AuGlaize Village & Farm Museum

If you got your hands on a time machine and snatched someone who lived in Defiance County, Ohio, from the year 1840 and brought this individual to the present day, he or she wouldn’t recognize the place. In 1840, the county was covered with mud, stagnant water in wet seasons, and trees so large it defied belief. It was in the heart of the Great Black Swamp, which once covered much of Northwest Ohio. Today Defiance County and pretty much the rest of Northwest Ohio is devoid of trees. Being flat, you can see for miles in any direction and, with the exception of the odd city, town or village, nearly all of it is farmland.

The AuGlaize Village & Farm Museum takes a snapshot of Defiance County’s history from its post-Black Swamp era. This living history museum consists primarily of historic structures rescued from other parts of Defiance County. It was established in 1966 and originally consisted of forty acres donated by Charles Mansfield that included a red barn. The Defiance County Historical Society, which runs the museum, purchased an additional eighty acres in 1975. The village stands on just small portion of this land. A roughly one-mile-long railroad track surrounds the property and if you come on a day when it’s running, you can take a train ride.

The museum has no regular hours. Every year it hosts special events and at that time it’s open to the public. Those wishing to visit another time can, like I did, make an appointment. My traveling companion and I began at the Visitor’s Center, a small structure in which you pay a modest entry fee and can, if you wish, consult the museum’s library. There are posters, postcards, and a variety of other items on display to examine before moving into the village proper. Scott Lantow served as our guide. For nearly four hours he took us through most of the museum’s buildings, imparting his encyclopedic knowledge about them and their context within Defiance County’s history.

The AuGlaize Village & Farm Museum takes a snapshot of Defiance County’s history from its post-Black Swamp era. This living history museum consists primarily of historic structures rescued from other parts of Defiance County. It was established in 1966 and originally consisted of forty acres donated by Charles Mansfield that included a red barn. The Defiance County Historical Society, which runs the museum, purchased an additional eighty acres in 1975. The village stands on just small portion of this land. A roughly one-mile-long railroad track surrounds the property and if you come on a day when it’s running, you can take a train ride.

The museum has no regular hours. Every year it hosts special events and at that time it’s open to the public. Those wishing to visit another time can, like I did, make an appointment. My traveling companion and I began at the Visitor’s Center, a small structure in which you pay a modest entry fee and can, if you wish, consult the museum’s library. There are posters, postcards, and a variety of other items on display to examine before moving into the village proper. Scott Lantow served as our guide. For nearly four hours he took us through most of the museum’s buildings, imparting his encyclopedic knowledge about them and their context within Defiance County’s history.

Jewell Railroad Depot

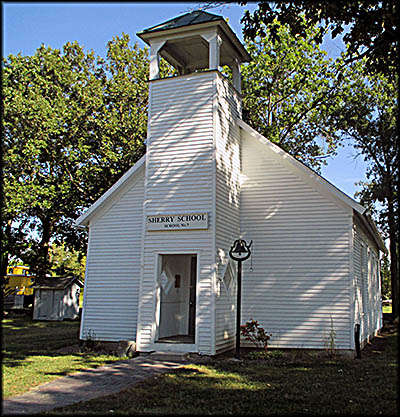

Our first stop after leaving the Visitor’s Center was the one-room Sherry Schoolhouse, which once stood about a mile south of its current location and served children from the first to eighth grade. While here, Lantow told us that the first schoolhouse in the county was in the city of Defiance in blacksmith’s shop of all places. Later, the purpose-built building that replaced it had oil-soaked paper for windows to keep the elements out. Considering that in its earliest days Defiance stood in the midst of a swamp, this no doubt included keeping mosquitoes out.

Beside the schoolhouse was an A-framed contraption that consisted of three wooden boxes all of the same weight wrapped by ropes connected to pulleys. The one on the right had one pulley, making lifting the box difficult. The one in the center had two pulleys, allowing you to lift it with less strength. The one on the left had four pulleys, making this the easiest to lift. The museum put this here to give visiting schoolchildren something to interact with.

