulty memory had gotten me again. I didn’t see said structures, causing me to wonder if I had this place confused with somewhere else. I asked someone at the Visitor’s Center and this fellow eased my mind. The replica town I remember did exist, but it is no more. He even showed me a map of what the site looked like when I first saw it. It had the buildings I remembered and nothing more. Since then the replica town has been taken down. These days you enter through the fairly new Visitor’s Center that includes a gift shop and an excellent museum.

Starting a colony in North America required two things: getting the king’s permission and finding volunteers. The former was by far the easier to achieve. To entice the latter to come, the Lords Proprietors offered those who settled on the new Carolina colony something they were unlikely to ever get in Britain: land, and a lot of it. According to one of the museum’s information signs, a person who agreed to settle would receive 150 acres of land plus “150 more for every able Servant.” For every servant under the age of sixteen, he received 100 more acres. And servants, presumably of the indentured type, also received 100 acres of land when their contract was up.

According to a rather impressive-looking outdoor sign complete with raised letters, Charles Towne was “the first permanent English settlement in what is now S.C. [that] was established here in 1670” at Albemarle Point. Permanent it was not. A mere ten years later, the entire town moved across the Ashley River to the present site of downtown Charleston. The abandoned settlement, by 1700 known as “Old Town Plantation,” served as farmland for the next 300 years.

Charles Towne was a business venture masterminded by Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper, Baron of Shaftesbury, the man whose middle and last names were given to the two rivers between which the current downtown area of Charleston is located. As part owner of a very profitable sugar planation on Barbados, Ashley Cooper wished to expand elsewhere, and to that end convinced seven others to finance the venture. Collectively these men became known as the Lords Proprietors. Their plan was simple: establish a colony in what would on day be South Carolina and there grow a cash crop that would make them even richer than they already were.

Charles Towne was a business venture masterminded by Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper, Baron of Shaftesbury, the man whose middle and last names were given to the two rivers between which the current downtown area of Charleston is located. As part owner of a very profitable sugar planation on Barbados, Ashley Cooper wished to expand elsewhere, and to that end convinced seven others to finance the venture. Collectively these men became known as the Lords Proprietors. Their plan was simple: establish a colony in what would on day be South Carolina and there grow a cash crop that would make them even richer than they already were.

The trouble with giving so much land away was it belonged to someone else: the Native Americans. Imagine for a moment that a spaceship arrives in your city, 150 aliens disembark, then claim your house and land as their own. If you protest that it already belongs to you, they’ll use force to remove you. It’s also too bad that you have no immunity to the diseases the aliens brought with them, because chances are one of those will kill you. If not, the aliens can always sell you into slavery, which has the dual benefits of generating a profit and ridding the area of one of its troublesome humans.

It was just such a scenario that faced the native people in the Carolina region when the English colonists arrived. These settlers were neither ready or able to create a brand new town carved out of the wilderness, nor did they do very well feeding themselves. Fortunately for them, the Kiawah and other friendly Native American people helped them survive. Indeed, the Kiawah chief, known as the Cassique, offered to allow them to settle at Albemarle Point in exchange for help against their enemy, the Westos, who were armed with European guns. To this the settlers agreed. One of the museum’s information signs takes the Native Americans to task for giving the settlers aid, saying, “But in the end, their engagement with Charles Towne led to their own destruction.” This is unfair. Had they prevented the English from gaining a foothold in their territory, more would have come. And kept on coming in overwhelming numbers the Native Americans had no hope of stopping.

As if the incredible wrong committed against the Native Americans were not enough, the Lords Proprietors also gave the colonists the right to bring and own slaves of African origin into the colony because such a labor force worked so well in the English West Indies on the sugar plantations. Indeed, before the three ships bringing the colonists to Carolina—Port Royal, Albemarle, and Carolina—headed to their final destination, they stopped in Bridgetown, Barbados, to see how sugar plantations were run. To grow as much as possible, the island’s trees had been completely stripped away. The elite who owned the plantations ran the island with an iron first. Many free whites not of the planter class were treated not much better than the black slaves, who were brutalized.

