Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum

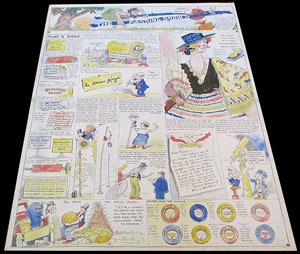

You will see Billy Ireland’s current events pages “The Passing Show” in the lobby.

You will reach the museum by passing through these doors.

After entering the lobby, climb upstairs and use this door to enter the museum proper.

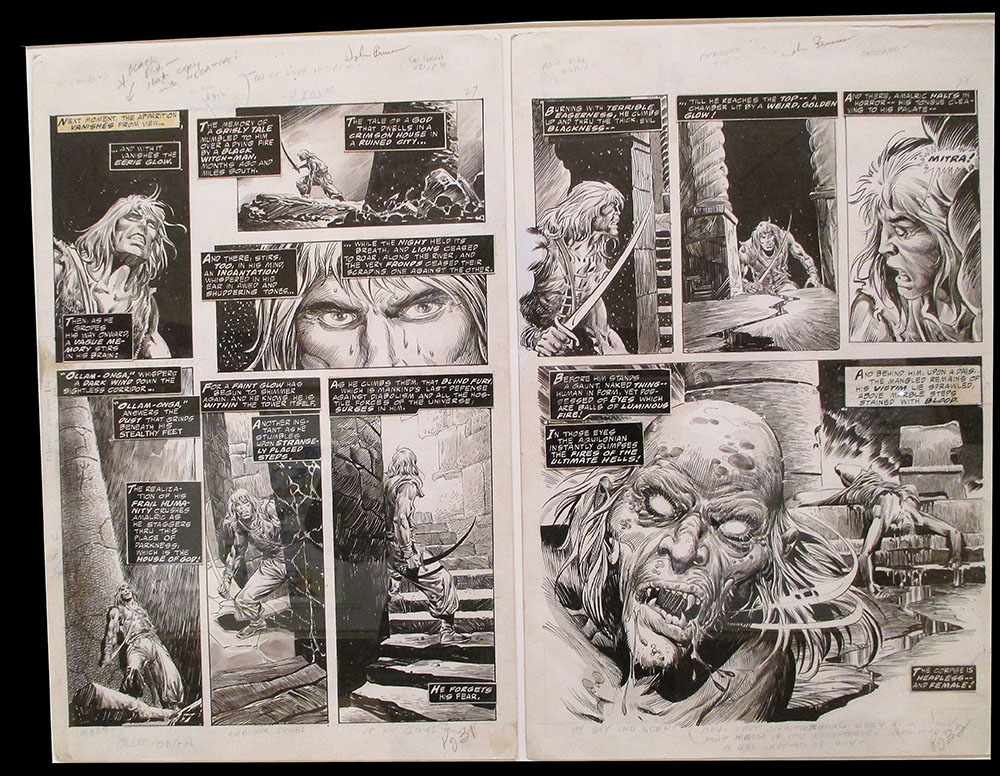

This original piece from Marvel Comics The Savage Sword of Conan the Barbarian (August 1977, #21) by John Buscema shows the margin notes and other irregularities that never appeared in the final printed page.

In my youth I wanted, more than anything else, to one day become a cartoonist. Alas, desire and passion fail to make a good substitute for ability and talent, and, lacking both, this dream never panned out. Instead of cartooning, I went to college to study my second love, history, and now my two passions have come together in one place: the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. Despite my extensive knowledge of comic book artists and writers, I must admit I’d never heard of him. This, it turns out, is because his work appeared in the Columbus Dispatch, a newspaper with which I’m unfamiliar. Born in Chillicothe, Ohio, on January 8, 1880, Ireland, according to the plaque about him, “drew editorial cartoon and spot illustrations” as well as a current events page called “The Passing Show.” He worked for the paper from the late 1890s “until his death in 1935.” Neither the plaque nor museum website specifically state why the museum took Ireland’s name as its own, although I would imagine it has to do with his local fame and possibly his support of Ohio State University.

The building in which you will find the museum, Sullivant Hall, stands on a city thoroughfare, High Street, so you don’t have to worry about getting onto the Ohio State campus proper and navigating its roads. Although you will find the Ohio Union Garage—South just three buildings away at 1759 North High Street, on weekdays you can’t park there without a permit until after 4:00 p.m. Because my traveling companions and I visited on a Saturday and during Ohio State’s Christmas vacation, this didn’t present us with a problem.

To get to the museum, visitors must use one of Sullivant Hall’s side entrances. Upon passing through its doors, they will see a large lobby with the Billy Ireland Library to the left and stairs ahead. Take these or the elevator up the second level to reach the museum itself. This, although not exceptionally large, has four rooms, three of which constitute the galleries. The museum has the quality and look of any top one in the nation, and enough art in its modest area to keep you occupied for a good hour and maybe two or three if you want to read every display. The day we visited visitors packed it, slowing our progress a bit. For those planning to go, I suggest you do so during one of Ohio State’s breaks so you can avoid the heavy pedestrian and auto traffic generated by the student body and faculty. Or, if you can only schedule a visit during a school session, try to avoid picking a day when a sporting event takes place.