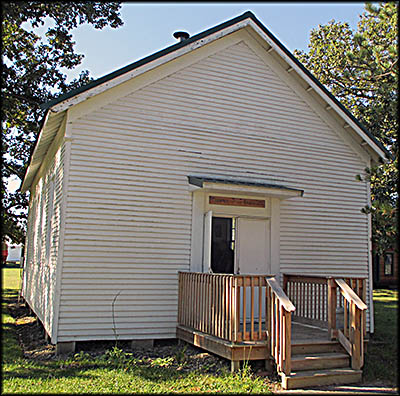

A congregation of German immigrants built the uninspired, boxy St. John Lutheran Church in 1875, and it served them until 1904 when a new church replaced it. At that point the old one was turned into a school. One of the three defunct organs currently in the church—the pump one in the best shape—was purchased by the congregation in 1892. We were told none of the museum’s volunteers or staff know how to play an organ, so restoring one isn’t something anyone is keen on doing at present.

Beside the schoolhouse was an A-framed contraption that consisted of three wooden boxes all of the same weight wrapped by ropes connected to pulleys. The one on the right had one pulley, making lifting the box difficult. The one in the center had two pulleys, allowing you to lift it with less strength. The one on the left had four pulleys, making this the easiest to lift. The museum put this here to give visiting schoolchildren something to interact with.

A congregation of German immigrants built the uninspired, boxy St. John Lutheran Church in 1875, and it served them until 1904 when a new church replaced it. At that point the old one was turned into a school. One of the three defunct organs currently in the church—the pump one in the best shape—was purchased by the congregation in 1892. We were told none of the museum’s volunteers or staff know how to play an organ, so restoring one isn’t something anyone is keen on doing at present.

Chesapeake & Ohio Caboose

Photo taken from the window of the caboose.

The Jewell Railroad “Station” should be designated as a depot. Among other differences, railroad stations were places where passenger trains always stopped, while at depots like this one, they only did so if the signal that passenger needed to be picked was displayed. The Jewell depot was built by the Toledo, Wabash & Western Railroad in 1856. This eventually became part of the Wabash Railroad, which later merged with Norfolk & Western. It was eliminated altogether when N&W became Norfolk Southern. N&W donated the depot to the Defiance Historical Society in 1962, and after its move to AuGlaize Village, the AuGlaize Village Railroad Club restored it.

That same organization also restored the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad caboose on the other side of the building. Built in 1929 as 90950, the Chessie System donated it to the museum in 1975. At some point the Boy Scouts painted the caboose red, but the AuGlaize Village Railroad Club repainted it yellow, the color the Chessie used. Near this is a small steam engine (probably only used in a railroad yard) that the AuGlaize Museum is going to give to a place in Indiana.

That same organization also restored the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad caboose on the other side of the building. Built in 1929 as 90950, the Chessie System donated it to the museum in 1975. At some point the Boy Scouts painted the caboose red, but the AuGlaize Village Railroad Club repainted it yellow, the color the Chessie used. Near this is a small steam engine (probably only used in a railroad yard) that the AuGlaize Museum is going to give to a place in Indiana.

Passenger Pigeon

The post office on the museum’s ground came from Mark Center, an unincorporated community said to have gained its name because it’s at the center in Mark Township. Mrs. Marietta Kyle successfully applied for the creation of a post office for this location in 1875 and, after doing so, became its postmistress. The building on the museum grounds isn’t large, but in addition to being a post office, it once housed a doctor’s office, a barber shop, and served as an office for a hay business.

Our guide connected Mark Center with an interesting historical event. William J. Knight and Wilson Brown both joined Ohio regiments as volunteers at the outbreak of the Civil War, and our guide told us Knight came from Mark Center. When I looked at Knight’s person history, I found he was born and raised in Wayne County, and after the war settled in the village of Stryker in Williams County. In any case, both he and Brown at some point lived in Northwest Ohio, and both had worked as railroad engineers before the outbreak of the war.

In 1862, a civilian spy working for the Union, James J. Andrews, came up with a daring plan to disrupt the Confederacy’s ability to move troops to the besieged city of Chattanooga, Tennessee. He and a detachment of Union soldiers would accomplish this by stealing a locomotive in Georgia. As it headed north, they’d destroy as much infrastructure as they could. In partnership with another civilian, William “Bill” Campell, Andrews gathered twenty-two Ohio volunteers to pull off the raid, a group that included Knight and Brown. The soldiers headed south dressed as civilians.