It was just such a scenario that faced the native people in the Carolina region when the English colonists arrived. These settlers were neither ready or able to create a brand new town carved out of the wilderness, nor did they do very well feeding themselves. Fortunately for them, the Kiawah and other friendly Native American people helped them survive. Indeed, the Kiawah chief, known as the Cassique, offered to allow them to settle at Albemarle Point in exchange for help against their enemy, the Westos, who were armed with European guns. To this the settlers agreed. One of the museum’s information signs takes the Native Americans to task for giving the settlers aid, saying, “But in the end, their engagement with Charles Towne led to their own destruction.” This is unfair. Had they prevented the English from gaining a foothold in their territory, more would have come. And kept on coming in overwhelming numbers the Native Americans had no hope of stopping.

As if the incredible wrong committed against the Native Americans were not enough, the Lords Proprietors also gave the colonists the right to bring and own slaves of African origin into the colony because such a labor force worked so well in the English West Indies on the sugar plantations. Indeed, before the three ships bringing the colonists to Carolina—Port Royal, Albemarle, and Carolina—headed to their final destination, they stopped in Bridgetown, Barbados, to see how sugar plantations were run. To grow as much as possible, the island’s trees had been completely stripped away. The elite who owned the plantations ran the island with an iron first. Many free whites not of the planter class were treated not much better than the black slaves, who were brutalized.

The Carolina colonists were also allowed to bring indentured servants, which they did. This has caused some to argue that whites, too, were victims of slavery in America, but the comparison is wrong. Those who became indentured servants did so voluntarily with the promise that when they paid off the cost of their voyage to Carolina, they would be freed. Slaves of African dissent were kidnapped, treated as chattel rather than fellow human beings, and in most cases could never gain their freedom short of running away. Not that indentured servants were treated well. Some who found life in the colony too harsh fled to St. Augustine, which was controlled by the Spanish. Escaped slaves of African decent were welcomed by the Spanish in Florida.

Nearly all the information presented so far came the Visitor Center’s museum, and this is just a barebones account of the massive amount of information found on its walls. Once outside, the number of information signs diminishes considerably, as does interesting things to see. The first place one of my traveling companions and I encountered was an Native American archeological site predating the Charles Towne landing that was, according to those who dug it up, ceremonial in nature. However, archeologists ascribe religious connotations to just about everything they unearth, so I am a bit skeptical that they know its real purpose with certainty.

Archeologists have also been digging up the Horry-Lucas family’s plantation that once occupied these grounds, its mansion having burned down in 1865 during the Civil War. The overseer’s home, known as the Legare-Waring House, did survive and still stands on the site despite being as out of place as would a McDonalds in an 1870s recreation of Dodge City. Best I can tell, the museum offers no tours of the house, instead renting it out for parties and gatherings.

One of the few replica buildings visitors can enter is called the common house. Here African slaves and indentured servants slept. Inside there are no information signs to give context to what a person is seeing. Their addition would be welcome, although I would suggest a staff member or two dressed in period costume residing here to answer questions and tell visitors what life was like for who those who inhabited this dwelling would be even better.

Nearly all the information presented so far came the Visitor Center’s museum, and this is just a barebones account of the massive amount of information found on its walls. Once outside, the number of information signs diminishes considerably, as does interesting things to see. The first place one of my traveling companions and I encountered was an Native American archeological site predating the Charles Towne landing that was, according to those who dug it up, ceremonial in nature. However, archeologists ascribe religious connotations to just about everything they unearth, so I am a bit skeptical that they know its real purpose with certainty.