To get to the museum, visitors must use one of Sullivant Hall’s side entrances. Upon passing through its doors, they will see a large lobby with the Billy Ireland Library to the left and stairs ahead. Take these or the elevator up the second level to reach the museum itself. This, although not exceptionally large, has four rooms, three of which constitute the galleries. The museum has the quality and look of any top one in the nation, and enough art in its modest area to keep you occupied for a good hour and maybe two or three if you want to read every display. The day we visited visitors packed it, slowing our progress a bit. For those planning to go, I suggest you do so during one of Ohio State’s breaks so you can avoid the heavy pedestrian and auto traffic generated by the student body and faculty. Or, if you can only schedule a visit during a school session, try to avoid picking a day when a sporting event takes place.

Although organized by topic rather than chronologically, the museum nonetheless covers the full scope of comic strip and book history. Most comics historians believe the first strip to ever use the word “cartoon” showed up in the July 15, 1843, issue of the British satirical periodical Punch as the caption for a John Leech drawing. The museum possesses both original art and rare printed materials. Take, for example, a piece by Windsor McCay called A Tale of the Jungle Imps. Published on June 28, 1903, comics historians believed no printed versions existed until 2006 when someone donated materials to museum that included five copies.

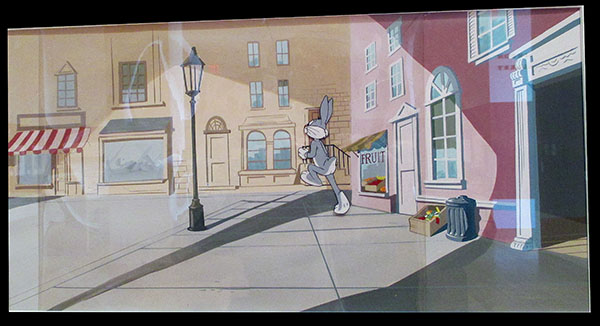

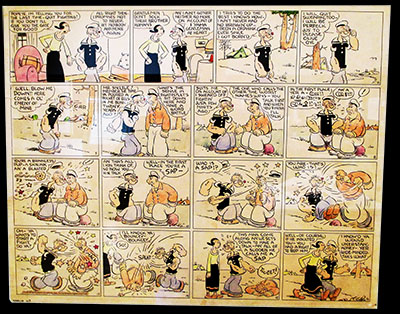

One will also find on display a print of the Sunday, March 27, 1932, strip of Elzie Segar’s Thimble Theater. Although at this point it starred Popeye the Sailor, that character didn’t appeared until 1929, ten years after it began. Most visitors will probably know Popeye better from the cartoons in which he appeared rather than Thimble Theater, and those interested in animation will want to take time to look at a cell from a Bugs Bunny cartoon (circa 1953).

One will also find on display a print of the Sunday, March 27, 1932, strip of Elzie Segar’s Thimble Theater. Although at this point it starred Popeye the Sailor, that character didn’t appeared until 1929, ten years after it began. Most visitors will probably know Popeye better from the cartoons in which he appeared rather than Thimble Theater, and those interested in animation will want to take time to look at a cell from a Bugs Bunny cartoon (circa 1953).

The museum has a vast array of comic book art as well. Among these treasures one will find items from Marvel and DC Comics. Being a Marvel man myself, I immediately gravitated towards those from that publisher. To my delight, I found on display original art from two of my favorite Marvel titles, The Incredible Hulk and The Savage Sword of Conan the Barbarian, the latter long ago cancelled, although Dark Horse continues to publish a variation of it. Marie Severin drew the page from The Incredible Hulk and John Buscema the one from The Savage Sword of Conan. I felt a chill of joy when I saw the latter because I own a printed copy and knew it on sight. I always admired Buscema’s work (although he doesn’t qualify as one of my favorite comic artists) and found viewing the original quite interesting. In it you can see whiteout and ink blemishes that just didn’t show up in the printed version, as well as some handwritten notes in the margins.

The museum displays some of the most important and influential comic strips to every appear in newspapers—including Peanuts, Garfield, B.C., Calvin and Hobbes, and Beatle Bailey—yet neither I nor my travelling companions saw a single print or original piece from Gary Larson’s now defunct newspaper strip The Far Side on display. Surely of all the newspaper strips that have run within the last thirty years, this has proved one of the most influential, an obvious observation considering the many (inferior) knock-offs still being published. And so I implore the museum curators to remedy this miscarriage of cartooning justice!🕜

The museum displays some of the most important and influential comic strips to every appear in newspapers—including Peanuts, Garfield, B.C., Calvin and Hobbes, and Beatle Bailey—yet neither I nor my travelling companions saw a single print or original piece from Gary Larson’s now defunct newspaper strip The Far Side on display. Surely of all the newspaper strips that have run within the last thirty years, this has proved one of the most influential, an obvious observation considering the many (inferior) knock-offs still being published. And so I implore the museum curators to remedy this miscarriage of cartooning justice!🕜

One of the display cases. Each drawer contains more art quite worth gazing at.

A cell from a Bug Bunny cartoon circa 1953.

The extremely popular Popeye the Sailor Man did not appear in Thimble Theater by E.C. Segar until its tenth year (March 27, 1932).

This rare piece of art by Winsor McCay, A Tale of Jungle Imps, appeared on June 28, 1903. Until 2006, no copies were thought to exist.