Our guide connected Mark Center with an interesting historical event. William J. Knight and Wilson Brown both joined Ohio regiments as volunteers at the outbreak of the Civil War, and our guide told us Knight came from Mark Center. When I looked at Knight’s person history, I found he was born and raised in Wayne County, and after the war settled in the village of Stryker in Williams County. In any case, both he and Brown at some point lived in Northwest Ohio, and both had worked as railroad engineers before the outbreak of the war.

In 1862, a civilian spy working for the Union, James J. Andrews, came up with a daring plan to disrupt the Confederacy’s ability to move troops to the besieged city of Chattanooga, Tennessee. He and a detachment of Union soldiers would accomplish this by stealing a locomotive in Georgia. As it headed north, they’d destroy as much infrastructure as they could. In partnership with another civilian, William “Bill” Campell, Andrews gathered twenty-two Ohio volunteers to pull off the raid, a group that included Knight and Brown. The soldiers headed south dressed as civilians.

Dried Tobacco

At Big Shanty, Georgia, the raiders stole the locomotive known as The General. Pulling a tender and three empty boxcars, it steamed north. Along the way the sabotage team destroyed telegraph lines and attempted to wreck the track. The Confederates pursued using three different locomotives, forcing the Union men to move at a pace that precluded them from taking on water and fuel. As a result, after seven hours and almost ninety miles of track, The General ran out of steam. All Union raiders were captured and many, included Andrews, were executed. Brown and Knight were sent to a POW camp from which both escaped. They were given some of the first Medals of Honor ever awarded.

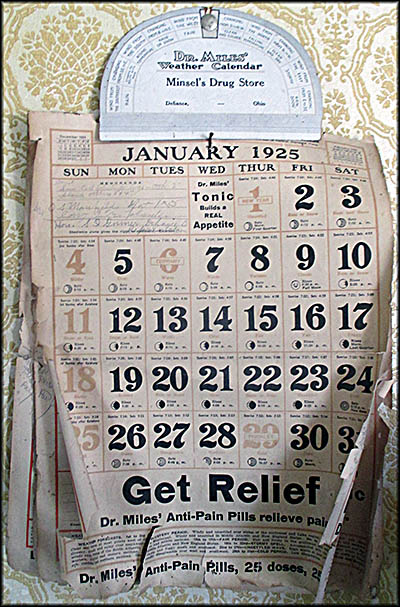

No living museum consisting of historic buildings would be complete without a doctor’s office, and AuGlaize Village has an excellent example of one. It’s the one used by Doctor Robert B. Cameron from 1874 to 1916 during his time practicing in Jewell. Born in Bryan, Ohio, Cameron studied medicine in Michigan. He started his first practice in the Defiance County village of Evansville in April 1873, then moved to Jewell the next year. After leaving that latter, he set up a new practice in the city of Defiance where he worked until retiring in 1935. He also served in the Ohio legislature between 1912 and 1918, and was the Defiance County Health Commissioner from 1920 to 1935.

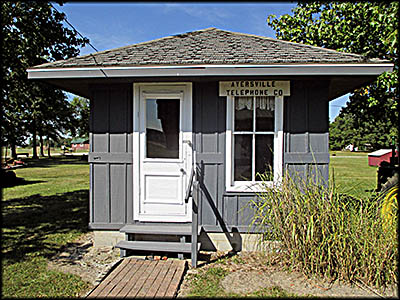

On October 14, 1904, farmers gathered in Ayersville, an unincorporated community, to plan the creation of a telephone system for their community. They founded the Ayersville Telephone Company, which one might consider a wildcat operation because it had no connection with any of the Bell companies that monopolized most of the U.S. telephone system until the breakup of AT&T in 1984.

No living museum consisting of historic buildings would be complete without a doctor’s office, and AuGlaize Village has an excellent example of one. It’s the one used by Doctor Robert B. Cameron from 1874 to 1916 during his time practicing in Jewell. Born in Bryan, Ohio, Cameron studied medicine in Michigan. He started his first practice in the Defiance County village of Evansville in April 1873, then moved to Jewell the next year. After leaving that latter, he set up a new practice in the city of Defiance where he worked until retiring in 1935. He also served in the Ohio legislature between 1912 and 1918, and was the Defiance County Health Commissioner from 1920 to 1935.