Archeologists have also been digging up the Horry-Lucas family’s plantation that once occupied these grounds, its mansion having burned down in 1865 during the Civil War. The overseer’s home, known as the Legare-Waring House, did survive and still stands on the site despite being as out of place as would a McDonalds in an 1870s recreation of Dodge City. Best I can tell, the museum offers no tours of the house, instead renting it out for parties and gatherings.

One of the few replica buildings visitors can enter is called the common house. Here African slaves and indentured servants slept. Inside there are no information signs to give context to what a person is seeing. Their addition would be welcome, although I would suggest a staff member or two dressed in period costume residing here to answer questions and tell visitors what life was like for who those who inhabited this dwelling would be even better.

The one thing I really wanted to see was the ship Adventure—technically a ketch—because I love going on tall ships. I had a devil time locating her because the full color map given to me at the Visitor’s Center is upside down. Whoever drew it thought it a good idea to orient it to the north despite the fact the grounds are south of the museum’s entry point. Once I figured this out, I rotated the map 180 degrees and was able to follow it with no problem.

On board the Adventure stood a staff member dressed in period costume who knew his stuff and told me all sorts of interesting things. The ketch was used as a trading vessel meant to go up and down the Atlantic Coast as well as to Barbados. The Lords Proprietors only goal was, after all, for the colony to make money and give them a return on their investment, so naturally they wanted the colonists to trade locally as well as find a cash crop to send back to England. The cash crop proved elusive. The tropical plants the colonists brought with them failed when the winter cold killed them. Other crops the colonists tried were indigo, cotton, ginger root, grapes and olives. Timber, of which Barbados had none and Britain little, served as the first cash crop. Trade with the native people in furs sold to Europe was also profitable. Although no information sign that I saw reported it, rice would one day become the area’s first renewable cash crop until one day being usurped by cotton.

The colonists chose to settle where they did in part out of the real fear that the Spanish to the south would attack them. No doubt they were aware that in 1565 the Spaniards had wiped out the French colony of Fort Caroline in Florida. As it turned out, the Spanish did make an attempt to attack Charles Towne, but a storm kept their ships from arriving. Out of concern for security and a desire for access to a deep water harbor, in 1680 the colonists moved across the Ashley River to Oyster Point, now Downtown Charleston, where they stayed free of the Spanish but did once have a nasty visit from the pirate Blackbeard.🕜

On board the Adventure stood a staff member dressed in period costume who knew his stuff and told me all sorts of interesting things. The ketch was used as a trading vessel meant to go up and down the Atlantic Coast as well as to Barbados. The Lords Proprietors only goal was, after all, for the colony to make money and give them a return on their investment, so naturally they wanted the colonists to trade locally as well as find a cash crop to send back to England. The cash crop proved elusive. The tropical plants the colonists brought with them failed when the winter cold killed them. Other crops the colonists tried were indigo, cotton, ginger root, grapes and olives. Timber, of which Barbados had none and Britain little, served as the first cash crop. Trade with the native people in furs sold to Europe was also profitable. Although no information sign that I saw reported it, rice would one day become the area’s first renewable cash crop until one day being usurped by cotton.

The colonists chose to settle where they did in part out of the real fear that the Spanish to the south would attack them. No doubt they were aware that in 1565 the Spaniards had wiped out the French colony of Fort Caroline in Florida. As it turned out, the Spanish did make an attempt to attack Charles Towne, but a storm kept their ships from arriving. Out of concern for security and a desire for access to a deep water harbor, in 1680 the colonists moved across the Ashley River to Oyster Point, now Downtown Charleston, where they stayed free of the Spanish but did once have a nasty visit from the pirate Blackbeard.🕜

One form of punishment at Charles Towne was placement in the stocks, an extremely unpleasant, backbreaking form of torture.

Cannons

This is a common house where African slaves and indentured servants lived.

The Legare-Waring House is out of place on what is supposed to be a representation of the original Charles Towne landing site. It is like putting a McDonalds in a street scene of 1870s Dodge City.

Ashley River

Ship Under Construction