On October 14, 1904, farmers gathered in Ayersville, an unincorporated community, to plan the creation of a telephone system for their community. They founded the Ayersville Telephone Company, which one might consider a wildcat operation because it had no connection with any of the Bell companies that monopolized most of the U.S. telephone system until the breakup of AT&T in 1984.

Replica of the dentist's office used by Dr. Emery Blosser.

In December of that same year, several of these farmers headed into the forest and, says an information sign, “cut some native black ash to make telephone poles, 26 feet in lenght [sic] … Twenty men built lines on January 18 and 19. Seven lines were built from Tom Craig’s to the town of Stanley at this time. Total construction cost for 27 members was $519.75. Each subscriber bought his own telephone before the new system was put in. The cost of the telephone was $11.28.” The home of George Kneese served as the first telephone office. It was replaced by the building now on the museum’s grounds. The office stayed open during daylight hours. Operators rang off at 9 pm in the winter and 8:30 pm in the summer. The system relied on one, then two switchboards for connecting calls. Direct dialing began on October 16, 1966.

Two of the museum’s buildings once belonged to the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the New Deal program that improved and revived public land. During World War II, these particular CCC buildings were repurposed as mess halls for the German POWs being held in a camp on the south side of the Maumee River in the city of Defiance. It was the third largest camp in Ohio with about 800 men.

Locals grumbled that these POWs did nothing all day and received better food than what an American could get. What most locals didn’t realize was that the POWs—most of them young conscripts and none of them dedicated Nazis—were being bussed out daily to work on regional farms to help alleviate the farmhand shortage. At one place, a farmer asked if he could feed the POWs hot dogs for lunch. When told yes, this person did so, and afterwards, the grateful POWs worked twice as hard. When the Army’s Inspector General made what the POWs were doing public, the locals stopped grumbling.

Two of the museum’s buildings once belonged to the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the New Deal program that improved and revived public land. During World War II, these particular CCC buildings were repurposed as mess halls for the German POWs being held in a camp on the south side of the Maumee River in the city of Defiance. It was the third largest camp in Ohio with about 800 men.

Locals grumbled that these POWs did nothing all day and received better food than what an American could get. What most locals didn’t realize was that the POWs—most of them young conscripts and none of them dedicated Nazis—were being bussed out daily to work on regional farms to help alleviate the farmhand shortage. At one place, a farmer asked if he could feed the POWs hot dogs for lunch. When told yes, this person did so, and afterwards, the grateful POWs worked twice as hard. When the Army’s Inspector General made what the POWs were doing public, the locals stopped grumbling.

Today, one of the CCC buildings houses an exhibit about military history, and the other is dedicated to local natural history. The latter contains furs, a bison rug, and several stuffed specimens that have seen better days. There is also an egg collection gathered by Charles E. Slocum for whom the museum is named. He was an early settler in the county. Probably the best-preserved specimen here is a passenger pigeon, possibly because it’s inside a thick glass display case that keeps the elements and touching tourists away. Passenger pigeons, said to be so numerous they darkened the skies for days at a time, were hunted to extinction, in part because they made for good eating.

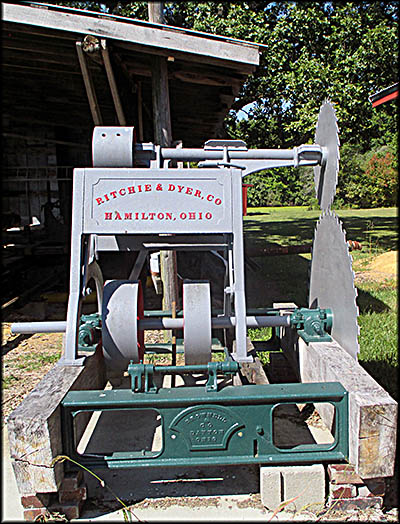

They lived in the Great Black Swamp, but were likely scarce at the beginning of the twentieth century due to habitat loss. In those areas not cleared for farmland, lumbering decimated what was left of the swamp’s trees. The museum has a working sawmill with a restored saw to demonstrate how the process worked. When farmers went out into the forest or woods to cut down trees for the mill, they transported them in a sawmill shanty. The museum has one of these that was built in Highland Township in the late 1800’s. Originally used by John Hale, it passed through three more generations before being donated to AuGlaize Village.

In addition to running a sawmill, the museum also makes cider, apple butter, and molasses each year. To make the last, they grow sorghum in a garden, a plant that looks similar to cornstalks at first glance. Farmers started growing sorghum in the late 1850s hoping that it would serve as a substitute for sugar, which was quite expensive at that time. You couldn’t make decent sugar from sorghum, but it did produce excellent molasses, which was an alternative sweetener. Production of molasses in Defiance County peaked in the 1860s, then declined.

They lived in the Great Black Swamp, but were likely scarce at the beginning of the twentieth century due to habitat loss. In those areas not cleared for farmland, lumbering decimated what was left of the swamp’s trees. The museum has a working sawmill with a restored saw to demonstrate how the process worked. When farmers went out into the forest or woods to cut down trees for the mill, they transported them in a sawmill shanty. The museum has one of these that was built in Highland Township in the late 1800’s. Originally used by John Hale, it passed through three more generations before being donated to AuGlaize Village.

In addition to running a sawmill, the museum also makes cider, apple butter, and molasses each year. To make the last, they grow sorghum in a garden, a plant that looks similar to cornstalks at first glance. Farmers started growing sorghum in the late 1850s hoping that it would serve as a substitute for sugar, which was quite expensive at that time. You couldn’t make decent sugar from sorghum, but it did produce excellent molasses, which was an alternative sweetener. Production of molasses in Defiance County peaked in the 1860s, then declined.

To make molasses from sorghum, one cuts the tops of the plants off, strips the leaves, and runs what remains through a press. The press that the museum uses was originally purchased in 1875 by Wenzel Zimmerman, and it passed through several generations before being donated the museum in 1966. After being pressed, the resulting juice is placed into the museum’s evaporator where it’s cooked for two to four hours. When done, it’s strained.

At the Justin Coressel Farm Museum One I learned something about which I was unaware: at one point in time, farmers grew tobacco in Defiance County! Varieties included Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky and Spanish Broadleaf as well as Little Dutch. The growing season began in a hothouse where seeds were planted about forty inches apart. These were transferred to fields when the weather became consistently warm. This tobacco was harvested before the first major frost, dried, then packaged up and sold.

The last place we visited was the red barn, the one that came with the property when it was given to the Defiance Historical Society. It’s filled with a hodgepodge of historic artifacts, mostly to do with farming, but it also contains replicas of defunct places of business from the county. One is the office of dentist Emery Blosser. Although born in Williams County in June 1878, he was raised in Defiance County. After graduating from Cincinnati’s Ohio College of Dental Surgery in 1903, he set up a practice in Edgerton, Williams County. He retired shortly before passing away in December 1967.🕜

At the Justin Coressel Farm Museum One I learned something about which I was unaware: at one point in time, farmers grew tobacco in Defiance County! Varieties included Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky and Spanish Broadleaf as well as Little Dutch. The growing season began in a hothouse where seeds were planted about forty inches apart. These were transferred to fields when the weather became consistently warm. This tobacco was harvested before the first major frost, dried, then packaged up and sold.

The last place we visited was the red barn, the one that came with the property when it was given to the Defiance Historical Society. It’s filled with a hodgepodge of historic artifacts, mostly to do with farming, but it also contains replicas of defunct places of business from the county. One is the office of dentist Emery Blosser. Although born in Williams County in June 1878, he was raised in Defiance County. After graduating from Cincinnati’s Ohio College of Dental Surgery in 1903, he set up a practice in Edgerton, Williams County. He retired shortly before passing away in December 1967.🕜

You enter the museum grounds through the visitor center.

Great Black Swamp Exhibit

The red barn came with the land when the Defiance Historical Society acquired it for the AuGlaize Village & Farm Museum.

Sherry School

These pulleys are designed to give visiting schoolchildren something to get their hands on.

St. John Lutheran Church

This organ was purchased by St. John Lutheran Church in 1892.

This signal was used by the Jewell Depot to let passing trains know whether or not they needed to stop to pick up a passenger.

This steam engine is being sent to a museum in Indiana.

Post Office from Mark Center

Calander from Doctor Robert B. Cameron's Office from the town of Jewell.

Ayersville Telephone Company's Building

These buildings were used by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) during the Great Depression, and later made into mess halls for German POWs held in Defiance.

Sawmill Shanty

Sorghum Garden

Sorghum Press

Kinner Cabin

Restored Ritchie & Dyer Co.'s Saw